Henry Scholfield on the moving world of music videos

From sundry synchronised Will Youngs to complex camera choreography for Wiley and Stormzy, Henry Scholfield has always found new and exciting ways to drag the viewer into his work. Tim Cumming speaks to the Caviar director about finding the emotional connection in his artist-driven promos.

When it comes to making awesome, insightful, surprising and involving grime and pop videos that don’t just reflect the song in the obvious ways, but opens it up via a visual banquet of choreography and dynamic camera movements as balletic as the dancers and singers they capture in mid flow, there are few to match Henry Scholfield.

His way into the industry was immersing himself in breakdance contests and rap battles as a teenager and capturing the ensuing mayhem on home video. In many ways, he’s still in that world, intent on finding the best angles for his shot, but now it’s for Stormzy’s Vossi Bop or Wiley’s Peckham-set mini-epic Boasty, the latter featuring a grime gallery of walk-on stars – Stefflon Don stopping the traffic, Sean Paul, with Wiley himself played by a kid named Brooklyn, and the Don of British actors, Idris Elba, sliding on through.

The inspiration for Boasty, says Scholfield, came directly from the “oneupmanship” of those long-ago rap battles.

Credits

View on-

- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a shots membership

Credits

View on- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

- Post Production Electric Theatre Collective

- Managing Executive Producer Sorcha Shepherd

- Executive Producer Daniella Manca

- Producer Javier Alejandro

- Production Manager Zoe Travica

- Production Asstistant Daphne Do

- DP Kaname Onoyama

- 1st AD Tom Kelly

- 1st AD Daniel Smith

- Art Director Oian Arteta

- Lead 2D Op James Belch

- 2D Op Alex Grey

- Post Producer Antonia Vlasto

- Colorist Luke Morrison

- Editor James Rose

Explore full credits, grab hi-res stills and more on shots Vault

Credits

powered by- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

- Post Production Electric Theatre Collective

- Managing Executive Producer Sorcha Shepherd

- Executive Producer Daniella Manca

- Producer Javier Alejandro

- Production Manager Zoe Travica

- Production Asstistant Daphne Do

- DP Kaname Onoyama

- 1st AD Tom Kelly

- 1st AD Daniel Smith

- Art Director Oian Arteta

- Lead 2D Op James Belch

- 2D Op Alex Grey

- Post Producer Antonia Vlasto

- Colorist Luke Morrison

- Editor James Rose

“When I was starting out I recorded them on my sister’s handycam,” he recalls. “I thought I was making the best documentary ever. It was all oneupmanship and ‘screw you’ and barging each other out the way.” It was also his training ground as a director – he’s one of the few who never attended film school.

Those early rap battles may remain locked in on the DV tapes they were recorded on, but his first proper videos weren’t long in coming, the first for Example, on Mike Skinner’s label, then Professor Green. “The video for [Professor Green's] Upper Clapton Dance was me, two friends, a cast of his mates and a Nikon D90 camera (basically a shit version of a 5D), shooting it all in his old ends (neighbourhood) – but it came out great.”

Credits

View on- Director Henry Scholfield

Explore full credits, grab hi-res stills and more on shots Vault

Credits

powered by- Director Henry Scholfield

It’s still up on YouTube, and came so early in Green’s career that he hadn’t even fixed his teeth (“like a witch doctor’s necklace” as one YouTube sage points out). Smile or no smile, it got him signed to Virgin, and gave Scholfield his first paid work as a director, with an AD and a budget. “I loved it straight away,” he says. “I had been producing commercials at Partizan – a lot of animation and live-action mix. That was my day job. I needed to pay my way and in the evenings and weekends I’d write treatments and shoot videos. It was about fitting it in where I could.”

Artists are artists. They always have very different personalities.

Since then, he’s signed with Caviar and delivered stand-out videos for the likes of Kano, Will Young, Wretch 32, Dizzee Rascal, multi-faceted Belgian genius Stromae, Dua Lipa, Rosalia, Billie Eilish and Stormzy.

It’s an eclectic line-up, and it’s all about the talent, he says. “Stormzy and Dua Lipa are very different artists in terms of genre, but in some ways very similar. Both are super creative and very collaborative,” he says.

“Artists are artists. They always have very different personalities. There’s no specific trait that matches a genre with personality. But there is a through-line with great artists across genres and in different disciplines. I’ve met great choreographers, a few great actors, and really great directors, and the great ones are very calm. They’re very focused. They’re very driven, and they get to the thing very quickly, and they’re smart.”

He laughs. “Really smart.”

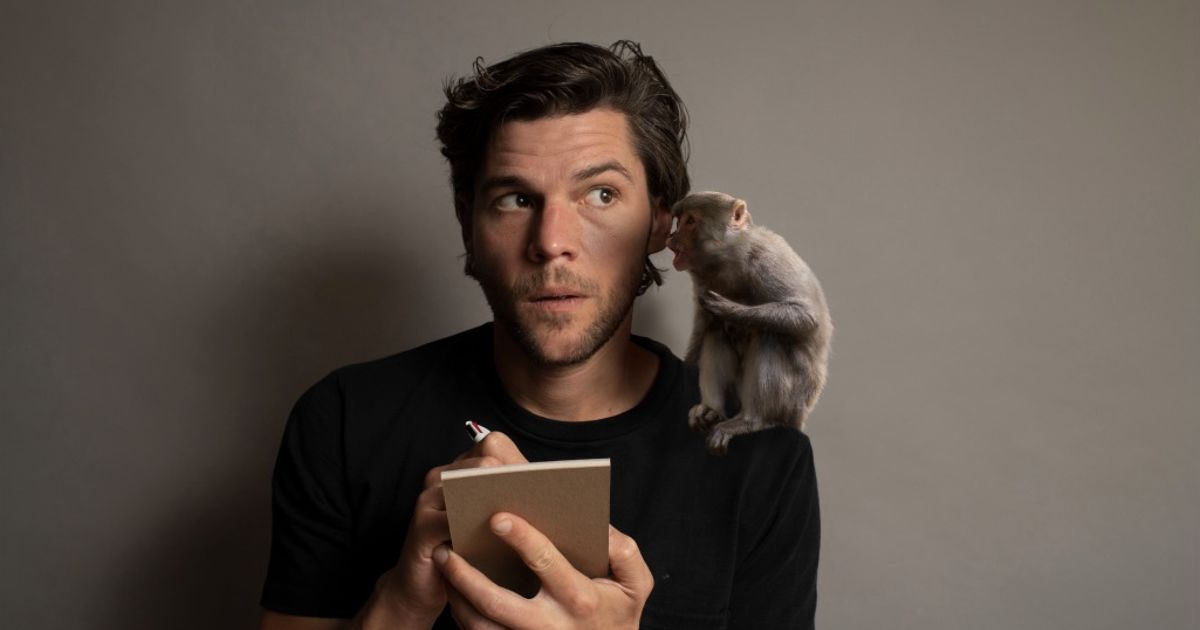

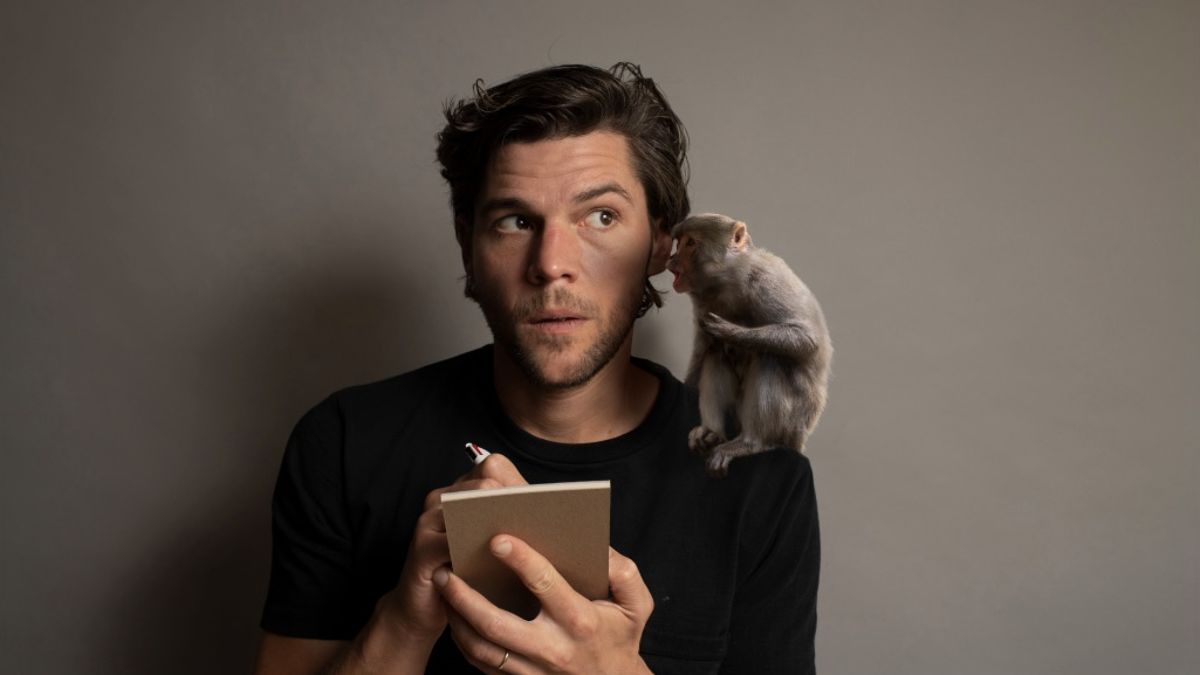

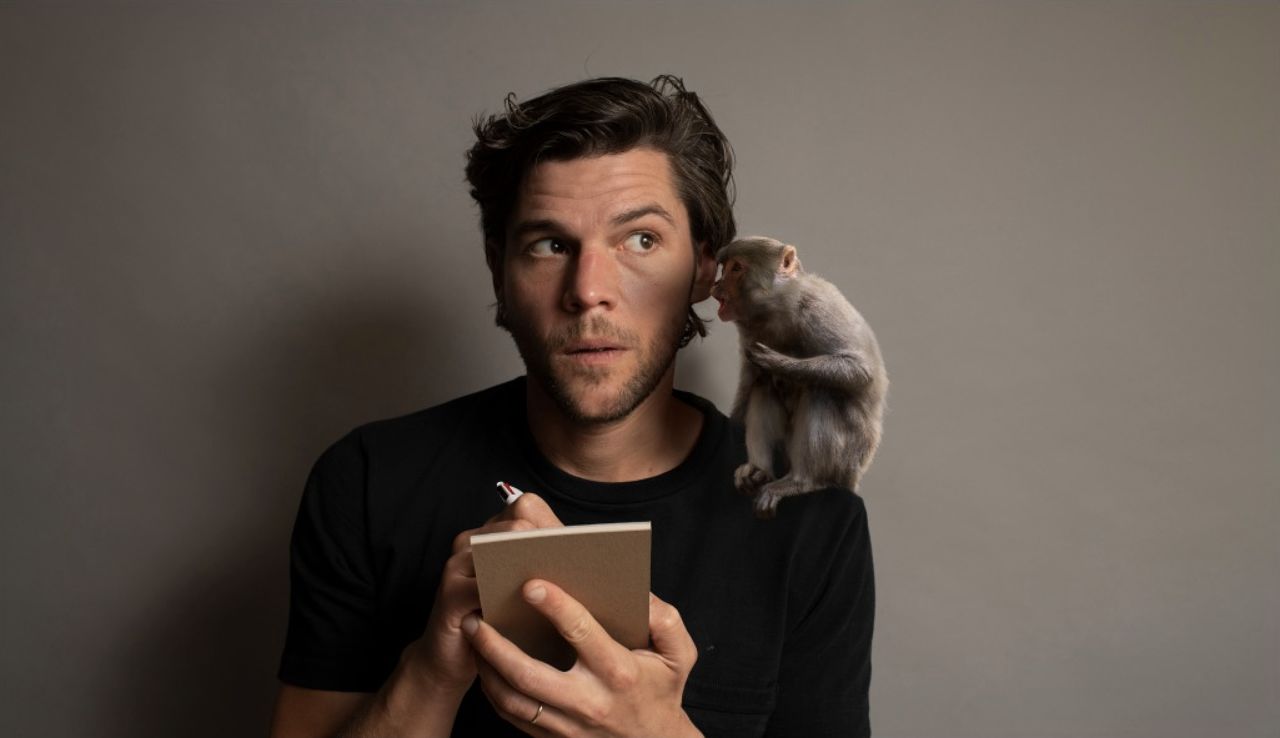

ABOVE: Behind the scenes on Boasty

The essence of Scholfield’s style is in how he wields the camera, the choreography of movements that amplify and expand the choreography of dancers, communicating emotion and narrative through a shooting script in constant motion, where the camera becomes one of the players. “There’s a certain musicality to visuals,” he says. “You should have peaks and troughs, falls and turns. Not that they necessarily correspond with the peaks and troughs in the music, though sometimes it works if they do.”

There’s a way to connect the camera to the scene that can make the audience lean forward.

In Boasty, the camera is a roving witness, prime mover, and the eyes of the audience, as well as another moving body in the mix, an actor with a lens swiping through scenes, getting swept aside, knocked back, plunging through walls into new scenes and scenarios that come and go to the rhythm of the track. “I like the camera to be an active observer. There’s a way to connect the camera to the scene that can make the audience lean forward,” he says. “It lets you feel very present. You feel you are the camera. You’re engaged. People can get obsessed with showing spectacle, and not enough on the performance, which is the real spectacle.”

Getting that performance – from the star, from the dancers, from the crew, from actors – is all about listening, says Scholfield. “You better listen, by which I mean also watch – 50% of listening is body language. You’re listening to what they’re saying and feeling out what is right for them – because when you find what’s right for them, it works so much better.”

Credits

View on-

- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a shots membership

Credits

View on- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

Explore full credits, grab hi-res stills and more on shots Vault

Credits

powered by- Production Company Caviar/London

- Director Henry Scholfield

When it came to prepping Stormzy’s Vossi Bop video, opening on a deserted Westminster Bridge and spinning out from there to take in Ubers, Boris bikes, warehouse wastelands and nightclub bathrooms, star and director worked closely from the start. “That’s where you get videos that feel like they really connect to the track. You and the artist working together to make something visually coherent with the sound they have already created. That, for me, is the best way to work.”

Choreography is central to Scholfield’s method. “My mum was a ballet dancer way back, and took me to a lot of shows. I work with a lot of different choreographers, and I’m very particular about which choreographer for which piece. Because, like an artist, they have a particular voice, and just like choosing the perfect DoP you want to match that voice to the piece you’re trying to create.”

For Dua Lipa’s New Rules, he turned to Cuban-American Teresa ‘Toogie’ Barcelo, while its follow-up, IDGAF, featured the work of Marion Motin, who brilliantly brought to life the song’s tug between assertion and surrender, with Lipa and the dancers doubled up and combatively playing out the argument in the singer’s head, more or less an iteration of The Clash’s ageless dilemma – should I stay or should I go?

“You can give Marion a specific emotion and she creates choreography around that, creating a kind of echo of what it feels like, coming through your body. Like if one part of the track makes me feel it is a moment of surrender, you’re creating a movement that resonates with the feeling of surrender – though it should never be an obvious one, but one that projects something a little more abstract.

Choreography is not just dance, it is a narrative.

"You take that word, that idea, and improvise with it and create a movement that feels right for that emotional beat and musical beat. And that becomes a word in a phrase, and a dance phrase is like a written phrase. If you start to put the words in, there’s a coherence and it becomes like poetry. It becomes a piece, basically. You watch it and it has a meaning beyond what you are looking at. There’s a poetic whole strung up around it. It should always carry emotion though it as a thread. Choreography is not just dance, it is a narrative.”

One of his creative collaborators on IDGAF was Stromae, with whom Scholfield made the extraordinary Tous Les Memes video, in which Stromae plays both himself and a female doppelganger, decidedly unhappy with her male counterpart. Scholfield’s scenarios tend to mix in ideas of the double – his video for Will Young’s Losing Myself is comprised entirely of Will lookalikes, reconstructing themselves for the day to come.

“I saw it so clearly,” he remembers of that video’s gestation. “This is a guy who gets up in the morning and deals with all the voices in his head, which are different projections of his own personality, and he has to bring them together in order for him to walk out the door.”

Credits

View on-

- Production Company Partizan/UK

- Director Henry Scholfield

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a shots membership

Credits

View on- Production Company Partizan/UK

- Director Henry Scholfield

- Editing Company Cut+Run/London

- Record Company Sony Music Entertainment/London

- Post Production Rushes

- Editor James Rose

- Director of Photography Marc Gomez del Moral

- Producer Louise Gagen

- Artist Will Young

Explore full credits, grab hi-res stills and more on shots Vault

Credits

powered by- Production Company Partizan/UK

- Director Henry Scholfield

- Editing Company Cut+Run/London

- Record Company Sony Music Entertainment/London

- Post Production Rushes

- Editor James Rose

- Director of Photography Marc Gomez del Moral

- Producer Louise Gagen

- Artist Will Young

It’s a typically intuitive, psychological insight that maps out the video from that first kernel of connection to final cut. And his sources of inspiration are always from the real world.

We have too much computer thinking. Most of the creatives I know, when they’re really coming up with something good, they’re not staring at a screen.

“I don’t watch music videos,” he says. “If you’re drawing inspiration from the same pool as people who have already made it, you’re becoming a Xerox. I look to other places – I still love to go and see installation pieces, abstract art, video art, because walking around seeing something makes your brain breathe better than when you’re sat in front of a computer screen. We have too much computer thinking. Most of the creatives I know, when they’re really coming up with something good, they’re not staring at a screen.”

And his method of choosing who to work with also follows that same intuitive path of what inspires you, what draws you in. “I try to be driven by the artist and the track, just listening to the track and seeing what it brings in to my head I drift, and the music will make me think of something, usually stuff I’ve seen, or read in an article, or it reminds me of a situation. These can be little nuggets, and I try it make it quite emotively connected to the track first, then I’ll dig in and have a look at the artist.

"From there what you’re looking for is to be inspired. What you want to do is let the idea find you.”

)