How advertising falls into fight, flight or freeze... and what to do about it

Faced with fear, humans generally have three responses; run and hide, play dead, or come out swinging. But those responses evolved from a time when danger was almost always life threatening. So, how do they relate to today's fears? The Moon Unit reevaluates our fight, flight and freeze responses for a modern world.

When humans become afraid our reaction is either fight, flight or freeze. It’s been programmed into us over thousands of years of evolution.

When we were facing a threat like a sabre-toothed tiger we prepared to either fight it, run away, or play dead in the hope it lost interest. But how does this apply to advertising? And how can we use it to our advantage?

When humans become afraid our reaction is either fight, flight or freeze.

The most useful application is getting the best out of people we work with by identifying when they’re feeling fearful. Also, to identify the times when we ourselves are fearful, but didn’t realise because, once we understand someone’s true driver (or our own), we can address it.

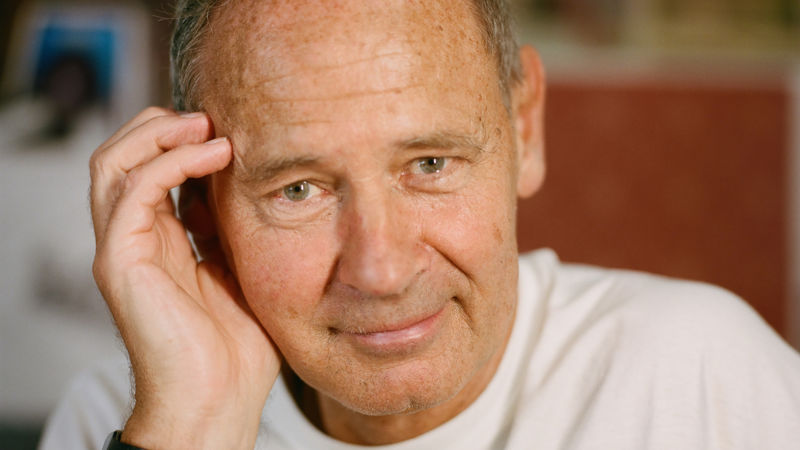

Above: Christian Bale [above left] went ballistic on the set of Terminator Salvation, launching a tirade against the DoP that included 36 F-bombs. But could his ‘fighting’ reaction have been motivated by fear, perhaps that the movie wasn’t very good?

Let’s take ‘fight’ first. Lots of fights take place in advertising. Marketers fight with their agencies, creatives fight with directors, directors fight with producers. It’s a long list. Our normal reaction is to interpret a fight as being caused by disagreement. We think ‘this person has a different point of view to me, they’re not happy with the way things are going, and they want to change course'. We then either try to talk them around, or we back off, depending on whether we think we can win the argument or not, and how much it will cost us to do so. But this approach may be misguided.

Marketers fight with their agencies, creatives fight with directors, directors fight with producers.

According to the principle of fight, flight or freeze, the person may be fighting with us because they are afraid. To have such a strong reaction, they must be afraid what we’re doing will compromise their safety in some way, which (in a business context) means their income. They worry we’re going to cost them money, or threaten their career, perhaps by getting them into trouble with someone who pays them. The implication is we may be better off trying to reassure them than argue with them. If we can reduce their fear, their desire to fight should dissipate.

Above: Running away is a classic safety-seeking behaviour.

Now let’s look at ‘flight’. We’ve all experienced colleagues or clients who have suddenly gone AWOL. What the hell?! They were supposed to be at this meeting and they’ve disappeared, and now we can’t get hold of them. They’re not answering their phone, and they’re not returning texts or emails.

Our natural assumption is they’re either angry with us, or feeling hurt or depressed. But this may be incorrect. They may, in fact, be afraid, since running away is a classic safety-seeking behaviour. Now that we know we’re dealing with fear, we have a better chance to address it. Once again, rather than getting cross with them, or arguing with them (‘but you said you’d do this call!’) we might be better off reassuring them.

The ‘freeze’ reaction is the least well-understood. How on earth can it benefit someone to seize up?

The ‘freeze’ reaction is the least well-understood. How on earth can it benefit someone to seize up? And yet, we see it all the time. Perhaps the most common expression of ‘freeze’ is procrastination. A director, faced with the need to write a treatment, spends the first two days after the briefing doing anything but that. Creatives play pool or ping-pong rather than working on their scripts. Even producers – those paragons of productivity – have been known to procrastinate when they know they really shouldn’t.

Again, our reaction in these situations may be wrong. We have a tendency to view a person who is procrastinating as either lazy or useless. But, in reality, they may be afraid. It could be they fear they will fail, or that the project will be painful. As before, if you are faced with someone who is procrastinating, rather than trying to cajole or encourage them, you may be better served to work out what they’re afraid of, and address that.

Above: We have a tendency to assume those who are procrastinating are lazy, but they may just be afraid.

But, even more valuable than the ability to identify fear in others, is the ability to identify it in ourselves. We don’t like to admit we’re fearful. Partly that’s because we don’t like to acknowledge such an uncomfortable emotion, and partly it’s because we don’t understand how a Zoom call – a Zoom call about a commercial, for Christ’s sake – could be causing a response as primal as fear.

And yet it can. Anything that threatens our survival causes fear. And, as we’ve seen, a threat to our income is a threat to our survival since it causes an unconscious anxiety that we may end up with insufficient money for food and shelter.

We don’t like to admit we’re fearful. Partly that’s because we don’t like to acknowledge such an uncomfortable emotion.

In an advertising context, many situations can threaten our income. For example, a disagreement means we could get fired from a job. Or making a bad commercial could mean we find it difficult to get other jobs in the future. It’s always worth observing our own behaviour. If we find ourselves arguing without thinking, running away from the situation, or procrastinating it may be that we have gone into fight, flight or freeze. It may be that, without realising it, we are afraid.

The solution? Admit that we’re afraid, work out what it is we’re afraid of, and face up to it. When we do that, our self-sabotaging behaviour can cease.

)

+ membership

+ membership