The funny business of comedy directing

Station Films director Brendan Gibbons is one of the industry’s most renowned comedy directors. His ongoing work for Progressive Insurance has built a series of established characters and, here, he discusses the processes involved in creating the right environment for comedy gold.

When you do auditions with actors, what qualities win you over and what are a red flag?

BG: What’s great is when an actor can reveal what’s going on behind his or her eyes despite what the character is trying to show the world. This lets viewers close the gap and get the joke on their own. On the other hand, a red flag for me is when I feel the acting. Here’s an example – there’s an awkward situation in the scene and a character exits to avoid the awkwardness.

A red flag for me is when I feel the acting.

Jason Alexander was amazing at this in Seinfeld. He would do a little point and pause then go. This move felt real for George Costanza. But it also became a popular go-to, and when I see actors do it in casting, it makes me cringe. That move doesn’t feel authentic; it feels like a choice to copy George Costanza. If it’s an awkward moment and you’re supposed to leave, just leave. Exits are funny. Especially if you trip.

Above: Jason Alexander as George Costanza in Seinfeld.

Having open communication and rapport with actors seems fundamental to getting great performances; can you share any tips about establishing that rapport?

BG: Commercial sets can be tense. I want the actors to be relaxed and in a mental place where they feel like they can create something, not in a stressful place where people are worried about the schedule or the gardeners mowing the lawn across the street or whatever concern just popped up in video village. So, I try to create a little bubble around the actors where they know it’s safe for them to be artists.

We are making pop culture. We have a huge responsibility not to poison the world with bad advertising.

That word feels highfalutin when you’re talking about a TV commercial. But it’s not. We are making pop culture. We have a huge responsibility not to poison the world with bad advertising. So, I’ll let them know that they’re there because they’re really good at what they do. And that we’re all super lucky to be there together doing what we feel we’re supposed to be doing on this earth. That’s even more highfalutin, but it’s true.

A character in a long-form piece has a backstory. Why wouldn’t a character in a 30-second commercial?

It’s damn cool that we get to do this, and I want the actors to start the day with that appreciation. Then I’ll give them each a backstory. A character in a long-form piece has a backstory. Why wouldn’t a character in a 30-second commercial? This is where those vulnerabilities come from. If that doesn’t work, I’ll make fun of them.

Credits

powered by

- Agency In-House

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency In-House

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

- Executive Producer Theresa Darlington

- Creative Director Rob Goldenberg

- Art Director Orly Kirya

- Executive Producer Michelle Towse

- DP Matthew Woolf

- Talent Shaquille O'Neal

Credits

powered by

- Agency In-House

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

- Executive Producer Theresa Darlington

- Creative Director Rob Goldenberg

- Art Director Orly Kirya

- Executive Producer Michelle Towse

- DP Matthew Woolf

- Talent Shaquille O'Neal

Above: Gibbons' worked with Shaquille O'Neal for this wix.com campaign.

What sort of environment do you encourage/foster with actors on set or during rehearsals that lends itself to improv (beyond what’s scripted)? For example, do you encourage them to keep going if they flub lines?

BG: The most important thing is getting to a flow state. Improv isn’t sitting back and letting the actors ad lib. I’m involved in what’s happening as it’s unfolding, feeling the rhythm of the scene and pushing the performances in whatever direction that rhythm needs to go. I don’t like to over rehearse. I want to understand the timings and the structure before we roll, but I don’t want the actors to lose their spontaneity by over doing it.

Improv isn’t sitting back and letting the actors ad lib.

With this in mind, there are no flub lines. There’s a vibe and there are moments we’re going for. And at the end of the day, only one take of everything we do will make it to the final edit. Who’s to say the magic take of that particular part of the script isn’t the one that the actor got 'wrong' on the day? Unless they suddenly break character trying to be funny. That’s childish and selfish. And I’d prefer they leave that to me.

Above: Brendan Gibbons.

In your experience, is it easier to improvise within a comedic scene or a dramatic scene?

BG: My mind tends to go toward what I think is funny, even if what I’m thinking about is serious. That’s not to say I don’t love shooting scenes that are dramatic or poignant. It’s just that if I then begin to improv with the actors, I usually find myself drifting toward trying to make people laugh. So, for dramatic scenes, we’ll work around the edges of the script to find something great, then I’ll usually break the tension with a joke either right before or after we cut. What can I say? I find people pretending to be serious funny. I also find [religious talk show] The 700 Club funny. Those two examples may or may not be the same thing.

For dramatic scenes, we’ll work around the edges of the script to find something great, then I’ll usually break the tension with a joke either right before or after we cut.

Can you give an example of setting up a joke from one of your high-profile spots for an actor?

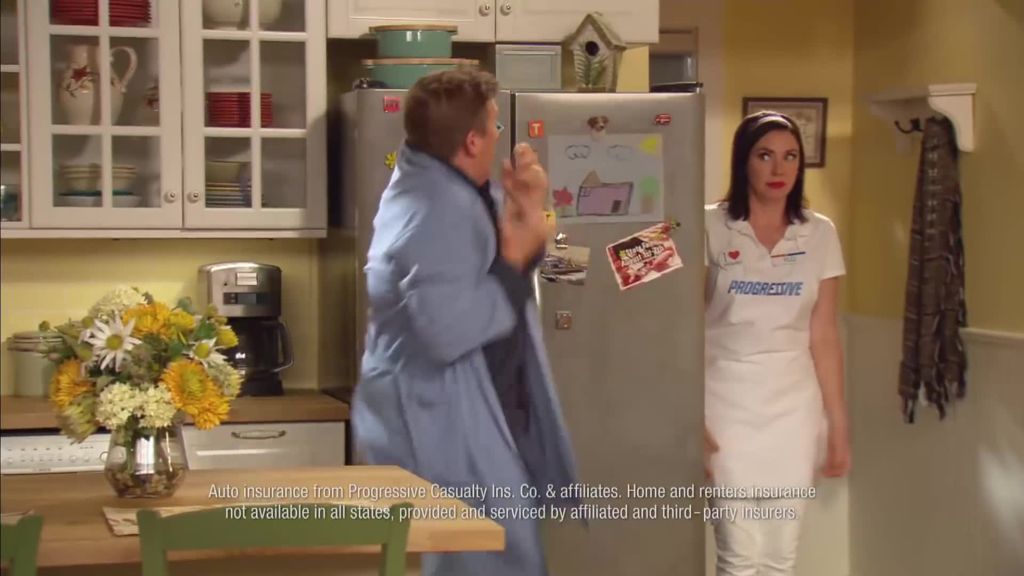

BG: One thing to keep in mind is that it’s not always the joke that gets the laugh. The reaction to the joke is just as important. Jim Cashman, who plays Jamie in the Progressive campaign, is one of the funnier humans you’re gonna meet. Last year we did a spot where it seems as if he’s dating the mom of two teenage boys, who are none too pleased about it.

His response... is a line that I’m not sure we would’ve loved on paper. But coming from Jim, it’s gold. Or at least, silver.

The boys were never meant to actually get upset, but it felt funny in the moment to have one of them scream, “You’re not my dad!” Knowing Jim, I thought he’d react better if he didn’t know what was coming. His response – “That’s fair … overstepped” – is a line that I’m not sure we would’ve loved on paper. But coming from Jim, it’s gold. Or at least, silver.

Above: Gibbons' work for Progressive, which benefitted from some actor improv.

Have you been surprised when a joke that’s very funny on the page misses on camera, and vice-versa?

BG: I’m amazed at directors who know everything they want to do before they actually start doing it. An idea evolves for me. I go pretty deep before the initial agency call, and that opens up a good dialogue about the different opportunities a script has hiding in its white spaces. But this is a collaborative medium, and I find ideas during every step of the process.

Jokes are like Starbucks – you never have to go far to find one.

This is probably a holdover from when I was a copywriter, but when I read a funny script, I don’t laugh. I just think, “That’s funny!”. Maybe that’s a little sad, but writing comedy can make you over-intellectualise the process. But to answer the question – sometimes on set, that same joke doesn’t work, because the page is just the beginning of a collaborative process, and sometimes jokes don’t have the depth to survive that process. Luckily, jokes are like Starbucks – you never have to go far to find one.

Progressive – Progressive Park

Progressive – Maid For Us

Above: More examples of Gibbons' work for Progressive over 2019.

How do your abilities as a visual storyteller and as a comedic performance director complement each other?

BG: I didn’t go to film school. I never thought I could be a director until I was standing there watching a guy direct a spot I’d written thinking, “I’m coming up with better things to tell the actors than he is”. Luckily, I didn’t act on that impulse because this particular director would’ve thrown me in a dumpster. But that belief is what made me want to get into this. Then when you get the chance to actually do it, you realise there’s a thousand other disciplines involved.

Luckily, I didn’t act on that impulse because this particular director would’ve thrown me in a dumpster.

If you’re lucky and driven enough to build a career, you grow into it. Layering those things together is what creates your voice, and that process never stops. The more you know, the more you realise there is to find. I’ll say “find” rather than “learn” because I’m not sure it’s learning. That feels more concrete, like there’s an actual way to go about it. Finding what works for you seems more right. That director became my greatest teacher, by the way. I just haven’t mastered the throwing-the-copywriter-in-the-dumpster part of the process.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Arnold Worldwide

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Arnold Worldwide

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

- Executive Creative Director Sean McBride

- ACD/Copywriter Patrick Franklin

- Senior Art Director Jamie Malnati

- Executive Producer Mike Lawson

- Creative Director Joshua Kahn

- Managing Partner Stephen Orent

- Executive Producer/Partner Caroline Gibney

- Music Company HiFi Project

- Creative Director Nate Donabed

- DP Tim Ives

Credits

powered by

- Agency Arnold Worldwide

- Production Company Station Film

- Director Brendan Gibbons

- Executive Creative Director Sean McBride

- ACD/Copywriter Patrick Franklin

- Senior Art Director Jamie Malnati

- Executive Producer Mike Lawson

- Creative Director Joshua Kahn

- Managing Partner Stephen Orent

- Executive Producer/Partner Caroline Gibney

- Music Company HiFi Project

- Creative Director Nate Donabed

- DP Tim Ives

Above: The Corning.

When you’re directing commercials that parody genres - like Progressive's The Corning or The Seed – is playing the visual genre straight part of the humour?

BG: Every time we’ve gone into a genre we’ve made sure to stay away from parody in the way it’s shot. The idea is to do the thing rather than mimic the thing. The joke is what happens inside of the genre, not in the representation of the genre itself. That means doing things like going to the mat to shoot on film when the idea demands it or using an old arc light that may or may not set the stage on fire (It didn’t).

The joke is what happens inside of the genre, not in the representation of the genre itself.

It also means dumbing it down sometimes, shooting on crappy old cameras for a dated soap opera or after school special look. The more we can do in camera, the closer we get to it feeling like the actual thing. And that lets the absurdity of what the characters are doing create the most tension. It’s also fun. You just have to remember to say, “Cut,” when it’s film. That stuff is expensive.

Above: Gibbons 'Chicago Protocol' does away with small, messy tables.

Do you agree with the adage ‘There are no rules for directing comedy’?

BG: I don’t think there are rules for anything. There are, however, things that have proven to work in the past for me. I’ll stress the “me” part because I have no idea if they work for other people. What I need most is space, both emotionally and physically. I need to be able to let a scene breath to find exactly how and where the comedic tension is peaking.

I need to be able to let a scene breath to find exactly how and where the comedic tension is peaking.

It’s hard to be funny when things are rushed. So, I’ve had to learn to lose my desire to please the people whose job it is to speed things along. Also, I can get a little claustrophobic on a cramped set. I work off of notes on my laptop, which I’m constantly revising. So, the standard director’s monitor tray gets crowded and awkward, and then someone puts their spearmint gum on it and everything goes to hell – I really hate spearmint.

We call it the Chicago protocol since that’s where it was born.

A few years back we were shooting on a basketball court and I realised there was no reason for this ridiculously tiny set up. So, I asked for a six foot table and a low director’s chair. I bring the monitor down to that level then have a huge desk to work with. We call it the Chicago protocol since that’s where it was born. And when we have the space, the Chicago protocol goes into effect. It’s amazing how it frees my mind to play. I also have a lot more room for drinks and snacks. Just don’t put your stupid spearmint gum on it.

)

+ membership

+ membership