How we perceive Black strength is holding us back

Strong, indefatigable, heroic... Black people are seen as tough customers because, well, they'd have to be to progress in a world - and in an industry - where the odds are stacked against them. But, argues Siân Blackman, Senior Account Manager at Creativebrief, being seen as strong could ultimately be a weakness in the fight for equality.

I’m sick of being a ‘strong Black woman’. Not because Black women aren’t some of the strongest people I know, I’m just sick of the ways this trope is holding our industry back.

That's not to say Black people haven't been shaped and hardened by tough experiences that make us stronger, but we don't have an endless reserve of inner strength, especially now, in 2020, when the trauma of seeing Black men and women senselessly killed is such a regular occurrence.

Beyonce is a machine. Michelle Obama, a superhero. Their strength is awe-inspiring, but in celebrating it we forget their humanity.

In the weeks surrounding George Floyd’s death and the London Black Lives Matter protests, I felt myself entering a depressive fog. I realise now that it was a form of exhaustion at the ever-present job we all have on our hands; the monumental task of creating meaningful change. I was exhausted by the inevitability of the initial outrage dying down, and company conscience moving on as quickly as my news feed..

We’ve certainly had a lot to contend with this year, but Black lives mattered before coronavirus and will continue to matter after. It’s important to acknowledge that a discussion around race and the period of transformation the industry finds itself in, are not exclusive. Instead they are interlinked, and, if you want to come out of this with a stronger culture and company than before, then you can’t afford to ignore the problem this industry has with race any longer.

Above: Michelle Obama, above left, with Oprah Winfrey, is considered 'a superhero', but are we forgetting her humanity?

That’s an opinion shared by Shanice Mears from creative agency The Elephant Room. Responding to an open letter from adland [sub required], she asked of those who had put their name to it: “Are the pledges genuine and are you ready to work?” Before going on to ask; “I’d like to know why it has taken a man to die, a world to protest, and an online movement telling you Black lives matter, for you to consider that Black talent is worth investing in”. Hearing these words made me realise I’d been asking the same questions, and haven’t stopped asking them since.

It’s damaging to rely on the stereotype that Black people, especially women, are unfalteringly strong.

And the problem, I believe, is rooted firmly in how we interpret strength and colour. How we perceive Black strength is not only holding our empathy back, but our ability to reform too. It’s damaging to rely on the stereotype that Black people, especially women, are unfalteringly strong and will take any and all hardships on the chin. When we talk about Beyonce, she’s a machine. Michelle Obama, a superhero. Their strength is awe-inspiring, but in celebrating it we forget their humanity. As our appreciation of strength goes up, the possibility of empathy plummets. We not only apply these traits to the biggest, most-lauded Black personalities, but to every person of colour.

For people of colour in advertising it’s not only hard to get in the room, but to stay there too. There’s a sense that if we expose any vulnerabilities, we’re confirming existing fears that we shouldn’t be there in the first place. In my personal experience, Black women who are going through very real mental health and stress-related issues don’t tend to admit as much to themselves, and don’t get support from the people around them because it’s presumed we’re always strong, not capable of breaking down, or that we’ll power through. My own anxiety has often been downplayed by others and in turn myself because of this. Pressure and expectation combine to make us walk a very fine tightrope.

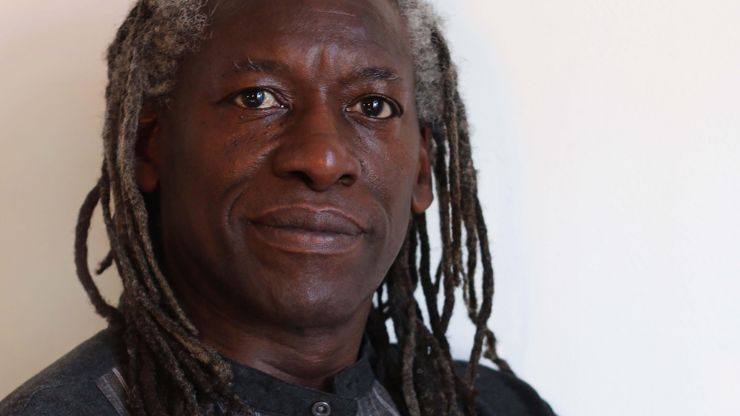

Above: Trevor Robinson and Karen Blackett are advertising role models but, asks Blackman, shouldn't their trailblazing have made the path easier to follow?

There needs to be more empathy with what people of colour in the industry have been through, and are still likely to go through, if we’re to truly commit to change. Without senior stakeholders actively advocating for us and being considerate of our experiences (whether from first-hand experience themselves, or putting in the work to learn about these experiences), people of colour remain on the outside, kept at arm’s length, or overlooked because it’s assumed they’re strong enough to go it alone.

The reality is that we can fit all the senior Black creatives in the industry into one neatly packed trade magazine article that celebrates them.

What we end up with is a huge gap between those people of colour the industry chooses to give recognition to, and those unable to progress, or even get a foothold, in an industry which doesn’t demonstrate a genuine willingness to understand them in a meaningful way. Incredible things have been done (and continue to be done) to pave the way for a better future, but when research from Creative Equals tells us that just 3% of CEOs are people of colour, we end up pinning our aspirations on the few figures of colour in the industry who prove it is possible to succeed.

Role models like Sarah Jenkins, Trevor Robinson and Karen Blackett should be celebrated for their trailblazing. But, by now, shouldn't the trail be a footpath for others to easily follow? The problem is that the industry too often looks to these figures and finds itself absolved of any worries it has that there’s still work to be done. When the reality is that, for example, we can fit all the senior Black creatives in the industry into one neatly packed trade magazine article that celebrates them.

For the Robinsons and Blacketts of this world, strength, too, is a problem. Imagine what it must be like to be put on a pedestal for young Black people trying to make sense of this industry. A personal hero of mine, Karen Blackett, recently referred to her exhaustion at being “everybody’s one black friend”; of feeling like “a unicorn in the industry”. What’s troubling is that Black marketing leaders are still few and far between, and that for the next generation of those looking for role models, there aren’t enough to go around.

Aimed at helping inclusion, [reactive diversity committees] can inadvertently perpetuate the feeling of ‘otherness’ that leaves people of colour feeling excluded.

For me, solving the issues our industry faces lays in far more than reactive diversity committees and team sessions. That’s not to say these can’t be useful, but their impact is limited and, too often in (predominantly white) companies, feel like box-ticking exercises. Exercises that give white employees the opportunity to scratch the surface of nuanced, meaty topics like racism, privilege and micro-aggressions, but fail to relate to or even recognise what it must feel like to have racism happen on their own doorstep.

It might look good on the KPIs but it doesn’t encourage deeper empathy for what the Black people in these companies have experienced – sometimes even at the hands of their colleagues, whether unknowingly or not. Aimed at helping inclusion, these sessions can inadvertently perpetuate the feeling of ‘otherness’ that leaves people of colour feeling excluded from both company culture and understanding in the first place. It has to improve. When companies ask themselves what they should be doing, Mears’s earlier question should be ringing in their ears; why has it taken so long? Companies need to think long and hard about whether they are committed to putting in the work, and that they’re in it for the long haul. They need to pledge that they won’t give up on their Black employees or put them on the back-burner, even when change becomes difficult or distractions threaten to divert the focus.

The moment we see Black people for more than just their strength is the moment we can move forwards.

The moment we see Black people for more than just their strength is the moment we can move forwards with empathy and equal opportunity. This article is not a request for people to tiptoe around me or any other Black person, and it’s certainly not an excuse to avoid the conversation for fear of getting it wrong. On the contrary, I like being able to passionately advocate for myself. But we’re much more than Black and Strong. We are vulnerable, nuanced, creative, exciting, and an asset to this industry. If more people recognise this and actively challenge the current narrative, this will put a stop to talent drain and change the industry for the better, with more people of colour seeing out lengthy, full, satisfying and rewarding careers in advertising.

If we get it right, we might even usher in the next generation of diverse leaders. Because where there is strength, is in numbers.

)

+ membership

+ membership