Are we really still making body-shaming ads in 2021?

Melissa Chapman, Co-Chief Executive Officer at Jungle Creations, says that while steps have been taken to avoid overt body shaming adverts, the industry is still guilty of a subtle, pernicious attack on women's - and men's - insecurities.

Scrolling through your social platform of choice, it is easy to miss the sexism among a sea of snackable content. It’s not as overt as it once was. No, this is more subtle, though no less pernicious.

Women have long been subjected to ad campaigns about pleasing their husbands, looking after kids and keeping in 'good shape'. Women have long been plastered across billboards with the aim of sexualising everything from cars and beer, to air conditioning units. And we’ve long been shamed into feeling like we should be unhappy with our appearance, whether that’s through overt body shaming or more covert beauty filters and air brushing.

We’ve long been shamed into feeling like we should be unhappy with our appearance.

Ever since the Advertising Standards Authority banned ‘harmful gender stereotypes in advertising’ a couple of years back, very rarely today do laddish, offensive, objectifying brand comms make it out the door. Those that do are soon torn to shreds.

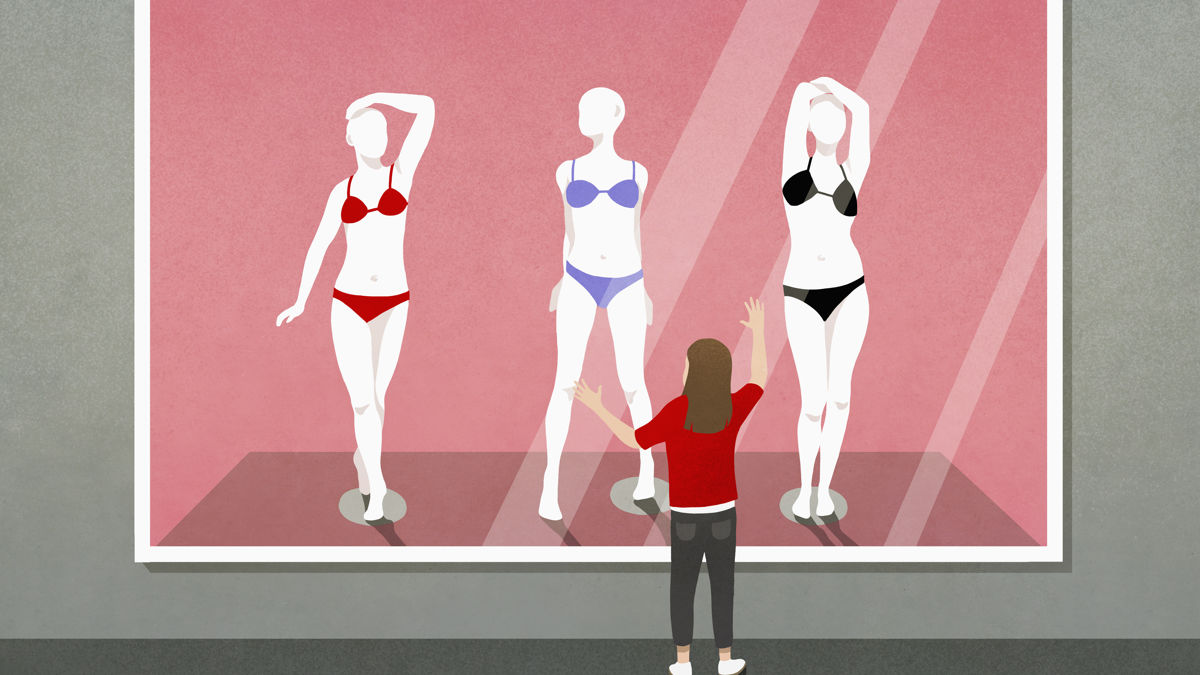

Above: An ad from 2015 which caused controversy after being accused of body shaming.

This is clearly good news. But it seems that demoralising women is a hard habit to kick for an industry still overwhelmingly male. While the worst has been all but eradicated, in its place has come a torrent of brand-led body-shaming hidden behind influencers and digitally enhanced bodies. It is a constant drip-feed of weight-loss teas and meal replacement shakes.

It feels, at times, as if exploiting women’s insecurities worked so well for so long that there are some creatives who have yet to come up with any better ideas.

There is a pressure applied to women that simply isn’t applied to men to the same degree with regards to our bodies and health. We’re constantly being told to eat less, exercise more, be less hairy, stop ageing, wear make-up and obtain an unrealistic standard of Western beauty, even if it kills us.

It feels, at times, as if exploiting women’s insecurities worked so well for so long that there are some creatives who have yet to come up with any better ideas. Making women feel bad about themselves, or intimating that they must present themselves in a way that is sexually appealing, is an approach that clearly drives sales. But that doesn’t make it right, it doesn’t sit well with consumers and, moreover, consumers are becoming wise to it. No longer are women sitting back and letting this damaging messaging insidiously weave into their subconscious, women are taking a stand and calling brands out for feeding their insecurities that are so often only there in the first place because of advertising.

Above: Brands such as Fenty have embraced a more inclusive, body positive approach to their products and advertising.

This sort of brand messaging is never more prevalent than during the New Year period. Every year we are told to reinvent ourselves. 'New Year, New Me' seems innocuous enough; many people make resolutions, after all, but many people do not, and pressuring them to do so causes unintended but very real harm.

We spent January raising awareness of this phenomenon through Four Nine’s New Year’s Revolution campaign. It encourages brands to take the pressure off following a year of Covid conditions and an acute rise in mental health problems. People already feel terrible, so why would you make them feel worse? With YouGov we carried out a 2,000 person survey to better understand how the public feel about this sort of targeting and messaging. A huge majority (70%) of both men and women feel as if women are targeted more often in weight loss adverts and messages.

The gender imbalance in messaging is designed to capitalise on women's perceived higher levels of insecurity surrounding their weight.

This doesn’t reflect the reality of obesity and associated ill-health in the UK. According to The Health Survey for England 2017, men are more likely than women to be overweight or obese. I think you could safely assess that the gender imbalance in messaging is designed to capitalise on women's perceived higher levels of insecurity surrounding their weight, rather than factual health reasons.

While the ASA banned ‘harmful gender stereotypes in advertising’, which goes some way to reducing sexist stereotyping in advertising, this still leaves plenty of room for exploiting gendered expectations of women. Interestingly, however, the ASA has just recently banned ‘misleading’ beauty ads – those which use filters and editing to make a product look better than it actually is, which helps to fill the void that the former ruling left.

Above: Four Nine, the 'female first community', launched a New Year's Revolution campaign encouraging body positivity.

However, I still don’t think these rulings go far enough. I would go one further and ban ads that promote unrealistic beauty standards altogether, especially those which overtly - or covertly - body shame. Of course, an outright ban is unlikely any time soon, and would be difficult to implement, let alone manage. Beauty is, after all, subjective, but our research shows there might be support for it. Around 46% of women want to see more of a focus on body positivity and self-acceptance in media and advertising than they presently see, a notion echoed by 27% of men.

If not a ban then a challenge to others in our industry: stop it. One only has to look at the success of Monki, Fenty and many more to see what difference body positivity and inclusivity can make. Brands have an opportunity to support women and capitalise on their growing confidence, yet still so many continue to try and exploit their insecurities instead.

Making women – or men, for that matter – feel guilty about their appearance feels like the dying breath of the old world of advertising.

Making women – or men, for that matter – feel guilty about their appearance feels like the dying breath of the old world of advertising. Making people feel good about the body they are in is far more effective than shaming them into submission. Not everyone is in a position – either physically or mentally – to make the changes to their life advertising pressures them to make. Indeed, not everyone wants to make changes. It may surprise brands that some people are perfectly happy as they are. Pressuring people to change when they can’t or don’t want to can be soul-crushing. So stop it.

)

+ membership

+ membership