The face of fear: How clowns became a modern horror archetype

Coulrophobics beware; Michael Shlain, director and co-founder of Butcher Bird Studios, explores how the image of the clown in film and advertising has always straddled fun-loving and frightening.

When a recent road trip found me burning rubber through Tonopah, an erstwhile mining town in the middle of the Nevada desert, I saw something that caused me to slam on my brakes and audibly exclaim to no one at all “You’ve got to be f***ing kidding…”

What would otherwise fit the description of a roadside Motel was maroon-colored, polka-dotted and covered in giant hand-painted cutouts of big-haired, big-shoed, big-smiling clowns. An appropriately garish sign announced that I had stumbled upon the (dubiously) 'World Famous' Clown Motel.

On the spectrum between 'Clown-Positive' and 'Anti-Clown', I have always considered myself fairly 'Clown-Neutral', and yet, as I approached the door to the “FREE museum and gift shop,” some unconscious force stopped me in my tracks. I felt physically unnerved as if dreading a confrontation with the kind of mind that would dream up such a place. In the name of curiosity and a good story, I finally overcame my hesitation and entered.

Creepy clowns have arguably overpowered their 'happy' cousins in cultural representation.

But where, I wondered, did this unexpectedly visceral clown-aversion come from?

Boasting a collection of 2000 clown artefacts, the Clown Motel touts itself as “America’s Scariest Motel.” Such a claim isn’t controversial today. Lots of people are creeped out by clowns, and there is an entire horror sub-genre devoted to them.

Above: The "World Famous" Clown Motel.

Creepy clowns have arguably overpowered their 'happy' cousins in cultural representation. In 2016, McDonald’s cancelled their long-reigning Clown Prince of Marketing, Ronald McDonald, amidst an international Phantom Clown Panic (the second in American history.) Arch-rival Burger King then kicked the clown when he’s down with a series of successful scary-clown-themed ads and activations. Recent years have also seen a bona fide shortage of professional (read “happy”) clowns both in the US and abroad. Happy clowns are quite literally dying out.

But clowns weren’t always scary.

While the trope of the “vengeful clown” has a history dating back to the nineteenth century (Poe’s Hop-Frog and the opera Il Pagliacci feature all-to-human clowns driven to murder), it wasn’t until the 1980s that the clown image morphed into something inhuman and demonic. This new “monster clown” archetype emerged spontaneously and grew into a phenomenon in popular culture.

The word 'Coulrophobia' (the widely-accepted and very-official-sounding term for a fear of clowns) is a recent invention.

The 1980s gave us films like Poltergeist (1982) and Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988), novels like Stephen King’s It (1986), and wrestlers-turned-hip-hop-impresarios Insane Clown Posse (1989). Even the word 'Coulrophobia' (the widely-accepted and very-official-sounding term for a fear of clowns) is a recent invention; a pop-neologism of dubious origin that first appeared on an anonymously authored web page in 1995.

So how did clowns (of all things) become a modern horror archetype?

The 1980 trial of John Wayne Gacy is often cited as a catalyst for popularizing the “killer clown” image. And 1981 saw the (first) Phantom Clown Panic, where children in various cities reported sightings of creepy clowns attempting to lure them into their vans. While these real-life horror stories no doubt tarnished the clownish image in the public imagination, they don’t seem sufficient to explain how persistent and psychologically “sticky” the scary clown phenomenon continues to be.

Above: In Praise of Shadows' video essay, The History of Scary Clowns.

Carl Jung suggests that to understand phobias, we must look to the contents of the 'collective unconscious'; the shared ancestral images, archetypal stories, and memories common to all mankind. What we now recognize as 'clowns' emerged independently across cultures in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. For this reason, it may prove useful to examine them as a manifestation of the 'Trickster' archetype.

In Western Civilization, we see early incarnations in the Stupidus and Moriones of Ancient Rome, the Court Jesters of Medieval Europe, and the Harlequin and Pierrot stock character of Renaissance Commedia Del Arte theatre. These were low-class characters notorious for poking fun at the ruling classes, speaking “truth to power” under the (dis)guise of humor (sometimes at the peril of their lives). Conversely, in Native American traditions, to be a Clown was a sacred and respected calling.

Across epochs, the Trickster Clowns played a very important role in society. Their job was to stand outside of culture and authority and poke holes in them; showing off just how fallible and impermanent our man-made rules, structures (and egos) are. As Alan Watts observes, these 'Jokers' were a reminder and a warning not to take ourselves or our institutions too seriously. Things fall apart, and so do we. It’s all a game; and like all games, it will come to an end.

By the 20th Century, the clown’s character had fundamentally changed ... he had lost his ambivalence.

By the 20th Century, the clown’s character had fundamentally changed. Most conspicuously, he had lost his ambivalence. Whereas the clowns of old embodied a range of human emotions from joy to pathos, the new clown was exclusively, relentlessly happy. This one-note paradigm reached its apotheosis in 1949 with Bozo who (thanks to television) became 'The World’s Most Famous Clown' (and who by his own admission “always laughs, never frowns.”)

According to historian Linda Simon, the emotional sanitization of clowns began in the 19th century as circus owners realized the increased profit of marketing their shows as “family entertainment.” And so, clowns doffed their “shades of grey” to attract the children, marking another deviation from their trickster roots. For the first time in history, clowns had become salesmen.

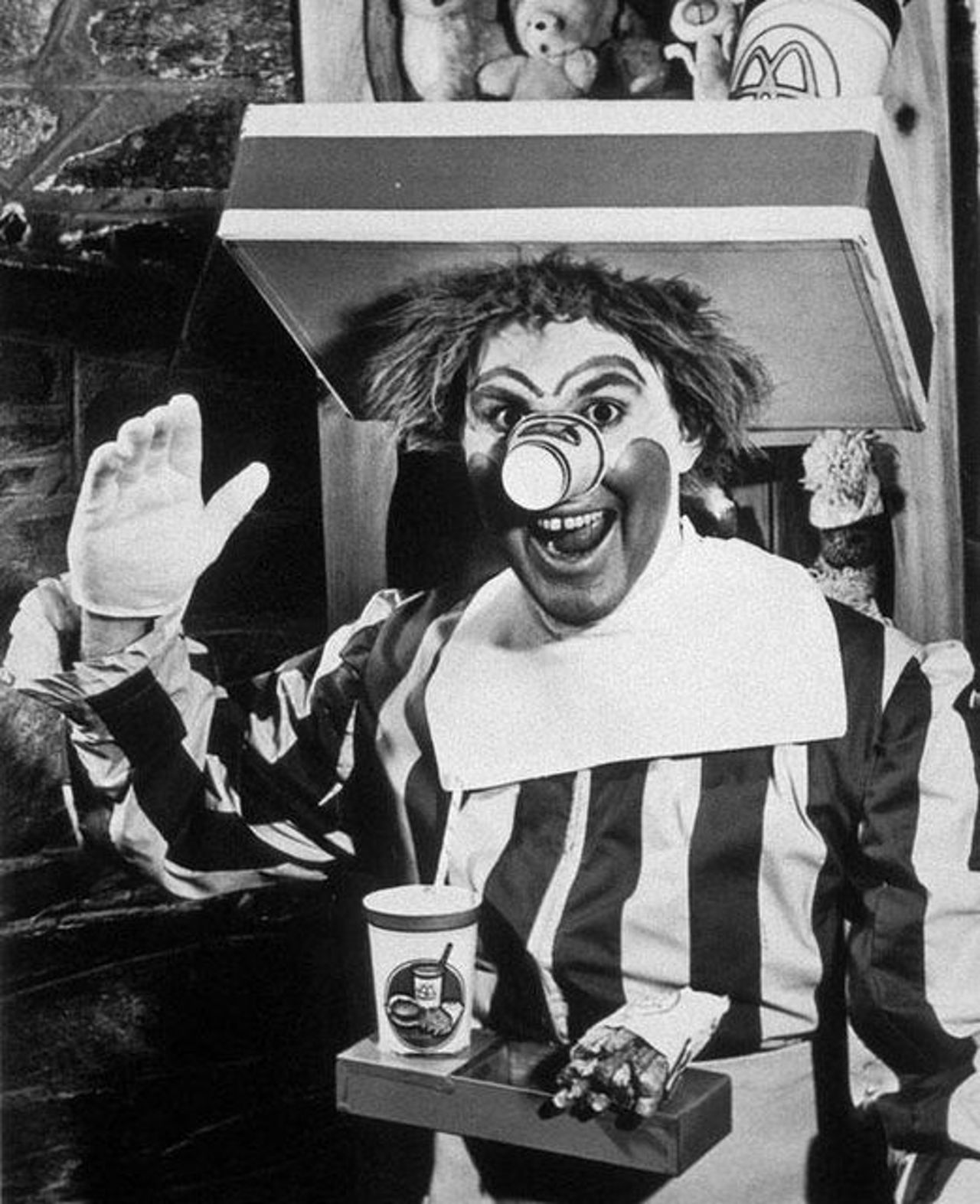

Above: An early version of Ronald McDonald, from 1963.

With the advent of television in the 1950s, enthusiastic, happy clowns sold everything from sneakers to breakfast cereal to chocolate-flavored-malt-extracts. And they were exclusively selling to children. In 1960, a Washington DC area McDonalds saw a 30% jump in sales after sponsoring an episode of Bozo’s Circus. When Bozo was canceled in 1963, Mcdonald’s hired Bozo actor Willard Scott as their very own Hamburger-Happy Clown, Ronald McDonald.

Like his Big Top forebears, Ronald’s mission was to market directly to kids. While later ads got better at disguising these intentions, an early McDonald's spot features Ronald dismissing a child’s concerns of “stranger danger” and plying him with free hamburgers. The message is clear: Ignore your parents and trust McDonald’s.

The clown’s painted smile has always hid an ulterior motive.

In 1986, a national poll (not surprisingly conducted by McDonald's) claimed that Ronald McDonald was recognizable by 96% of American children (second only to Santa Claus). Ronald had unseated Bozo as the world’s most famous clown-- just as 'scary monster clowns' were beginning their march upon the earth.

While the 'old trickster clowns' were anti-establishment, the 'modern happy clown' was co-opted by the establishment and became its face. Where the 'old tricksters' questioned authority, 'modern clowns' bypassed parents and usurped their authority. While the 'old trickster' humorously checked institutions for the health of the people, 'happy clowns' were busy enticing children into circus tents, cereal aisles and burger joint play-places with the intent of getting them hooked on over-sweetened nutritional garbage. While not quite the same as using candy to lure junior into a van, both harbor an ulterior motive.

To be fair, the clown’s painted smile has always hid an ulterior motive. The difference lies in the motive. The end of the 'trickster clown’s clowning is to reveal a truth. While the modern clown is probably trying to sell you something.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Leo Burnett/Madrid

- Production Company Only 925

- Director Rodrigo Cortes

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Leo Burnett/Madrid

- Production Company Only 925

- Director Rodrigo Cortes

- Post Production Serena

- Executive Creative Director Francisco (Pancho) Cassis

- Art Director Fred Bosch

- Chief Creative Officer Chacho Puebla

- Creative Director Fabio Brigido

- Copywriter Tomas Ostiglia

- Producer Florencia Caputo

- Producer Cesar Baciero

- Producer Diego Baltazar Macias

- Executive Producer Maria Jesus Horcajuelo

- DP Rafa Garcia

Credits

powered by

- Agency Leo Burnett/Madrid

- Production Company Only 925

- Director Rodrigo Cortes

- Post Production Serena

- Executive Creative Director Francisco (Pancho) Cassis

- Art Director Fred Bosch

- Chief Creative Officer Chacho Puebla

- Creative Director Fabio Brigido

- Copywriter Tomas Ostiglia

- Producer Florencia Caputo

- Producer Cesar Baciero

- Producer Diego Baltazar Macias

- Executive Producer Maria Jesus Horcajuelo

- DP Rafa Garcia

Perhaps this is the reason we don’t trust clowns anymore.

Several generations have now grown up with modern clowns who betrayed their ambivalent trickster roots to advance a consumerist agenda. And when these neutered 'happy clowns' cut off and buried their transgressive antisocial parts, it would not be long before these repressed “shadow” traits would come roaring back to life in the form of 'scary monster clowns'.

But at the risk of laying too much blame at the door of the golden arches, may I suggest what we’re seeing play out in Clown-dom is a reflection of the world we’re living in.

Several generations have now grown up with modern clowns who betrayed their ambivalent trickster roots to advance a consumerist agenda.

Right now, many people are waking up to the lies and machinations behind the painted smiles and candied words of leaders and authority figures. Meanwhile, we witness a growing enthusiasm for banishing comedians who make uncomfortable cultural observations. With no more space for 'jesters' and 'heyokas', clowns are no longer calling out the hypocrisy of institutions and instead seem to be running them. And these very institutions, seemingly once solid, are shaking, crumbling and collapsing around us. Without the spirit of the wise trickster teaching us to accept change, our reaction to the thunderstorm is one of abject terror.

The emergence of 'scary clowns' may have balanced the scales, returning us to a state where clowns once again represent the full spectrum of human experience. Like everything else in the world right now, clowns are polarized into two extreme camps.

Whether we shall yet see a reconciliation between 'happy' and 'scary' clowns, or a new paradigm altogether, only time will tell.

In the meantime, I’ll see you at the Clown Motel.

)

+ membership

+ membership