The agent provocateur of animation

Smashing out animated promos for the likes of Radiohead, Run The Jewels, The Killers and many more, Chris Hopewell's punk rock approach has shaken up the world of stop-motion and given it a Mohican to boot. David Knight meets the Black Dog Films director.

We all know that animation takes time – sometimes a long time.

Stop-frame animation, in particular, is a painstaking, labour-intensive process, requiring extraordinary attention to detail and dedication to the craft. It takes months, perhaps even years, to get the end result. Right?

Well, actually, wrong. Not if you are Chris Hopewell. Born and bred in Bristol, a celebrated hub for animation, Hopewell cuts a genial anti-establishment figure, a rebel in the field of stop-frame animation. His approach is rather more rock ‘n roll than that of his peers. And when you press ‘Go’ on a Hopewell music video, you will definitely get the finished film back in weeks, not months.

“The longest we've ever spent on a video was the Run The Jewels video, which was four weeks - that's from conception to delivery,” Hopewell says, talking to shots from his home in Bristol. “There's a lot of companies here that do very beautiful, artful stuff. But it takes a long time. We go at it with more of a punk attitude."

Credits

powered by

- Artist Run the Jewels

- Executive Producer Amaechi Uzoigwe

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Producer Rosie Brind

Credits

powered by

- Artist Run the Jewels

- Executive Producer Amaechi Uzoigwe

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Producer Rosie Brind

Hopewell has directed music videos with plenty of attitude, for Radiohead, Father John Misty, Franz Ferdinand, The Killers, The Bees, the aforementioned Run The Jewels and more. He is certainly less concerned about slick production values, or visual perfection, than he is about the impactfulness of his stories. They are often provocative and hard-hitting, which work notably well played out to a soundtrack of social-conscious hip-hop, or melancholic alt-rock.

You can polish the life out of animation, and I think a lot of people do these days.

For instance, in the grimly satirical video for Run The Jewels’ Don’t Get Captured, RTJ’s Killer Mike and El-P ride a funfair ghost train that takes them on a journey through the injustices and horrors of gentrification, authoritarianism, and class-based oppression, played out by a cast of skeletons.

In his first of his two darkly comic videos for Father John Misty, for Things It Would be Helpful To Know Before The Revolution, a young survivor of the Apocalypse, trundles her belongings in a shopping trolley through a destroyed city and airport, past dangerous adversaries – knife-wielding rats and boozed up cockroaches. In the second for Please Don’t Die, an armature version of Josh Tillman (aka Father John Misty) descends into the Underworld, crosses the River Styx and flirts with Death.

Father John Misty: Things It Would Have Been...

Father John Misty – Please Don't Die

And in Radiohead’s Burn The Witch – the video that marked Hopewell’s return to directing after a break of several years – an animation style strongly influenced by ‘60s children’s TV is applied to a storyline redolent of The Wicker Man, to powerful and chilling effect. That award-winner took just two weeks of round-the-clock work to make, from start to finish. It looks marvellous, but Hopewell also left some of the imperfections in the finished piece.

“You can polish the life out of animation, and I think a lot of people do these days,” he declares. “Often it's so beautifully done you might as well just film it in live action. [With Burn The Witch] I would set up all the scenes and then our DoP Jon Davey would put a camera on it, we'd rejig it a little bit and then we'd shoot it. If you turned some of the puppets around, you’d find they were held together with pins on the back. I don't think that would go down well at Aardman.

It's a weird Cinderella story. I’d never made a film before and suddenly you get asked to make one for Radiohead.

“If you've got a good idea and you've got the people there as a team to help, you can do this stuff really quickly," he continues. "You just need meticulous planning at the beginning, the actual animation doesn't take that long. Maybe companies like Aardman get two seconds a day or something like that because of their level of professionalism but with us, we would be getting up to 20 seconds a day, being a bit less professional!"

Credits

powered by

-

- Production Company Jacknife

- Director Chris Hopewell

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Jacknife

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Post Production Buckloop

- DP Jon Davey / (DP)

- Art Director/Prod. Designer Chris Hopewell

- Animator Andrew Stuart

- Producer Rosie Lea Brind

- Editor Ben Foley

- Animator Virpi Kettu

- Animator Louie McNamara

- Animator Oli Putland

- Animator Aaron Hopewell

Credits

powered by

- Production Company Jacknife

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Post Production Buckloop

- DP Jon Davey / (DP)

- Art Director/Prod. Designer Chris Hopewell

- Animator Andrew Stuart

- Producer Rosie Lea Brind

- Editor Ben Foley

- Animator Virpi Kettu

- Animator Louie McNamara

- Animator Oli Putland

- Animator Aaron Hopewell

Hopewell’s punk rock attitude probably stems from the fact that, back in the day, he was indeed a punk rocker. Remarkably, the evidence exists in one of the most famous stop-frame animated music videos of all time – Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer. He and a friend were streetcast as extras in the video that was filmed in Bristol back in 1986, and Hopewell can be spotted, with his Mohican haircut and biker jacket, for a few seconds in its final moments.

But his proper introduction to the craft of animation came several years later. In his late 20s he became serious about the creative arts, and work in graphics developed into an interest in model-making and creating moving sculptures during an art foundation course. “A tutor said: ‘you've put all this effort into your work to make it move, why don't you just animate it?’ I'd never really thought about that before.”

He applied to take the new animation degree at Newport University in South Wales, and got in. During his course, he went back to Bristol to work at independent animation studio Bolex Brothers, that specialised in stop motion animation, on work experience. “Then I completed my final degree film at Bolex and was lucky enough to work on a few of their big commercials before they closed, so learnt a hell of a lot.”

By then, Hopewell knew all about the filmmakers who created the animated films he loved as a child: Ray Harryhausen, director of the 7th Voyage Of Sinbad and other animated epics; Czech masters Jan Svankmajer and Jiri Trnka; and Oliver Postgate, idiosyncratic British creator of TV shows Pogle’s Wood, Bagpuss and The Clangers. Postgate in particular would be a huge influence on his breakthrough work.

Above: Hopewell hard at work for Run The Jewels' Don't Get Captured video.

Contacted by Dilly Gent, Radiohead’s video commissioner, who wanted to make an animated video for the first single from their album Hail To The Thief, he was handed the chance to direct a Postgate-influenced video. “It's a weird Cinderella story,” he says. “I’d never made a film before and suddenly you get asked to make one for Radiohead. Those guys trusted me to do it, which was pretty amazing.”

The result was There There, itself a dark fable, set in a magical forest populated by anthromorphised furry animals, with Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke as a ne'er-do-well, lured to the forest by the promise of treasure to steal, and suffering a terrible comeuppance.

“I was trying to make it look like some odd, beautiful Eastern European fairy tale - the kind of stuff that I was brought up watching," he says. “Postgate’s Pogle's Wood is [also]one of the basic references for the video: little creatures creeping around the wood; animation that isn't too clean; animation that has a life and a rawness to it.”

Credits

powered by

- Post Production Collision Films

- Artist Radiohead

- Director of Photography Fred Reed

- Commissioner Dilly Gent

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Producer Susannah Gent

Credits

powered by

- Post Production Collision Films

- Artist Radiohead

- Director of Photography Fred Reed

- Commissioner Dilly Gent

- Director Chris Hopewell

- Producer Susannah Gent

There There won an MTV VMA, and springboarded Hopewell into a frantic blur of activity through the rest of the Noughties. He made numerous music videos, often combining animation with live action. Among Hopewell’s own favourites in this period are The Knife’s Marble House, the story of three mice that live under the floor in a house, which he says is “totally inspired by Oliver Postgate”; The Zutons’ Confusion (“a bit of an homage to Svankmajer”); and The Bees’ Who Cares What The Question Is, which represents his first and so far only foray into claymation.

Then he co-directed a movie, A Fantastic Fear Of Everything, starring Simon Pegg, with Crispian Mills (also frontman of 90s band Kula Shaker). As well as acting as art director on the movie, Hopewell also directed two extended animated sequences – stories told by Pegg in the film.

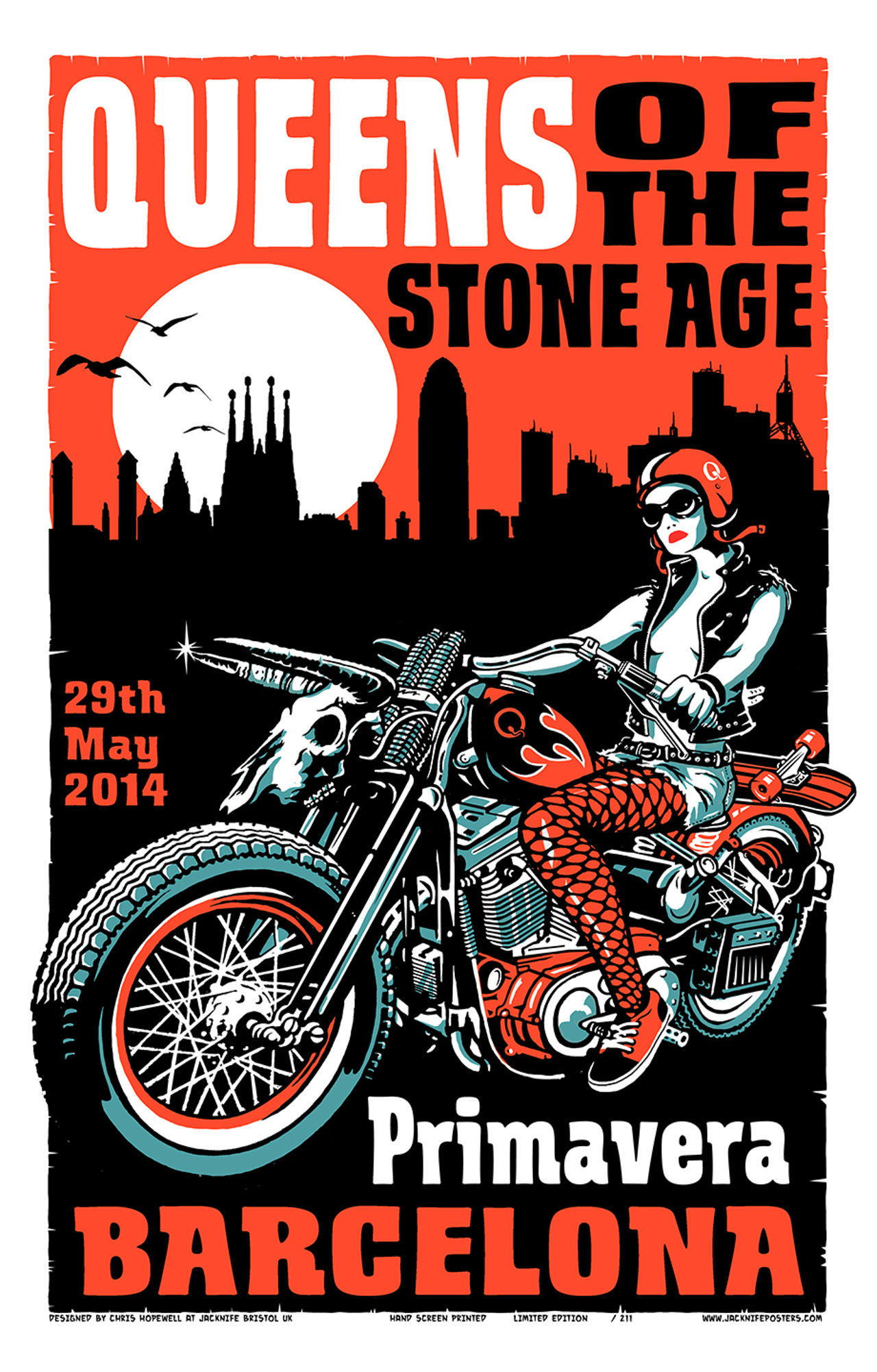

By the time the movie was finished, Hopewell wanted a break from film, and another creative endeavour was increasingly occupying his time: hand-screenprinting custom-designed posters for gigs. “I discovered this beautiful medium, and I thought I'd love to have a go.” He set up Jacknife as his screening printing arm, designing bespoke posters for the likes of The Killers, Queens of the Stone Age, Foo Fighters in the classic poster art style – which then grew to become his whole business.

“We travelled round the world and did exhibitions all over the place, and I enjoyed that more than I did the film work for a while. Designing and screen printing is just you on your own. It was nice to do that, just to get a bit of head space.”

Applying the type of animation we do to sell cheese is not easy. It takes a leap of faith to put money behind our look and our process.

After several years out of the game, Hopewell assumed his directing days were over. But then Stanley Donwood, the artist who works closely with Radiohead, approached him in early 2016 about creating moving image work for the campaign around the band’s new album, A Moon Shaped Pool. “I'd been working with him on some print-based projects, and when he suggested this I said: ‘I don't really do that anymore.’

We went out and got a bit drunk on cider and by the end of the evening, he said: ‘If you did do something, what would you do?’ Then I came up with this concept based on very simple, old school animation techniques and he took the idea to Thom and Thom said, ‘Go for it.’” The result was Burn The Witch.

Above: a screen-printed poster produced by Jacknife.

Now re-established as a director and leader of a working animation studio, and represented by RSA Films for commercials, he is nonetheless sanguine about his style and working methods being taken up by advertisers. As everything must be agreed and approved before the shooting process begins, a commercial client would have to show the same level of trust as his select group of music clients. “Applying the type of animation we do to sell cheese is not easy,” he reflects. “It takes a leap of faith to put money behind our look and our process.”

Instead, he sees the future beyond music video commissions in more longform projects. Hopewell has written a feature film script – “a biopic of quite a famous band” – which will be live action, with the band’s backstory achieved in animation. After a recent trip to the US, this feature project now has a high-profile producer on board. “If all the wheels get in motion, that could all kick off in the next few months.”

He also harbours an ambition to bring the style of animation that delighted him as a child, and still delights him, to the attention of a new generation of children. “I would love, in some small way to maybe do something that Oliver Postgate did,” says Hopewell. “I was so influenced as a kid by these very simple stories, that were simply told. I would love to do the same.”

)