How Renee Maria Osubu framed fatherhood in Philly

A young Black photographer-turned-filmmaker, Renee Maria Osubu, represented by the new talent powerhouse You Are Here, talks about her directorial debut, Dear Philadelphia, a self-reflective film of fatherhood, forgiveness, and finding the spirit of faith in the people of Philadelphia.

When Renee Maria Osubu talks about Philly, you feel it. Philadelphia, she explains, is universal.

It’s an American city, through and through, and you can’t just put Philadelphia anywhere. It wouldn’t work in England, where Osubu is based, it only works in Pennsylvania, nestled in between the Rust Belt and New York City. Philly is memorable, it’s a city that is foundational to America, that has never stopped being a foundation for political action and movements.

But it’s also a city full of relatability. It’s a city, Osubu says, that is full of love.

Osubu was born and raised in London to Nigerian immigrants, and she’s never strayed far from her roots. Her faith and her family ground her, and inspire her work. She actually first visited Philadelphia through a faith-based summer program, Camp Hope for Kids. As a photographer, she volunteered her skills and expertise, guiding inner-city kids through their first rolls of film, giving them disposable cameras, and telling them to go home and find something worth sharing.

Relatability was important; Osubu had to make these hyper-local stories engaging for a universal audience.

When she saw the work they came back with, she had to see this city for herself. That’s all it took for her to start a six-year artistic affair with an All-American City, visiting every year to continue her work as a counselor and then, later on, as an independent photographer. Her relationships with the kids drove her to become a part of the community, to know and understand a city that became a second home for her.

A formally trained photographer, Osubu has always focused on highlighting minority communities. Much of her photography dealt with difficult moments, with things about a people or a culture that outsiders would call dehumanizing or shameful. For Osubu, in order to create intersectional artwork, she had to turn her lens on what other people might not consider worth capturing. Going against this instinct look away in order to focus on the struggles of race, gender, and class in Philadelphia gives Osubu’s work authenticity without compromising her vision.

“Around the time I made the film,” she says, “I lost my father.”

The impetus to move from still photography to film came from five years spent in the community. After displaying these photos over half a decade, Osubu recalls that “a lot of people in the UK were drawn to this work, and while I knew the stories behind all the photographs, they didn’t.”

“I could show potential subjects the photographs I had already taken. People would flip through and say, ‘that’s my cousin!’ and be more willing to work with me.”

Dear Philadelphia was meant to tell those stories. It seemed like while photography might only show some of the picture, a film about the lives and struggles of a community would help viewers understand what they were looking at, beyond the striking photos. “Their stories,” Osubu says, “moved beyond photographs.”

Journeying into Philadelphia again, Osubu was worried that people might not be as welcoming of a camera crew as they would be of a single photographer, but she quickly found that her five years photographing the residents helped ease the transition. “I could show potential subjects the photographs I had already taken. People would flip through and say, ‘that’s my cousin!’ and be more willing to work with me.” After that, it was friendly, an exchange, a conversation. “They wanted to talk. They wanted their stories to be out there. Whenever I describe the project I frame it as an archive of all these amazing people.”

For Osubu, in order to create intersectional artwork, she had to turn her lens on what other people might not consider worth capturing.

Osubu admits that this was her first experience working with film. I asked what the biggest challenge was, and she’s game enough to reply that changing the way she communicated with others was the biggest shift. “It’s no longer just me, right?” She explains. “There are all these other people, and finding that new language to describe what I had been doing almost on instinct with photography.”

“Their stories,” Osubu says, “moved beyond photographs.”

Dear Philadelphia is a stunning 28-minute debut documentary that only Osubu could have done. Because of her international background, her perspective, she was able to cut to the quick of what makes these stories universal. “There’s a part of the Black diaspora that’s connective. You get a sense of familiarity with that culture whether you’re in the US or the UK. Being Black in these spaces is impactful. In my heart, I want this film to reflect the Black community.”

Relatability was important; Osubu had to make these hyper-local stories engaging for a universal audience.

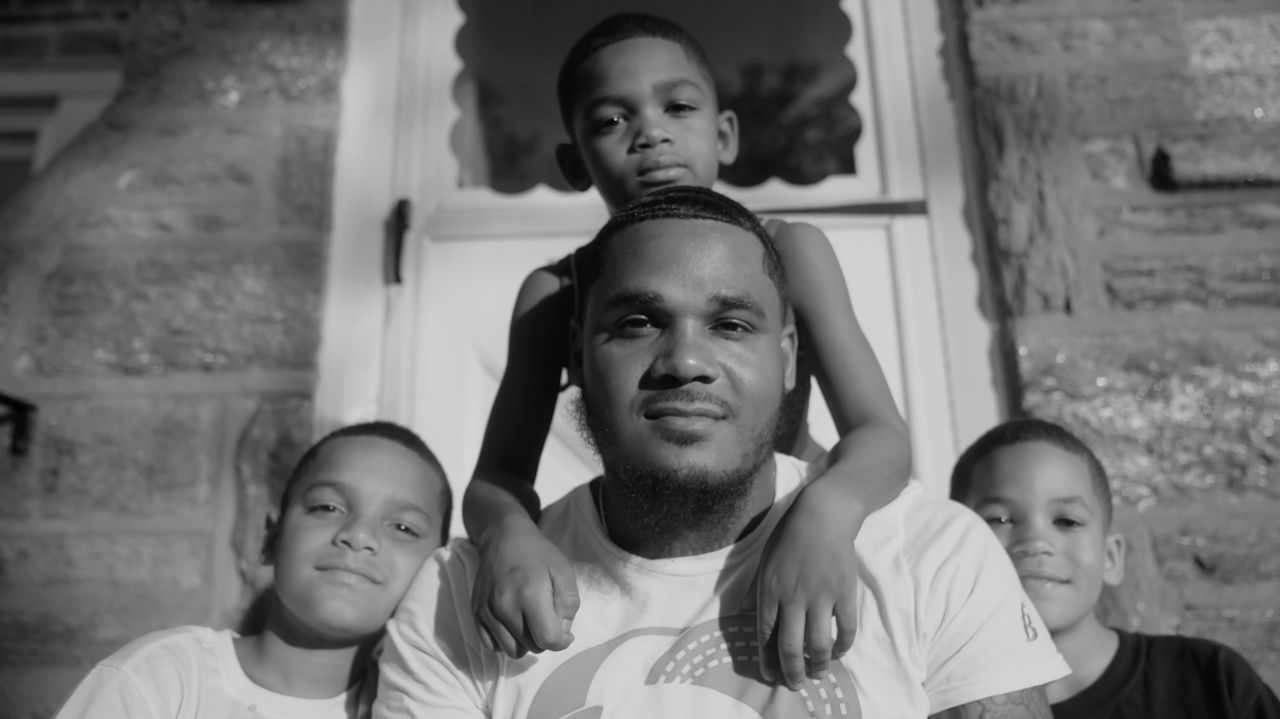

Dear Philadelphia is, at its core, about fatherhood, and how everyone is impacted by their father. Within this framework, there’s always something to relate to, to connect with. “It’s a huge responsibility to show to everyone how gender roles can be destructive to men. I focused on sensitivity and Black fatherhood because that tenderness is important, natural, and vulnerable, but it’s not often shown in media, or anywhere else.”

Osubu sought to find stories of forgiveness and grace. There is power in moving on, and power in realizing that it is not up to you to judge the people you see on screen. In the film, like in life, there are characters who thrive within their second chance. The film is also a second chance for Osubu.

“Around the time I made the film,” she says, “I lost my father.”

As she takes a deep breath, she seems to get more confident about her work. She says it was near to her heart to show fatherhood as a communal act that was both delicate and fragile. Dear Philadelphia is about overcoming your pain, persevering through the worst times, and finding beauty in strength.

"There’s a part of the Black diaspora that’s connective. You get a sense of familiarity with that culture whether you’re in the US or the UK."

“A lot of this ethos, my storytelling structure in general, is based on faith. I was exploring the characteristics of God in this film about Black fatherhood. I was learning about forgiveness, unconditional love, hope; and I found all those things reflected in Philadelphia, and ultimately, in the film. Even if I’m directing,” she says, smiling, pleased that we’ve gotten to this, the heart of her work, “I want to bring out God in every person. I want this film to be hopeful. I want to ask questions that are hard but show how people can work through things.”

"Whenever I describe the project I frame it as an archive of all these amazing people."

By showing the part of Philadelphia that is both humanizing and exceptional, Osubu found that her faith was reflected and shared every day during filming. She found that there were people everywhere taking on more than they were asked, being more than they were expected to be. She found God in Philadelphia, and through a camera, experienced a practical faith in every father she interviewed. Philadelphia’s fathers feel like Osubu’s second chance at reconnecting with her own late parent. Her debut film is a chronicle of love, Blackness, and faith.

)