How African mythology inspired a Queer metamorphasis

An entrancing visual journey intertwined with Black Queerness and African spirituality, Justice Jamal Jones' Notes on a Siren offers a thought-provoking narrative on transformation. shots caught up with the director to uncover the connection between mermaids, mirrors, and modular synthesisers.

Helmed by Justice Jamal Jones through Valiant Pictures, this groundbreaking and gorgeously-crafted short film, titled Notes On A Siren, explores - from Jones' own perspective - the archetypes of modern Black Queerness and Transness in film.

Through visceral choreography and sublime, organic visuals juxtaposed with archival film footage and jarring mechanical imagery, the collaborative creative reconsiders both ancient and modern myths of mermaids from a contemporary perspective in three clearly-defined acts.

In particular La Sirène, a mermaid from Haitian Vodou, becomes a vessel through which Jones re-examines their own role as a director and their relationship with the camera as a Black Trans Femme, serving both a source of empowerment and self-critique.

Inspired in part by the Caymans Islands’ hotel Palm Heights, Jones encountered many artists who helped inspire and influence the film, including musical artist Raheaven, whose experimental pop and R&B music was incorporated into the film's soundtrack.

Credits

powered by

-

- Production Company Valiant Pictures

- Director Justice Jamal Jones

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Valiant Pictures

- Director Justice Jamal Jones

- Executive Producer Matthew D'Amato

- Executive Producer Vincent Lin

- Producer Justine Sweetman

- DP Corey Hess

- Sound Engineer Alvaro Herrasti

- Editor Conner Reddan

- Composer Zach Beebe

- Music Producer Raheaven

- Sound Designer/Composer Joseph Magee

- Colorist Calvin Bellas

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Valiant Pictures

- Director Justice Jamal Jones

- Executive Producer Matthew D'Amato

- Executive Producer Vincent Lin

- Producer Justine Sweetman

- DP Corey Hess

- Sound Engineer Alvaro Herrasti

- Editor Conner Reddan

- Composer Zach Beebe

- Music Producer Raheaven

- Sound Designer/Composer Joseph Magee

- Colorist Calvin Bellas

How did Notes On A Siren evolve from its conception to the final creation? How did introducing other creatives affect its direction?

The idea for Notes on a Siren came to me through spiritual work and getting more connected to my ancestry and their religious and spiritual connections. I have always been fascinated by mermaids; being a young queer kid, mermaids are intrinsically queer--they’re in-between, they don’t fit in, etc. I felt connected to them. But then I started to look at stories of mermaids and sirens and see their stories reflected in my own life. Sometimes I felt like the sailor as a filmmaker, on a crusade and capturing subjects on my own “voyage”; sometimes like the siren, a mystical being captured as a muse. The film started with those pieces.

You often feel like you’re in between two worlds. Even the original The Little Mermaid story was written from a queer perspective.

Adding other creatives impacted the direction a lot. Connecting with Valiant Pictures’ Matthew D’Amato was huge. We’re in sync when it comes to creating mystical work with a deeper meaning. In talking with him I discovered places I didn’t think we could push the film. The Siren in a lot of ways is a group creation; even though I’m taking its form, she was a group effort. In a way, she’s a cyborg. Sound Designer Joseph Magee made her voice, Cory Hess was the Cinematographer who figured out how she would be seen on the camera, and choreographer Imani Fuentes figured out how she would move. It’s a group project that I have the honour of being able to slip into.

Having worked commercially for the past year, how did you find the experience of taking on a film with complete creative freedom?

Strangely it didn’t feel much different. With film, you’re always negotiating and never have total creative freedom. I’m okay with that. Notes on a Siren taught me that you work with other people and consider what they want and suggest, too. So it didn’t feel so different. But, I was able to explore themes that pushed beyond the commercial.

What drew you to the myth of the Siren as a vessel for exploring Black Queerness and Trans identity on camera? Is mythology something you’d like to explore further in your filmmaking?

Mythology is definitely something I want to explore further. What drew me to the siren and mermaid was also that it felt like the year of the siren. Prior to that, you had Halle Bailey as The Little Mermaid and its subsequent tension. But when you look back to African mythology, there are mermaids all the time in the form of Yemaya ,Oshun and La Sirène--there are many mermaid-like entities. I found the pushback ironic, as it’s not new. For Black, queer, and Trans identity, it’s about being in-between.

I told my team that they might have specific roles on set, but they’re dynamic humans and don’t have to be stuck in these stereotypes.

You often feel like you’re in between two worlds. Even the original The Little Mermaid story was written from a queer perspective. Hans Christian Andersen was in love with one of his colleagues and felt separated from being with him. The Little Mermaid offers a middle ground that I wanted to celebrate, including the imperfection of that middle ground. In the film, we see water and technology a lot, which usually don’t correlate. I wanted to show them hitting up against each other.

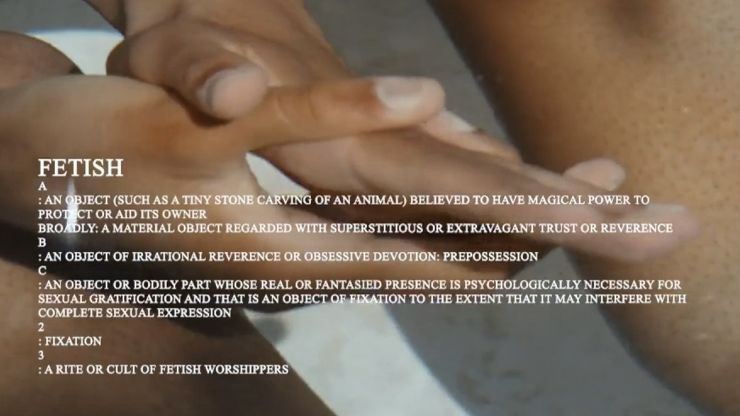

Can you elaborate on how the film allowed you to ‘transcend my feared roles associated with the camera from fetishised subject to bitchy director, and rethink my relationship to the camera’?

I often feel like I’m in very concrete roles on set sometimes. As a POC, I feel like I have to prove I’m in the director role. It’s also a different thing; me being a director is different from a cis man being a director, because I don’t bring that patriarchy with me. At first, I thought I needed to be domineering or controlling to be taken seriously. But then I realised I have another part of me that is an asset and a gift, which comes from my femininity and ability to shape-shift and connect with people in different ways.

You get three different people out of the project: a subdued version, then me being a director, a moulting/shedding/morphing version, and then a final version that’s no longer me.

I like creating sets that allow others to be all they can be. Doing that made me realise I can be all I want to be: the director, the subject, etc. That all started by creating that blueprint for everyone. I told my team that they might have specific roles on set, but they’re dynamic humans and don’t have to be stuck in these stereotypes.

The film is divided into different parts. Can you tell us more about the significance of each part and why you chose to arrange it like this?

The film has this dream quality where it’s very detached from time and continuity. I realised when watching it without the parts that there was a better way to section the film and help people understand what they should be looking for in each part. Without the parts, it gets a little trippy. At each marker, viewers can recollect themselves and mentally prepare to re-enter a new space.

Film can serve as a colonial and propaganda tool; film by default always projects something onto us.

I also realised that the parts almost feel like there are three mini-movies in the project. We have this thesis/doc-like intro, then a music video with the fetish song, and then the “final form” with the siren; all of the sections are there to show the transformation. You get three different people out of the project: a subdued version, then me being a director, a moulting/shedding/morphing version, and then a final version that’s no longer me.

Can you tell us more about your creative decision to weave archival film footage into the story?

The archival footage was really important; I just really wanted to talk about the history of film. I’m amazed by film because it’s new; existing for 100 years-ish still makes it a new medium. When it entered our society it was very interesting, as it was during a time when only a certain demographic of people had access to the art.

Film can serve as a colonial and propaganda tool; film by default always projects something onto us. Early 1940s films and documentaries talked about spirituality, islands and tribes in untouched places, and linked those communities to savagery, evil, and devil worship. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think it’s a reflection of not just the time, but also how powerful film as a medium was.

We’re always shifting and remaking ourselves, and I think that’s one of the most beautiful things about life.

Film at the beginning of its art form was already projecting these ideas into the world, almost making its own genres. We have a “zombie” genre now--and that’s from a Haitian Vodou word! We have a genre based on something that happens within someone else’s religion that has been so warped that it has become something new entirely.

Weirdly, there is a filmmaker in the found footage in the beginning of the film who follows me every step of the way, and he changes the way I change. At the beginning, he wants to write his own story, and by the end, he is corrupted by Vodou people. I wanted to subvert that narrative and remind viewers they have entered my world by that point.

There’s an interesting contrast running through the film between lots of pure, organic visuals, and technology and electronic imagery. What was the reasoning behind this?

I think of Vodou as a kind of lost African technology that has to do with nature, spirit, and the soul. There were things like vèvès, which are portals for spirits to come through. I felt like spirituality was the middle ground of these two spaces, the very natural and very tech-centred.

Technology queers the natural a lot, and conversely, I think nature also queers technology.

I’m also obsessed with the question of what is natural and what is medicated, which is a trans conversation now. Tech, in a strange way, creates identity in today’s society. We’re in a world where we’re asking whether some procedures are or are not natural. And sometimes, things that feel natural actually aren’t, but we allow those to remain and be “okay.” Technology queers the natural a lot, and conversely, I think nature also queers technology.

In the film, the modular synthesiser is used as a communication machine in a weird way. These synthesisers (from what I understand) pick notes randomly, and in so doing reflect how naturally random our world is. The machine aligns to the natural mathematics of chance in our world, but does so with technology. I found that beautiful, where getting a feeling from music made just by chords and a machine is still “real.” The siren is that too; the siren metaphorically and in real life is a cyborg. She lives mostly within these technological spaces.

Although it was a very personal film in many ways, what do you hope people might take away from it?

I hope they take away that they too have the ability to change and transform, and that we’re always doing so. We’re always shifting and remaking ourselves, and I think that’s one of the most beautiful things about life. We’re in this continuous death and rebirth cycle; just embrace it.

)