Is it possible to work in advertising and have a conscience?

Would you work on a campaign for an arms company? Probably not. A tobacco company? No, it's illegal. At least it is in the UK, but how about elsewhere in the world? And what about fossil fuel? Or sugary drinks? Or alcohol? Moral decisions can sometimes be a maze of 'ifs and buts' and, as The Moon Unit outlines, while a moral framework is incredibly important, it's also fraught with dilemmas.

Picture the scene: You’re sitting on the toilet looking at your phone, when an email pings in from an agency that represents an arms manufacturer.

Would you be interested in doing a spot for the new KillCorp 3000?

Would you be interested in doing a spot for the new KillCorp 3000? A cluster missile that’s a massive improvement on the 2000, it liquefies the internal organs of enemy soldiers, poisons rivers, and renders all nearby farmland unusable for a century.

My guess is you’d say no.

Above: ‘Defence’ companies make adverts too, usually with big budgets

You’d rather take on the job for Father Constantine’s Sanctuary, which spends every weekday rescuing orphans, saving donkeys at the weekend. Problem is, moral decisions in advertising are rarely this black-and-white. They’re usually as grey as an old tea-towel.

If you think about it, there’s a moral issue with almost everything we advertise. Soft drinks and fast food cause obesity. Booze can create misery. Fossil fuels are evil, as are the motor cars and airlines that burn them. Banks are a cancer and mobile phones are manufactured using child labour. Go deep enough, and pretty soon you’ll find that all you can advertise are electric vehicles and underwear.

Moral decisions in advertising are rarely black-and-white. They’re usually as grey as an old tea-towel.

But, usually, we don’t go deep. What normally happens when we're faced with doing an ad in a morally dubious category, like gambling or pay-day loans, is that we get a ‘twinge’, and since there’s no moral philosophy professor nearby, we just go with our gut. Or, all too often, override our gut.

What we need is a proper framework to guide us. It won’t guarantee we’ll make the right decision – and, after all, Father Constantine could turn out to have been abusing those donkeys – but it will give us a clearer conscience knowing we’ve thought it through in a reasoned way.

Above: Moral decisions are rarely black and white. Alcohol unquestionably causes harm, but does that harm outweigh the pleasure of the vast majority who enjoy a beer or wine with their friends?

So, let’s look at three possible frameworks: Legal; the ‘weighing-scales’; and the ‘example’.

The legal approach says that, since it’s incredibly hard for an individual to make moral decisions, and arguably unethical for one citizen to sit in judgement over others, let’s just follow the law of the land. In other words, if a product can be legally advertised, let’s say it’s okay.

A criticism of this approach is that the law often lags.

This strategy has the advantage of simplicity, and seems to be the approach that most in our industry actually take. Back in the day, very few creatives refused to work on tobacco accounts. On the other hand, none protested when cigarette advertising was made illegal, and brands like Silk Cut and Benson & Hedges in the UK, and Camel and Marlboro in the US, all of which had produced decades of iconic advertising, went dark.

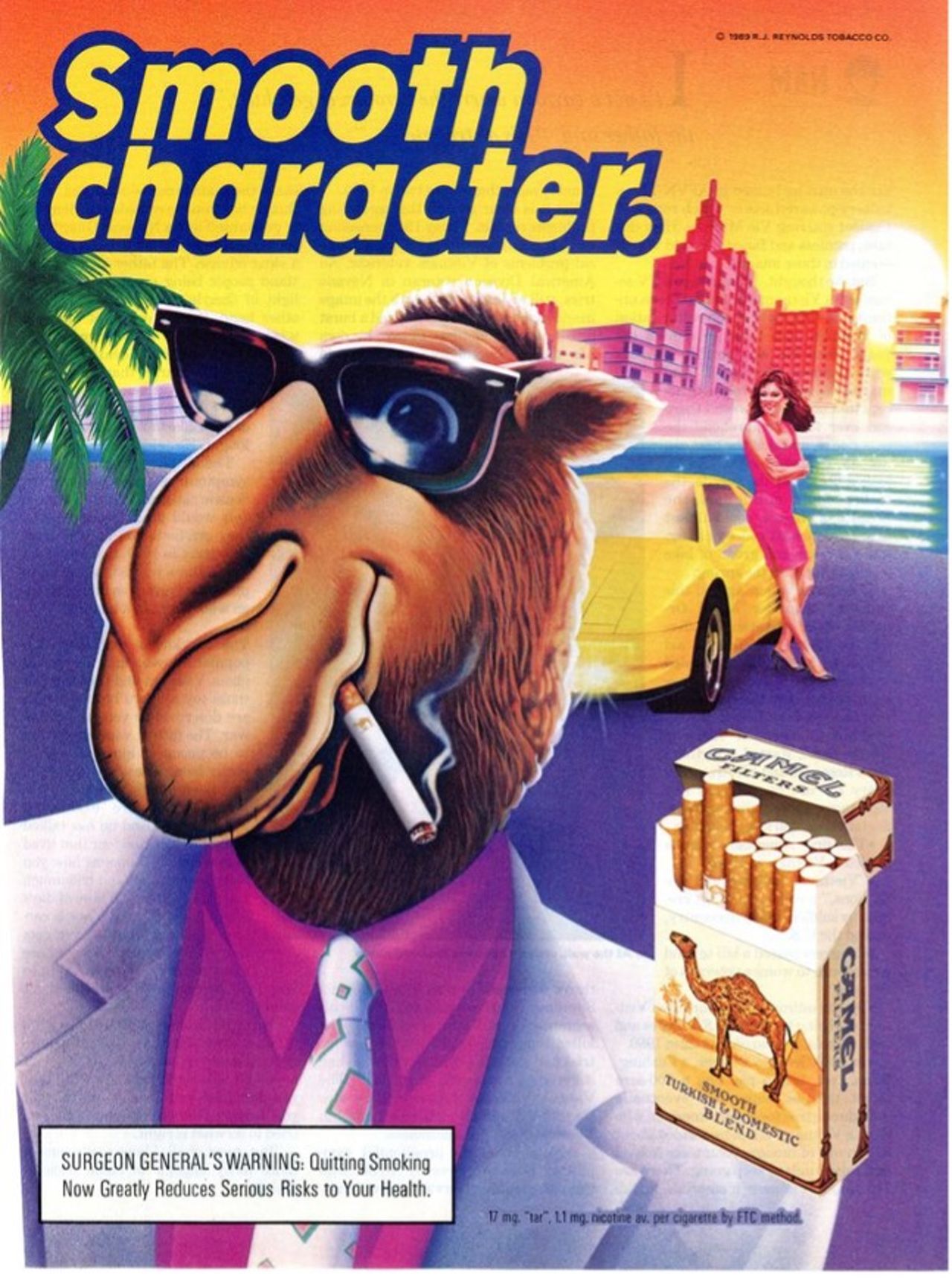

A criticism of this approach is that the law often lags. For example, cigarette advertising is still legal in many countries. Would you work on a tobacco ad for an overseas market? Probably not. The fact that it’s legal doesn’t seem enough to justify it.

Above: The iconic Joe Camel character is now illegal.

It feels like we should at least attempt to weigh the good we’re doing against the harm. Hence the second approach, the ‘weighing-scales’.

This idea produces more sensible decisions. For example, it rules out tobacco because even those who do smoke wish they didn’t, but it allows alcohol advertising, since although drinking unquestionably causes harm to a significant number of people, that harm doesn’t outweigh the pleasure of the vast majority who enjoy a beer or wine with their friends.

The tricky part of weighing the good versus the harm is that the harm is often uncertain.

The tricky part of weighing the good versus the harm is that the harm is often uncertain. Take gambling – a category growing so rapidly that eight out of the 20 English Premier League clubs currently have betting sponsors on the front of their shirts. Many people gamble quite safely and enjoy it but, on the other hand, problem gamblers have a 15 times higher risk of suicide than the general population.

How do you compare the effects of shooting one ad, which earns money for your family and provides valuable tax revenue to the government, with the possibility (not probability) that you may play a small part (along with many other factors) in driving someone to addiction? It’s a tough one.

Above: West Ham and Newcastle have betting sponsors on the front of their shirts, along with six other Premier League clubs.

A final approach is the ‘example’ rule. This states that you should take into account not just the harm caused by your action, but the possibility that your action becomes an example to others. This principle is demonstrated by the sign in museums that says ‘Please don’t touch the statues’. It won’t make a bit of difference if I touch the marble lion’s nose, but if everyone followed my example, the poor lion’s nose would wear away.

There’s no question that, right now, an ethical framework is more important than ever.

The ‘example’ approach is particularly relevant for us in advertising because we are, quite literally, setting an example to others. In showing motorists smiling at the gas station while they fill their car with liquid climate change, we are telling the viewers at home that this is okay. So, for us, it seems appropriate to go beyond the calculus of our own individual actions, and take into account the power we possess to influence others.

At The Moon Unit, we’ve certainly taken a bit of a stand. We won’t work for fossil fuel clients, we signed the Clean Creatives pledge back in 2019, and we encourage you to do the same. It is possible to have a conscience if you work in advertising, especially if you’re a freelancer (typically the case for producers and directors), who can choose to reject a job if it smells like misery or greenwashing.

And there’s no question that, right now, an ethical framework is more important than ever. Tobacco products generally only killed the people who used them, whereas fossil fuels, left unchecked, could kill us all.

)

+ membership

+ membership