Aaron Duffy: In tech we trust

As we continue our focus on tech, Tim Cumming talks to 1stAveMachine director and SpecialGuest founder Aaron Duffy about marrying creativity with tech innovation and why you need to mix things up to get people to take notice.

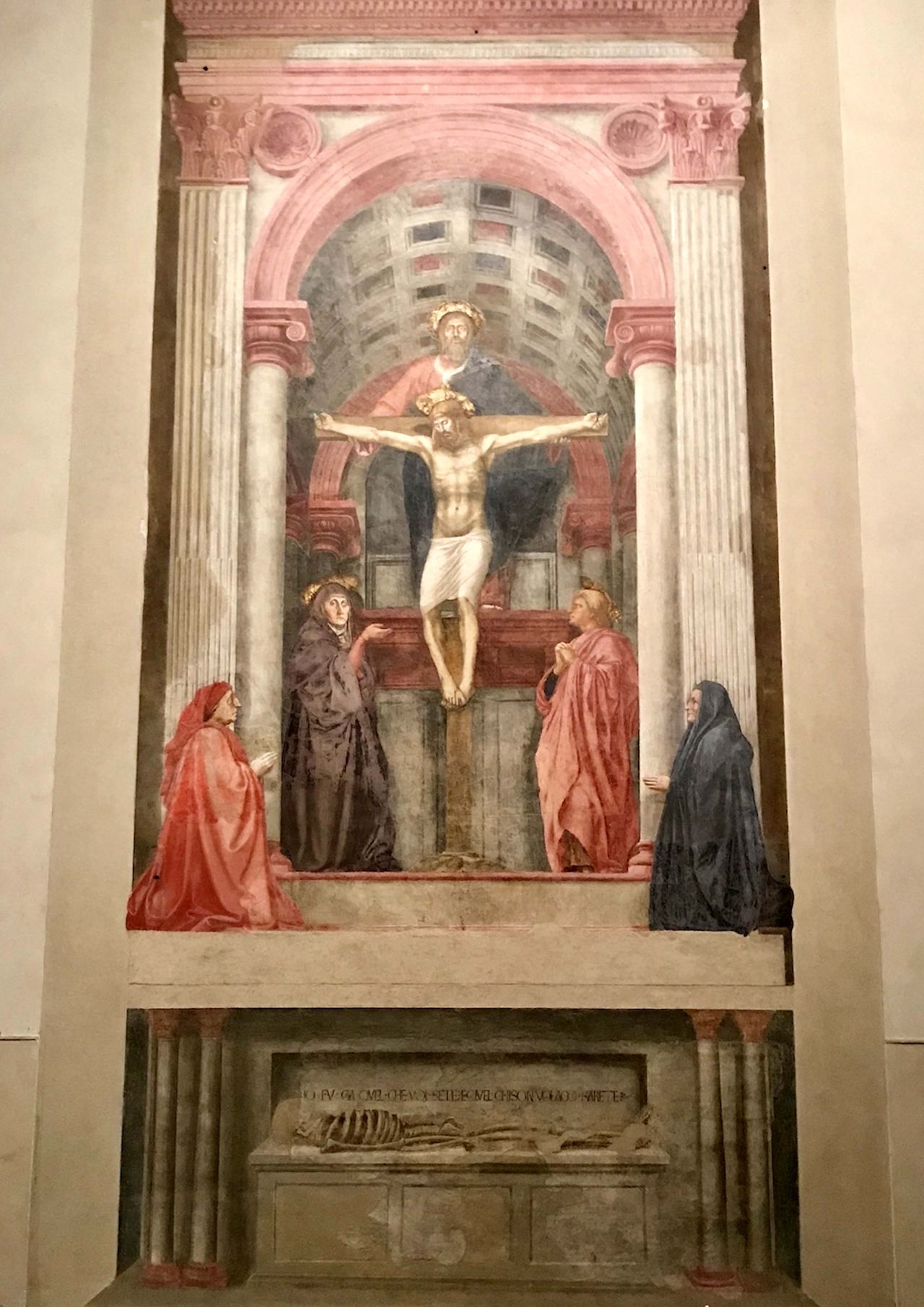

There’s a basilica in Florence, with a fresco by Masaccio, The Holy Trinity, painted in the 1500s, and it’s known to be one of the first examples of linear perspective, which was the cutting-edge tech of that time," says Aaron Duffy.

One of the big issues in advertising is that the more clean and beautiful something is, the more you distrust it.

"Masaccio was hired to come up with a painting that would really draw people into the church, and he used the technology of linear perspective, and the first people who saw it saw this amazing thing, a flat wall that looked like it had depth. Nothing had really had that before. It probably brought tons of people to the church. That’s our job as well. Not to just think, ‘video is good as a technology, so we’ll use video’. That’s the wrong way for us to think. No one’s going to come to the church we’re advertising for if it’s like all the other churches.”

No one’s going to come to the church we’re advertising for if it’s like all the other churches.

Duffy is a director of award-winning spots at multi-media production company 1stAveMachine and founder and ECD at SpecialGuest, which provides creative, strategic and production services by working one-to-one with brands. His very first piece of work for 1stAveMachine, which he joined in 2007, was Audi Unboxed, and it won a Cannes Lion.

Above: Masaccio's The Holy Trinity.

The spectacularly staged Google Speed Tests, with BBH, won seven more in 2011, while Google’s first ever TV spot, Parisian Love, became one of the most singular of all Super Bowl commercials, and has racked up more than nine million views since it went viral in 2010. In 2015 he topped Business Insider’s list of '30 Most Creative People in Advertising Under 30' and his most recent work, for clothing company Rag & Bone, and SnapChat’s first global campaign, Real Friends, featuring no less than 250 videos across 12 different markets, extends into AI and robotics, and the kind of AR that thrills 17-year-olds on SnapChat.

Duffy has an eye for drawing on the furthest limits of technological innovation.

As such, Duffy has an eye for drawing on the furthest limits of technological innovation, in AI and robotics at one end and at the other, the hand-crafted world of object-making and crochet – he’s pretty good with a hook – that he employed for the first Google Chrome campaign, Experiments. Between these two highly divergent technologies, between AI and needlework, his creative approach aims to encompass a full 360 degrees, rather than one fixed degree of viewpoint, and with the base technology of innovative creative thought itself guiding the way, augmented by all the tech the 21st century can bring to the screen.

The fantasy of Silicon Valley is that things are made and experimented with in a garage, and we brought that to the Chrome ads with the speed tests and the experiments.

Three generations of Duffy’s family came from a decidedly New York-centric profession – licensing Broadway musicals. Duffy’s would have been the fourth generation to enter the family business, had he chosen copyright law over art school at Washington University in St Louis. “None of us went into that,” he says, “but we all went to a lot of musicals.”

Credits

powered by

- Agency Google Creative Lab/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine/UK

- Director Aaron Duffy

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Google Creative Lab/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine/UK

- Director Aaron Duffy

Credits

powered by

- Agency Google Creative Lab/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine/UK

- Director Aaron Duffy

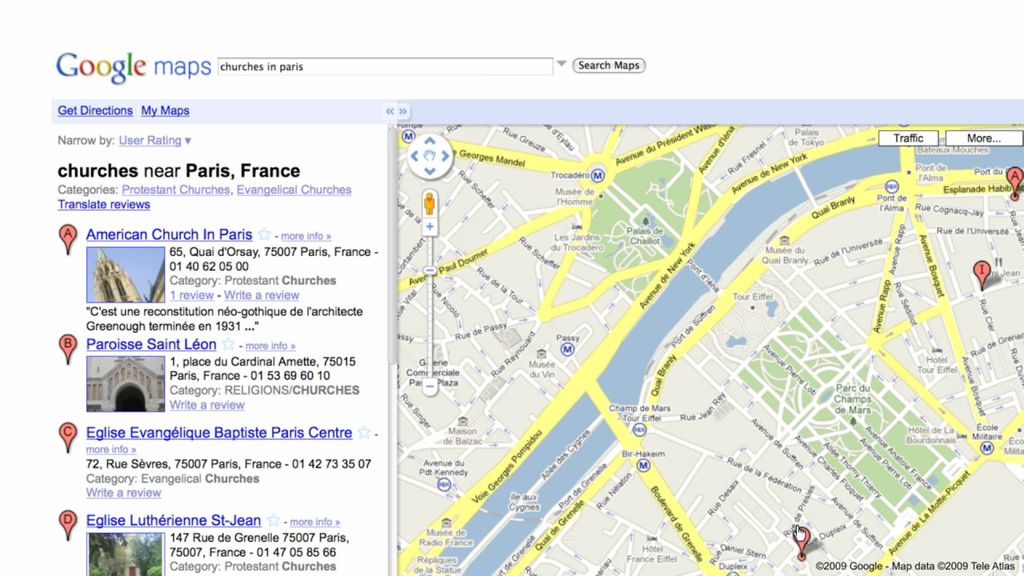

Above: Google's first TV spot, Parisian Love.

At college, he wanted to be a fine artist or sculptor, but fell in love with animation and video – even though there wasn’t a class on either of them. So, he set about learning by himself, the handmade, home-schooled way. “I did illustration and storyboards to figure out how to get my ideas across,” he says. Soon after graduating, he partnered up with Serge Patzak and Arvind Palep, co-founders of IstAveMachine, where he delivered his first spot, Audi Unboxed, and created the crocheted film short SpecialGuest, which was quickly picked up by the Saatchi Collection.

For his recent trio of films for Rag & Bone, Duffy drew on a range of major tech and filmmaking talents.

“That was when I used to make and shoot everything myself,” he says, somewhat wistfully. “I did that in my parent’s attic. The lighting is really crappy.” There’s a crocheted YouTube interface in Chrome Experiments, too, that was all Duffy’s handiwork. “When you do it you can feel for a moment what it’s like to be a machine,” he says, “this repetitive, monotonous movement, going over and over again, and then you come out with something beautiful.”

Credits

powered by

- Agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) New York/United States of America

- Production Company 1stAveMachine

-

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) New York/United States of America

- Production Company 1stAveMachine

- Agency Producer Orlee Tatarka

- Creative Steve Peck

- Creative Jared Elms

- Director Aaron Duffy

- Producer Meagen Carroll

- Creative Director Calle Sjonell

- Creative Director Pelle Sjoenell

Credits

powered by

- Agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) New York/United States of America

- Production Company 1stAveMachine

- Agency Producer Orlee Tatarka

- Creative Steve Peck

- Creative Jared Elms

- Director Aaron Duffy

- Producer Meagen Carroll

- Creative Director Calle Sjonell

- Creative Director Pelle Sjoenell

Above: Google Speed Test.

That hand-crafted technological ethos bleeds into his CG work, too. Back in 2007, the glossy patina of After Effects was dominant, “but I felt the style that came out of a lot of After Effects work became too perfect and clean,” he says. “It felt too beautiful. One of the big issues in advertising is that the more clean and beautiful something is, the more you distrust it. Out of school, I rebelled against perfect, beautiful things, motion graphics, animated things.” Which made it the right time, he adds, to meet IstAveMachine’s Patzak and Palep, “who were figuring out how to take high-end CG and combine it with raw, sloppy footage”.

The fantasy of Silicon Valley is that things are made and experimented with in a garage.

Cue Audi Unboxed. “It was all done in CG but I worked hard on making the roughness and textures of the cardboard and the tactile aspect of it really come out. From then on, a lot of people started looking to get that honesty and rawness into their brand work.”

That home-grown aesthetic continued with the Speed Test campaigns, working with Google Labs to fashion a number of Heath Robinson-esque contraptions to speed-test browser reaction against potato guns and the like. “We had to find a way to reach people, coming from the world’s biggest internet company, but it had to feel special and home-grown,” says Duffy. In other words, they didn’t want it to look like an advert. “The fantasy of Silicon Valley is that things are made and experimented with in a garage, and we brought that to the Chrome ads with the speed tests and the experiments.”

We had to find a way to reach people, coming from the world’s biggest internet company, but it had to feel special and home-grown.

As for Google’s first TV spot, Parisian Love, a charming story played out in search questions on the Chrome screen, it was as basic, technologically, as it gets. “It had the lowest production value you can imagine,” exclaims Duffy, “which is screen capturing the browser. But it helped set up their style of storytelling, even today.”

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBH/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine

- Director 1st Ave Machine

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBH/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine

- Director 1st Ave Machine

- CD Nick Kidney

- CD Kevin Stark

- Creative Maja Fernqvist

- Creative Joakim Saul

- Producer Olly Chapman

- Free Agents x Patricia Claire Co

- Creative Director Arvind Palep

- Producer Belinda Blacklock

- Producer Anna Lord

- Exec Producer Michael Adamo

- Exec Producer Serge Patzak

- Animation Passion Pictures

- Director Russell Brooke

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBH/London

- Production Company 1st Ave Machine

- Director 1st Ave Machine

- CD Nick Kidney

- CD Kevin Stark

- Creative Maja Fernqvist

- Creative Joakim Saul

- Producer Olly Chapman

- Free Agents x Patricia Claire Co

- Creative Director Arvind Palep

- Producer Belinda Blacklock

- Producer Anna Lord

- Exec Producer Michael Adamo

- Exec Producer Serge Patzak

- Animation Passion Pictures

- Director Russell Brooke

- Aaron Duffy

- Director 1st Ave Machine

- Song "Riding In My Car (The Car Song)" Woodie Guthrie

Above: Duffy's work for Audi, Unboxed.

For his recent trio of films for Rag & Bone, Duffy drew on a range of major tech and filmmaking talents. For Why Can’t we Get Along?, the first of the three, independent filmmaker Tony Hill and City of Lost Children cinematographer, Darius Khondji, worked on creating unexpected perspectives with the camera, while Radiohead's Thom Yorke provided the music and choreographer Benjamin Millepied the movement. Then came Last Supper, with tech pushed to the edges of what we know via the AI neural networks of artist and creative technologist Ross Goodwin.

AI in the real world is still … confused.

“We did an experience instead of a film,” says Duffy. “A 50-person VIP dinner, with the dinner hosted by AI.” Outside of glossy sci-fi movies, AI in the real world is still … confused, it transpires. This AI party host had a camera ‘eye’ and a neural network to interpret what that ‘eye’ saw. And it could talk about it, too. “It would say, that’s someone holding a plate, or sitting down,” says Duffy.

Rag and Bone – Why Can't We Get Along

Rag and Bone – A LAST SUPPER - rag & bone FW19 collection

Above: Two of Duffy's projects for fashion label Rag & Bone.

“And while it could identify certain actions and objects, much of what it talked about was either nonsensical or had some context that was very confusing.” Like the frankly disturbing artworks produced by other AI programs, one senses vast gaps in machine learning – gaps that will inexorably close, perhaps, as the level of machine understanding of how we humans perceive reality rises like sea-levels towards something approaching singularity.

The third Rag & Bone film stuck with the future tech theme by focusing on human tracking and robotics. “We got Madrid-based creative studio Espadaysantacruz to program the robot from scratch. We’ve been working together for two years now,” says Duffy, “and whenever I have a techy job to work on – really deep tech – we really can get into it with them.”

Deep tech, low-tech, hand-crafted or robotic, Duffy’s work draws down from across the technological spectrum. “We need to use cutting-edge technologies, if not create our own technologies,” he says, “in order to do our jobs well. That’s been done since the Renaissance, basically. And that’s part of our job.”

)

+ membership

+ membership