Does Sora mark the end for directing as we know it?

With OpenAI's new text-to-video software leaving slack-jaws around the industry, The Moon Unit speculates if we're looking at a new chapter in filmmaking.

Sora has landed. Releasing 33 incredibly realistic preview films over the last few days, the brand new text-to-video software by OpenAI – makers of ChatGPT – has blown the internet’s mind.

Why? Because of the quality of its videos, which is quite simply insane.

For now, a Sora film may still feature errors, such as human fingers swapping places, items of furniture randomly levitating, or a biscuit that gets bitten and is magically whole again afterwards.

But it’s a quantum leap from where text-to-video was just a few weeks ago.

Credits

powered by

Above: OpenAI's Sora demonstration, including AI-generated golden retrievers. Puppies of the apocalypse, as far as directors are concerned?

The Sora software can currently only create videos up to 60 seconds long, (perfect for the TV commercial market) and it isn’t currently available to the public. But no doubt it soon will be.

This obviously raises concerns about the risks of deepfakes being used to spread misinformation during the upcoming US election.

From a societal point of view, we simply have to hope that OpenAI will be able to effectively police its invention – it already has policies in place to prevent Sora from depicting extreme violence, sexual content, imagery of hate, and anything resembling real celebrities or politicians.

Once this technology closes that final 10% gap between its current quality, occasional uncanny valley moments and true cinematic video, it’s surely game over for directors.

But… for our industry, the question that immediately springs to mind is… is this the end?

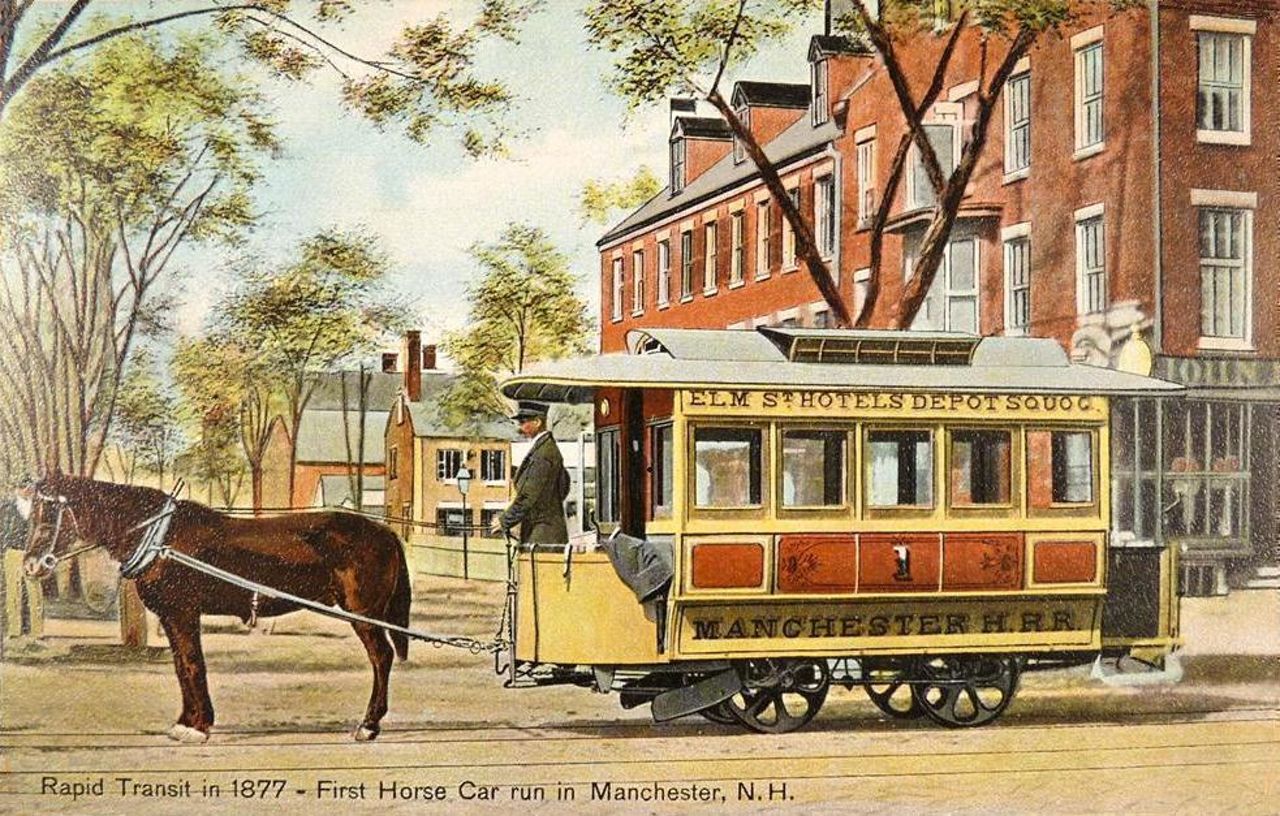

If you’re a director reading this, should you be as worried as a blacksmith reading a newspaper article about the invention of motor cars?

Above: Change can come quickly. In 1900, 6000 horses were employed hauling trolley-cars in New York alone. By 1902, 97% of America’s streetcars were running on electricity.

Wired conceded that Sora’s preview clips were “impressive” but added that “it will be a very long time, if ever, before text-to-video threatens actual filmmaking.”

We don’t agree. It’s reminiscent of the famous quote by IBM Chairman Thomas Watson who said in 1943 that “… there is a world market for maybe five computers.” Or Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer’s 2007 prediction that “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share.”

Jeffery Katzenberg also disagrees. He told the Hollywood Reporter that he thinks generative AI will eliminate 90% of jobs in the animation industry. And that was before Sora.

Once this technology closes that final 10% gap between its current quality, occasional uncanny valley moments and true cinematic video, it’s surely game over for directors.

Why? Ad agency creatives will be able to simply upload their scripts to Sora, which will spit out the finished ad. Multiple iterations of it, tweaked to client remits and audience research.

Likewise, once Sora expands beyond a sixty-second time-length, movie screenwriters can feed their screenplays into Sora and then submit the finished film to producers, without the need to go via a director. Once AI voice technology advances to a level where it can perfectly replicate human speech patterns, actors too are finito. And what happens to all the hierarchies of people that make up the film industry today?

So directors, on the face of it, are on the brink of extinction. Or are they?

Once upon a time, only people who could paint (or sculpt) were considered artists.

There’s another way of looking at this. The future for directors may not be death, but democratisation.

Once upon a time, only people who could paint (or sculpt) were considered artists. But the introduction of new technology, such as video and Photoshop, was part of a revolution that made art-creation more accessible. Today, being an artist is not necessarily about the quality of your drawing, but your thinking.

Similarly, there was a time when in order to be a musician, you had to play an instrument. This has now changed. Although there were always exceptions to the musicianship rule – Sid Vicious of The Sex Pistols reportedly didn’t know how to tune his bass, let alone play it – it was new technology that really opened up the field.

It seems unlikely that David Guetta and Calvin Harris could be called ‘musicians’ in the traditional sense of the word, yet here we are.

This clip of DJ Khaled trying to play a guitar tells you all you need to know. Being a musician today has nothing to do with skill at musical instruments. Instead it’s about your taste, your creativity, and your ability to get other people to buy into your ideas.

Couldn’t that become the case for directors?

Above: DJ Khaled - a man who can’t play any musical instruments who technology assisted to become one of the world’s most popular musicians.

If this analogy holds true, there will still be directors. In fact there could be more of them than there are right now. But the definition of who gets called a ‘director’ will inevitably broaden.

A director won’t be someone who’s able to master the skills of lighting, camera movement, and getting great performances out of actors. Instead, a director will be anyone who has the vision and ambition to bring ideas to life in a way that’s never been seen before. They won’t need a film degree. They won’t need a production company. They may not even need a runner to bring them coffee.

A director won’t be someone who’s able to master the skills of lighting, camera movement, and getting great performances out of actors.

But they’ll still exist – in more varied and interesting forms, perhaps.

According to the New York Times, the team that developed Sora named it after the Japanese word for sky, to signify its “limitless creative potential.”

So once we get over the shock of it, maybe that is how we in the production world should view it.

Not as the end of something.

But the beginning.

)