Does gaming have a future in high street stores?

As "the beating heart of the entertainment industry", video games are huge business. But, as players gravitate further away from physical products, what happens to the high street stores that have fed gamers' habits until now? Marta Swannie, Creative Partner at Design Bridge and Partners, thinks store evolution is needed.

People like to play games. This isn’t news. As long as we have been walking and talking (and perhaps even before), we have been playing games.

In the Persian Gulf, archeologists discovered the oldest game in the world; 'The royal game of Ur', which was invented by the Assyrians more than 5,000 years ago. So, true to our nature, it’s no surprise that the age of the computer was immediately followed by the age of the computer game.

Future archeologists will be able to track the dramatic growth of digital games.

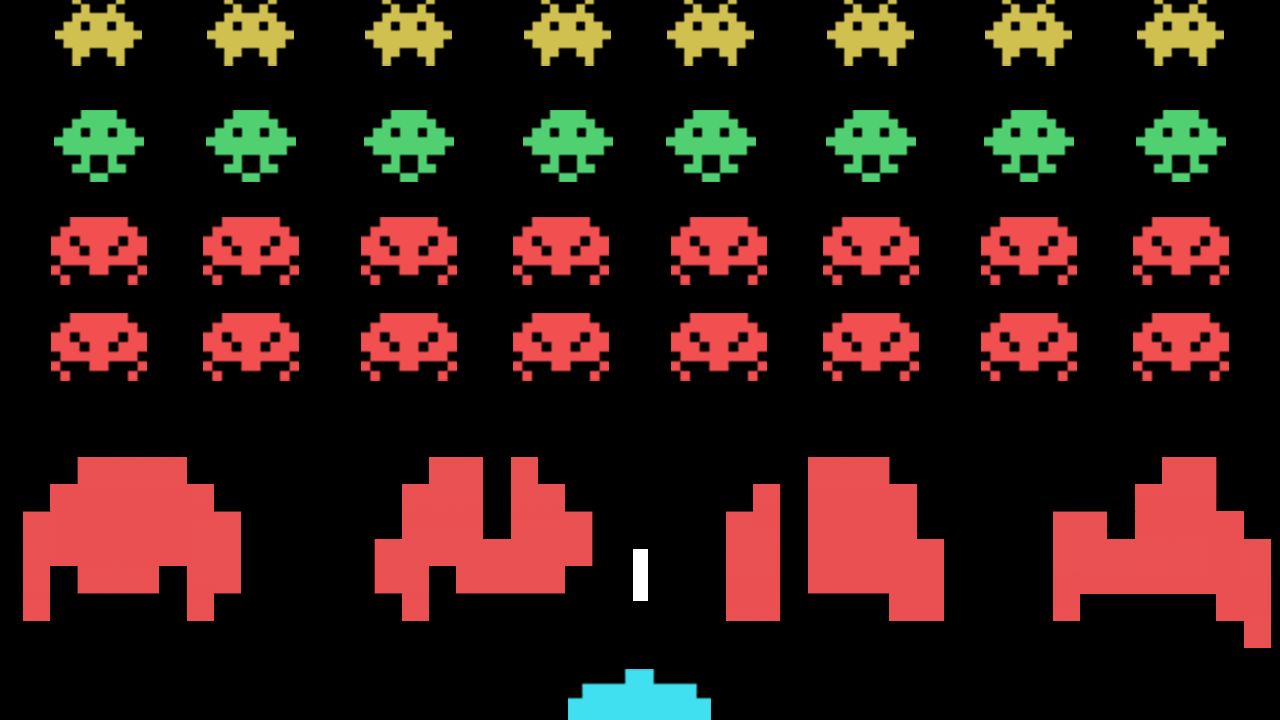

Future archeologists will be able to track the dramatic growth of digital games. They could stumble across remnants of the gigantic computers which powered William Higinbotham’s 1958 Tennis for Two, or vast graveyards of classic games arcades dedicated to Space Invaders or Pong.

Above: People like to play game, from the current Call of Duty franchise, back to Space Invaders and beyond.

The video game industry is massive. It’s bigger than the music and film industries combined. In fact, gaming is now the beating heart of the entertainment industry at large. Driving the digital revolution and dictating consumer behaviours and preferences. But while those future archeologists will dig up countless consoles and controllers, after a certain point, they will stop digging up games. Or at least their physical copies.

Is this the end of the physical era for video games?

Popular highstreet chain Game recently announced it is phasing out the sale of pre-owned games. Physical sales have been declining sharply over the past decade, with most consumers opting to buy and download digital copies. For example, Sony announced that physical game sales represented just 4% of PlayStation revenue last quarter. Most PCs and consoles now make the disc reader an entirely optional addition or simply don’t support hard copies, just like users of the digital-only PS5.

Copies of games aren’t the only thing on the chopping block. The physical console itself is increasingly becoming obsolete with gaming heavyweights including the likes of Xbox, giving users access to their extensive libraries of video games via the cloud.

So, is this the end of the physical era for video games? And, if we don’t need copies or consoles, do we need stores?

Above: Physical stores need to evolve to become locations for brand-building as much as point-of-sale.

Changing places

The reasons for gamers to visit game stores are dwindling, but that isn’t to say people aren’t keen on going to places. Digital technology is replacing the real world, but is it changing what we want from it?

Across markets and sectors, people are choosing experiences over products. Retail spaces are evolving in line with this consumer demand and stores are acting less like points of sale, instead becoming pivotal brand-building locations. They are a chance for consumers to get hands on, places at which to share experiences with old friends, or for common passions to forge new bonds.

Across markets and sectors, people are choosing experiences over products.

These are 'third spaces', essential for giving people - and their passions - a sense of place, particularly in a world where the line between work and home is increasingly blurred. Games retailers aren’t the only physical retail space feeling squeezed between these forces. Blockbuster was the first high profile brand to fall as consumers moved from physical to digital entertainment channels. But as the landscape shifts, new opportunities emerge.

Camp in the US, for example, doesn’t describe itself as a toy store. It defines itself as a 'family experience company'. It is all about creating immersive, interactive, physical and digital play areas in store. They are not competing with e-commerce retailers, they are competing with any venue that families go to spend time together.

So, can games stores do the same?

Above: Blockbuster was the first big high street casualty of the move to digital entertainment, but it might not be the last.

Slow business vs show business

Games retailers aren’t in the business of selling games, they’re in entertainment. So, to survive, they are going to have to become entertaining.

Stores like Game need people to come through the door, so they need to offer something they can’t get in any other space. Can stores become themed around specific interests? Could the FPS section have a VR shooting range? Or contain Airsoft replicas of popular guns on Call of Duty? Could racing sections look more like arcades of old, with high-tech gaming rigs set up for friends to compete?

People are always going to play games. The only difference is, now, they don’t need stores.

These experiences can open the doors for more diverse audiences to engage with physical spaces. The demographics of gamers are changing. It’s no longer a club for teenage boys, and this needs to be reflected in the shape and feel of a store.

If you doubt the appetite of gamers to turn up in person, look at the meteoric rise of esports, which is flooding streams and filling arenas. Or examine the convention phenomenon, with individual events, such as Gamescom drawing over 320,000 in-person attendees. Game stores could become an always-on convention venue in every town and city.

Enter player three

It doesn’t matter if you are in ancient Persia or modern Piccadilly. People are always going to play games. The only difference is, now, they don’t need stores.

Games stores need to think less like retailers and more like entertainment companies. There is the opportunity to create meaningful, longer-lasting bonds with customers, forging communities through shared experiences in third spaces.

)

+ membership

+ membership