In transition: how brands can adapt to a changing gender landscape

Despite increasing queer visibility in advertising, transgender and non-binary representation remains a minefield for brands – with the Bud Light backlash a stark reminder of the risks of getting it wrong. Selena Schleh speaks to members and allies of the trans+ community about proper pronouns and performative versus true brand allyship.

From Pepsi’s infamous BLM-inspired boo-boo to Dove’s body positive packaging debacle, the landscape of marketing is littered with mishaps: stark reminders of the risks of venturing into sensitive territory to shift products.

'Go woke, go broke’, screamed a New York Post headline, as the trolls turned their attention to trans-inclusive campaigns.

This year, the battleground has moved to trans rights – and the cautionary tale comes courtesy of Bud Light. A seemingly innocuous TikTok post, featuring trans influencer Dylan Mulvaney sipping from a personalised beer can, unleashed a torrent of transphobic vitriol that swiftly spiralled into a brand boycott, a full-blown PR crisis and ultimately knocked Bud Light off the top US beer spot: a stark warning of how a social media backlash can lead to IRL consequences – hitting a brand where it hurts most, in the pocket.

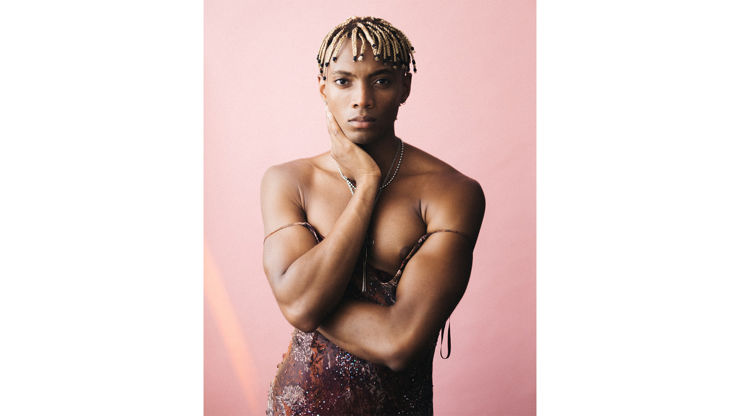

Above: Dylan Mulvaney’s Bud Light commercial

‘Go woke, go broke’, screamed a New York Post headline, as the trolls turned their attention to trans-inclusive campaigns by The North Face, Adidas, Calvin Klein, Target, Woolworths and Glamour – prompting some brands to backpedal on their Pride support, unwilling to engage with what had become a political hot potato. US retailer Target removed an entire range of merchandise by trans designer Erik Carnell from its stores, citing concerns for its employees’ safety.

There’s no room for performative gestures or empty commitments in 2023: love is love, but money talks.

Such was the fallout that Outvertising, a volunteer-led LGBTQ+ advocacy group for the advertising and marketing industries, issued an open letter to adland, calling on brands and agencies to stand firm on their marketing and support the trans+ community. Pointing out that the entire LGBTQIA+ community suffered the effects of this “targeted campaign of hate”, they concluded that “there’s no room for performative gestures or empty commitments in 2023: love is love, but money talks.”

With trans+ and non-binary representation in advertising already lagging behind other queer groups – a recent study by Channel 4 revealed just 0.3 per cent of adverts featured a transgender person – does the Bud Light backlash represent a permanent setback? Danielle St James, the founder and CEO of Not A Phase, a charity committed to supporting trans+ adults, hopes not – pointing to the progress that has been made over the past 20 years, when transgender inclusion was limited to pioneers working ‘stealth’ (i.e. without disclosing their identity).

Credits

powered by

- Agency iris Worldwide/London

- Production Company The Sweetshop/London

- Director Nicolas Jack Davies

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency iris Worldwide/London

- Production Company The Sweetshop/London

- Director Nicolas Jack Davies

- Producer Emily Hendrey

- Offline tenthree

- Post Production Time Based Arts

- Sound Factory Studios/London

- Creative Director Elinor Vasiliou

- Creative Giulia Frassine

- Creative Anny Heyden

- Agency Producer Richard Blaxill

- Art Production Lu Howlett

- Art Production Jody Brown

- Production Paris Bennett

- Editorial Director Vino Vethavanam

- Art Director Scarlett Clifford

- DP Ula Pontikos

- Executive Producer Justin Edmund-White

- Executive Producer Morgan Whitlock

- Producer Hannah Cooper

- Music Zebedee Budworth

- Executive Creative Director Grant Hunter

- Creative Richard Peretti

- Creative Matt Gray

Credits

powered by

- Agency iris Worldwide/London

- Production Company The Sweetshop/London

- Director Nicolas Jack Davies

- Producer Emily Hendrey

- Offline tenthree

- Post Production Time Based Arts

- Sound Factory Studios/London

- Creative Director Elinor Vasiliou

- Creative Giulia Frassine

- Creative Anny Heyden

- Agency Producer Richard Blaxill

- Art Production Lu Howlett

- Art Production Jody Brown

- Production Paris Bennett

- Editorial Director Vino Vethavanam

- Art Director Scarlett Clifford

- DP Ula Pontikos

- Executive Producer Justin Edmund-White

- Executive Producer Morgan Whitlock

- Producer Hannah Cooper

- Music Zebedee Budworth

- Executive Creative Director Grant Hunter

- Creative Richard Peretti

- Creative Matt Gray

Since then, mainstream beauty brands like Benefit and e.l.f. have hired trans and non-binary models, Mattel has released a genderless doll, and campaigns like Starbucks’ What’s Your Name and Mastercard’s True Name have shone a spotlight on the importance of identity and acceptance in an authentic and powerful way.

And despite the shrill opposition from conservative voices, they are, thankfully, a minority (albeit an extremely vocal one): new research from the Cultural Inclusion Accelerator (CIA) and the ANA’s Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing (AIMM) suggests 74 per cent of the general population in the US are comfortable with transgender representation in ads.

If the motive is to capitalise on rainbow season, do some naff one-of-every-sort campaign and donate 0.5% of the net profits from a product, don't bother.”

But brands who engage with the trans+ and non-binary community need to tread carefully – right from the beginning, cautions St James, who has worked with the likes of Omnicom, Nike, Soho House and Conde Nast on diversity and inclusion strategies. “The first thing that a brand should consider when using trans+ or LGBTQ+ talent is [their] motive. If it’s that they recognise the power they [as a brand] hold and the platform that they can give to issues that [the trans+ community] are up against, do it. If the motive is to capitalise on rainbow season, do some naff one-of-every-sort campaign and donate 0.5% of the net profits from a product, don't bother.”

‘Rainbow season’ – aka Pride – might seem the ideal opportunity for agencies and brands looking to boost their LGBTQIA+ credentials but, as Ravi Amaratunga Hitchcock, co-founder of Amsterdam creative studio Soursop, points out, “if you’re only thinking about the queer community, or even queer consumers, a couple of weeks before Pride, you should be worried. True engagement, understanding and trust with any community takes time and resource. Engaging, understanding and championing that community all year round as an agency is a must.”

Credits

powered by

-

- Production Company Local Boy

- Director Na Frenette

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Local Boy

- Director Na Frenette

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Local Boy

- Director Na Frenette

That was a key insight behind Soursop’s No Pride, No Sport campaign for Nike, which celebrated LGBTQIA+ athletes including a non-binary personal trainer as they explored their new values and identities through sport. It was deliberately released post Pride, long after most brands had packed up the rainbow flags, to underscore Nike’s year-round commitment to developing deep relationships with queer athletes and queer sporting organisations.

Advertising is guilty of opting for quick solutions to the deep and complex question of representation.

Despite the upbeat and celebratory nature of the content, the response was depressingly familiar, bringing the transphobic and homophobic trolls out in force. But in contrast to Bud Light, which went silent on social media, turned off comments and distanced itself from Mulvaney (it finally issued a lacklustre statement: “We never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people. We are in the business of bringing people together over a beer"), Nike and Soursop doubled down on their support for the queer sportspeople in their ad.

“Nike are a brand who consistently stand up for the communities they believe in,” says Amaratunga Hitchcock. “And Soursop as an agency was born because it wanted to platform and celebrate marginalised and alternative points of view. So we stood with the amazing and inspiring athletes who we worked with.”

Credits

powered by

- Agency RanaVerse/New York

- Production Company PRETTYBIRD/UK

- Director Jess Kohl

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency RanaVerse/New York

- Production Company PRETTYBIRD/UK

- Director Jess Kohl

- Executive Producer Juliette Larthe

- Producer Benji Landman

- Editor Gaia Borretti

- Colorist Alex Gregory

- Executive Color Producer Charlie Morris

- Music We Are Father

- Sound Clearcut Sound

- Producer Joshua Gochez

- Creative Director Rana Reeves

- DP Beatriz Sastre

- Titles Aleksi Tammi

Credits

powered by

- Agency RanaVerse/New York

- Production Company PRETTYBIRD/UK

- Director Jess Kohl

- Executive Producer Juliette Larthe

- Producer Benji Landman

- Editor Gaia Borretti

- Colorist Alex Gregory

- Executive Color Producer Charlie Morris

- Music We Are Father

- Sound Clearcut Sound

- Producer Joshua Gochez

- Creative Director Rana Reeves

- DP Beatriz Sastre

- Titles Aleksi Tammi

Caption: Jess Kohl directed a series of poignant films for Unilever’s United We Stand series.

“Safeguarding your contributors is really important,” agrees PRETTYBIRD director Jess Kohl, whose work often explores marginalised communities, such as Asia’s biggest transgender gathering in India. “Being transparent about your intention as a filmmaker throughout, including them whenever possible in decisions and consulting with them on how they are being represented. You’re being given a lot of trust as a filmmaker and often working with vulnerable people.”

And as one of the most vulnerable groups in the wider LGBTQIA+ community, trans+ /non-binary talent are owed a particular duty of care by those giving them greater visibility.

One of the most egregious examples of “how not to work with trans talent”, says St James, was Burberry’s B:MINE Valentine’s campaign, which featured transmasculine non-binary musician Campbell King and genderqueer creative Mia Maxwell in an embrace. In response to the transphobic backlash, Burberry quietly deleted the post against the models’ wishes, leaving them feeling abandoned and exposed.

If you’re only thinking about the queer community, or even queer consumers, a couple of weeks before Pride, you should be worried.

As King pointed out in a Gay Times interview, “We didn’t want the post to be removed because it’d be giving the impression to all the people who have directed hate that they’ve won. We wanted them to moderate the comments and to issue [a statement in] support for the trans community [or], at the very least, support for the models.”

When it comes to portraying the trans experience authentically, representation behind the camera is as important as the talent in front of the camera, but advertising still lags behind other industries, like TV, in this regard. Having previously worked in Channel 4’s commissioning department, Amaratunga Hitchcock noticed “a lot of representation of stories across the spectrum of gender and sexuality. Sometimes it’s tone deaf, and sometimes on point – but the effort is there.”

Nike – No Pride, No Sport - Joy Run Collective

Nike – No Pride, No Sport - Leon & Yassin

Caption: Nike’s No Pride No Sport films.

By comparison, he says, “advertising is guilty of opting for quick solutions to the deep and complex question of representation. There’s a lot of progressive casting and selection of stories, but without the representation behind the camera, or in the production company and agency involved. This can often extend to the brand teams involved too. And a disconnect between on and off-screen [representation] can often result in work coming across as opportunistic and not genuine.”

“Entering into environments like creative meetings or commercial sets as the sole queer individual can put pressure on that person to provide all of the insight about queer people, or make them feel put under a magnifying glass of inclusion,” adds Valiant Pictures’ Justice Jamal Jones, a non-gender-conforming filmmaker and advocate for Black trans and non-binary individuals who has directed films for Dazed, Calvin Klein and MTV. “As a talent I’m relieved when I see queer representation in agencies; I feel like I am better understood.”

If you know you are going into a sensitive area of identity politics, then you need to immerse yourself and truly understand the community you are engaging.

Too often, though, agencies consider the diversity and inclusion box ticked – and queer representation accomplished – by having “a white ‘office gay’” on staff, which doesn’t help with understanding other communities’ perspectives and leads to harmful guesswork, cautions St James: “Make sure you bring voices to the planning stages that represent the community involved.”

Jones agrees that tokenism is unhelpful – instead, the aim should be to source whole teams, as he has done as a director, both “to facilitate a positive atmosphere of acceptance and collaboration” and in order to create authentic work. And that might mean taking a punt on untested talent, as Soursop did for No Pride No Sport. Alongside pulling together a creative team that reflected the different facets of the LGBTQIA+ community in order to articulate authentically queer stories, they hired queer writer-director Abel Rubenstein, who had no previous commercials experience, to direct the job.

Above: Dani St James, Justice Jamal Jones, Jess Kohl, Ravi Amaratunga Hitchcock

As well as striving for representative staff, it’s important that agencies and brands ‘school up’ before any trans-inclusive projects, rather than leaving it to non-binary and trans+ talent to educate them: “If you know you are going into a sensitive area of identity politics, then you need to immerse yourself and truly understand the community you are engaging,” says Amaratunga Hitchcock.

That might mean bringing in external consultants such as St James, who does everything from running internal training sessions and focus groups, to assessing a brand’s messaging or how their product lines serve the community and collaborating on social media output and casting.

But real progress needs to be grounded in agency culture – not just when a project demands it. That could be championing queer talent for senior leadership and management roles, or encouraging the whole team – not just queer staff – to attend LGBTQIA+ cultural events, talks and festivals.

“I hope [the future of trans+ representation] will be really boring,” says St James, “with trans people being used in advertising the way that anyone else is used in advertising"

At Soursop, queer staff are supported to work for community specific charities and wider networks alongside their day-to-day agency work. Even simple changes, like including pronouns in e-mail signatures for all staff, can make a workplace more accommodating of non-binary perspectives.

Ultimately, as with all change, an industry-wide effort is required, says Kohl: “These conversations need to be being had by the wider industry, not just marginalised people and their allies.”

If that change does come about, what could trans+ and non-binary representation look like in five years’ time? “I hope it will be really boring,” says St James, “with trans people being used in advertising the way that anyone else is used in advertising, to sell a product or service and not to be forced to platform their identity to do so. Cast us in a Tesco ad scanning the oranges at the till in any other month than Pride month: it’ll be groundbreaking.”

)

+ membership

+ membership