Meena Ayittey: Showing it like it is

The daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, Meena Ayittey eschewed her parents’ conventional career aspirations to forge a successful career in the creative industries. Recently signed to Great Guns, she finds rich filmic inspiration in the concept of racism, from her heartrending tribute to the Black Lives Matter movement to a new documentary lifting the lid on creatives of colour and the challenges of adland.

Even on a dodgy Zoom connection, Great Guns director Meena Ayittey radiates energy. But behind the smiles, she’s pretty tired.

Tired of the ‘double consciousness’ experienced by many Black people – “where you don’t only see yourself through your own eyes, but also through the white gaze, which takes up so much energy”. And tired of the “deafening” talk of diversity in the creative industries – the panels and presentations, the brainstorming sessions, the thought pieces popping up like mushrooms on LinkedIn feeds – when she is still, more often than not, the only Black person round the table.

You had these historically very white agencies and brands suddenly promising their solidarity – and then… tumbleweed.

“We say we want change, but do we really?” Ayittey ponders, pointing to #BlackOut Tuesday, a social initiative that saw Instagram covered with little black squares in support of Black Lives Matter. “You had these historically very white agencies and brands suddenly promising their solidarity – and then… tumbleweed. I don’t want to sound cynical, but [talk and no meaningful action] is a recurring problem in our industry.”

Frustration with this inertia led Ayittey to make Black Creative: Race and the Advertising Industry, an hour-long documentary, produced through Great Guns, which examines the challenges faced by people of colour through candid interviews with the likes of Trevor Robinson, CCO of Quiet Storm, Magnus Djaba, CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi London, and Sereena Abassi, Worldwide Head of Culture and Inclusion at M&C Saatchi. Currently in talks with a streaming service to host the doc, Ayittey hopes its reach will extend beyond adland. “It is quite industry specific, but I think I’ve kept it digestible enough that people from any sector will be able to relate to bits,” she says. “So, it’s really important to me to put this where everyone can see it.”

Above: A trailer for Ayittey's documentary, Black Creative: Race and the Advertising Industry.

As the daughter of Ghanaian immigrants with no ties to the creative industry, directing was an unlikely choice of career for Ayittey. “When you come from an African background, you’ve got three career choices: doctor, lawyer, or a disgrace to the community,” she jokes. Her filmic education began with watching the entire Disney back catalogue on “a dusty old VHS player” while her mother, a nurse, worked double shifts. Later, she devoured MTV during the glory days of Chris Cunningham, Jonathan Glazer and Spike Jonze. “Those guys really shaped my imagination,” she remembers. “Music videos looked like short films. The fact you could tell a story in three, four minutes was just such an amazing concept to me.”

If you have these feelings of hatred towards someone you’ve never even met, you’re denying yourself so many opportunities – including, perhaps, getting your life saved.

She came to directing via a circuitous route: a degree in fine art at Central St Martins, where she was repeatedly told by her (white) tutors that her robotic sculptures weren’t “Black” – and therefore commercially marketable – enough. “I saw [art] as a means of personal expression,” she sighs. “I didn’t really take it upon myself to speak for the entire Black race at the age of 18. So that killed my dream of becoming a fine artist.” Instead, Ayittey dove into the world of post production, landing her first job as a runner at Rushes, and going on to specialise in 3D VFX and motion graphics with stints at Framestore, Sony and Grey. But the dream of directing lingered. One weekend, shortly after starting at Grey, she pulled together a crew of 20 – contacts she’d made via a filmmaking collective at Framestore – borrowed a load of equipment from the production department, and shot her first short film, Flint.

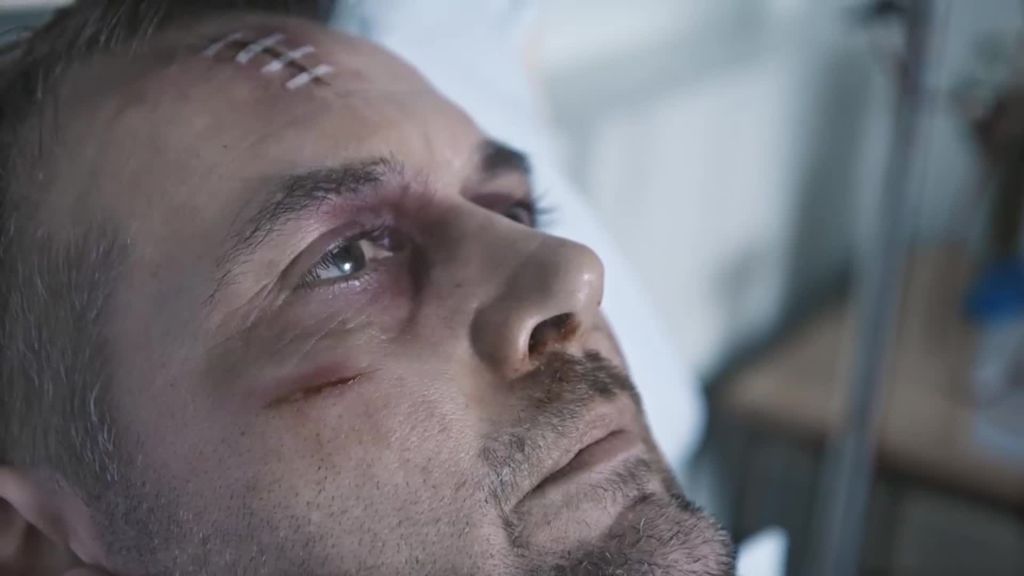

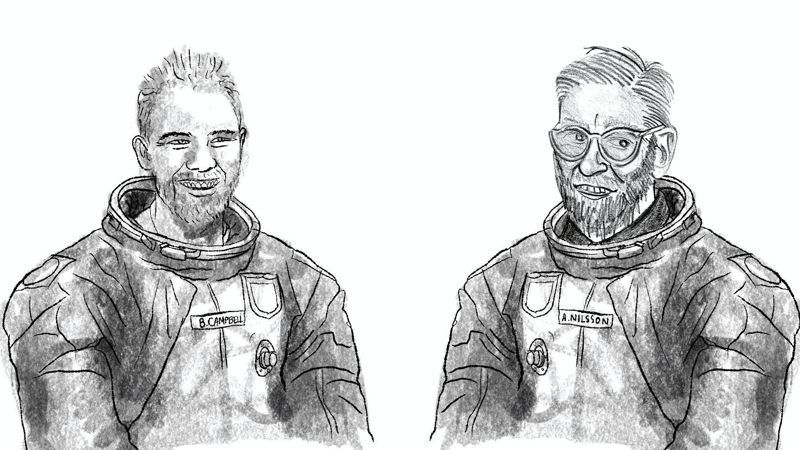

In the film, the title character – a hardline racist thug who calls Black people ‘spear-chuckers’ and is demoted by his own far-right party for being too radical – wakes up in hospital following a car accident, to discover he’s been given a life-saving blood donation by a Sudanese immigrant. “I was thinking about what a pointless concept racism is,” explains Ayittey. “If you have these feelings of hatred towards someone you’ve never even met, you’re denying yourself so many opportunities – including, perhaps, getting your life saved.”

Credits

powered by

-

-

- Director Meena Ayittey

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Director Meena Ayittey

- Producer Stacey Kelly

- Production Designer Sinead O'Malley

- DP Bruno Downey

- Editor Vesna Nikolic Ristanovic

- Editor Craig Coole

- Colourist Holly Greig

Credits

powered by

- Director Meena Ayittey

- Producer Stacey Kelly

- Production Designer Sinead O'Malley

- DP Bruno Downey

- Editor Vesna Nikolic Ristanovic

- Editor Craig Coole

- Colourist Holly Greig

Above: Ayittey’s short film, Flint.

The film also reflects the changing face of racism in Britain: while Flint is all bristling aggression, his fellow party member Marshall covers his equally nasty views with the fig leaf of political correctness. When Ayittey’s parents arrived in the UK in the 70s, it was the era of the National Front – ‘Go Home’ slogans daubed on walls and racial slurs – but Ayittey’s own experience has been more nuanced, more concerned with systemic racism: “More often than not, I’ve been the only Black woman in the creative role. There are plenty of Black cleaners and porters, but not creatives or directors.”

If you want your company to be more diverse, hire more Black people, more brown people, more women. It’s as simple as that.

Flint’s success on the UK short film festival circuit was the boost Ayittey needed. “It gave me that confidence that I was lacking as a director, [because of] not seeing [other] people like me. I thought, I can actually do this!” After moving to Fold7, she convinced the agency to back her second short, Home – a film exploring mental illness and shifting realities – which also picked up a slew of awards, and inspired her to start looking for representation. At Cannes Eurobest in 2019, she got chatting to fellow jury member Laura Gregory, and ended up signing to Great Guns.

Credits

powered by

-

- Production Company Great Guns/UK

- Director Meena Ayittey

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Great Guns/UK

- Director Meena Ayittey

- VO Stephanie Flowers

- Editor David Warren / (Editor/VFX Supervisor)

- Sound Designer Liam Conwell

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Great Guns/UK

- Director Meena Ayittey

- VO Stephanie Flowers

- Editor David Warren / (Editor/VFX Supervisor)

- Sound Designer Liam Conwell

Above: Ayittey's film for the Black Lives Matter movement, Mama.

With brand work for Canon, Amazon and Hugo Boss under her belt, the subject of racism continues to inspire Ayittey as a filmmaker. Earlier this year she added her voice to the Black Lives Matter movement with Mama, a video created in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. Urgent and powerful, Mama overlays shocking footage of police brutality with a heart-wrenching speech by US Senator Stephanie Flowers. Though Flowers’ words were hugely impactful on their own, Ayittey decided to add the clips “to show people what was going on. They actually need to see the violence and the injustice.”

[People] need to see the violence and the injustice.

When we speak, the news has just broken that no murder charges will be brought in the case of Breonna Taylor, the unarmed Black woman shot in her Louisville home during a police raid. Is Ayittey planning a follow-up to Mama in response? “Just to get into the headspace to explain, visually, why this is so horrific – why you’re essentially saying: ‘this Black body doesn’t matter, it’s worthless, we’re not going to punish the people who did this’ – it’s just exhausting,” she replies.

Ayittey might be tired, but she remains hopeful that change will come. “I do believe that most people are good and fair: they want to help fight this cause, they want to be allies and they ask me how they can do that. And it’s [with] action. Words are cheap. So, if you want your company to be more diverse, hire more Black people, more brown people, more women. It’s as simple as that.”

)

+ membership

+ membership