The Way I See It: Henry-Alex Rubin

From early gonzo hits like Whopper Freakout to politically charged work for Sandy Hook Promise, SMUGGLER director Henry-Alex Rubin has parlayed his documentarian’s eye into authentic spots that don’t just win gongs (Emmys, Oscar nominations and more) but seek to bring about real change. He tells Selena Schleh about why he makes ads for people who hate ads.

I was born in Boston but moved to Paris when I was 15. My father, an art historian, got a job teaching at the Sorbonne, and he brought the family over there. I was a ‘fac brat’ - a faculty brat – which is someone who lives on campus, usually for free, as the appendage of a professor.

My father also taught at Princeton, Harvard, and SUNY Stony Brook. Wherever he moved, we just picked up and went with him as he climbed the ladder of academia. We never stayed anywhere more than three years, but I loved the way each campus was like a new world. It wasn’t a typical childhood because my dad never threw me a ball. But I could tell you all about Cezanne's apples and pears.

There are hundreds of early tapes of me interviewing my friends and family – my sister found it especially annoying.

As a result, I've grown more than a mere interest in art; I'd say it’s a mild obsession. Particularly from the turn of the century period; the beginnings of modernism and impressionism. I love artists like Toulouse-Lautrec, who were making commercial art like posters to pay the bills. The modern-day equivalent is making ads.

As a kid, I really wanted to be a concert pianist. I gave it up because I didn't have the discipline. I still love classical and contrapuntal music. Today my audience consists mainly of my two-year-old daughter, and instead of Chopin and Bach, it's Baa Black Sheep and Doe a Deer.

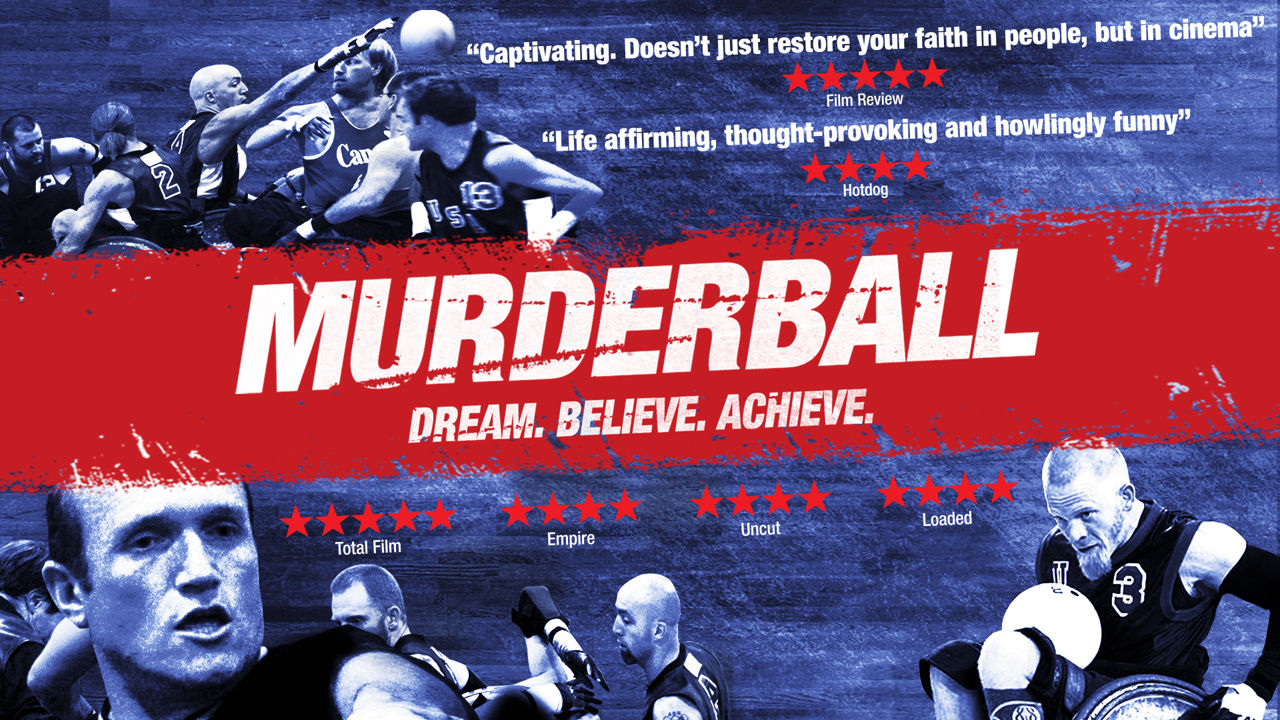

Above: Rubin's 2005 Oscar nominated documentary Murderball follows a group of quadriplegic rugby players, as they compete to land a place in the Paralympic Games.

Although I studied film at Columbia, it was documentaries that I loved. I had a little video camera my father borrowed it from the art department, and from a young age I enjoyed being behind the camera and interviewing people. There are hundreds of early tapes of me interviewing my friends and family – my sister found it especially annoying. It was a nice smoke screen behind which you could ask the sorts of questions that you'd get smacked for if you did it without a camera.

Those ads were like little Molotov cocktails, blasts of rebellious creativity in seconds... those guys were making art under the radar: art paid for by The Man.

Being an artsy kid, I inevitably got bullied. There was one kid who really hated me and would push me in the hallway. One day I decided to interview everybody in his class except for him. The express purpose of this was to make him curious and agree to an interview. When I finally interviewed him, I didn't ask a single thing about why he'd bullied me – I completely sidestepped any animosity between us and we just talked about his life. It was a lovely chat, and we became friends. That showed me the power of the interview.

As a young filmmaker, documentaries seemed the highest form of the art because they were revealing real truths about real people, instead of fake movie stuff. I still love watching them. They help me make sense of the world. I’ve recently watched seven or eight documentaries about the history of Gaza, to try to help me understand the situation.

My big break was Murderball. I’d made several documentaries before that: Freestyle, which was a real labour of love, and Who Is Henry Jaglom?, about an obscure art film director who made movies without scripts – but they had very small, specific audiences. Murderball was nominated for an Oscar, which was a giant head swirl. That's when several commercial production companies asked me if I was interested in directing commercials.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Miami

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Miami

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- CD Rob Reilly

- CD Bill Wright

- ACD/Writer Ryan Kutscher

- Sr AD Paul Caiozzo

- Art Director Andy Minisman

- Art Director Daniel Treichel

- Art Director Julia Hoffman

- Copywriter Omid Farhang

- Copywriter Nathan Dills

- Exec Producer Chris Kyriakos

- HP David Rolfe

- Exec Producer Patrick Milling-Smith

- Exec Producer Brian Carmody

- Exec Producer Lisa Rich

- Editor Adam Pertofsky

- Editor Chan Hatcher

- Editor Matthew Murphy

- Music Amber Music

- DP Learan Kahanov

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Miami

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- CD Rob Reilly

- CD Bill Wright

- ACD/Writer Ryan Kutscher

- Sr AD Paul Caiozzo

- Art Director Andy Minisman

- Art Director Daniel Treichel

- Art Director Julia Hoffman

- Copywriter Omid Farhang

- Copywriter Nathan Dills

- Exec Producer Chris Kyriakos

- HP David Rolfe

- Exec Producer Patrick Milling-Smith

- Exec Producer Brian Carmody

- Exec Producer Lisa Rich

- Editor Adam Pertofsky

- Editor Chan Hatcher

- Editor Matthew Murphy

- Music Amber Music

- DP Learan Kahanov

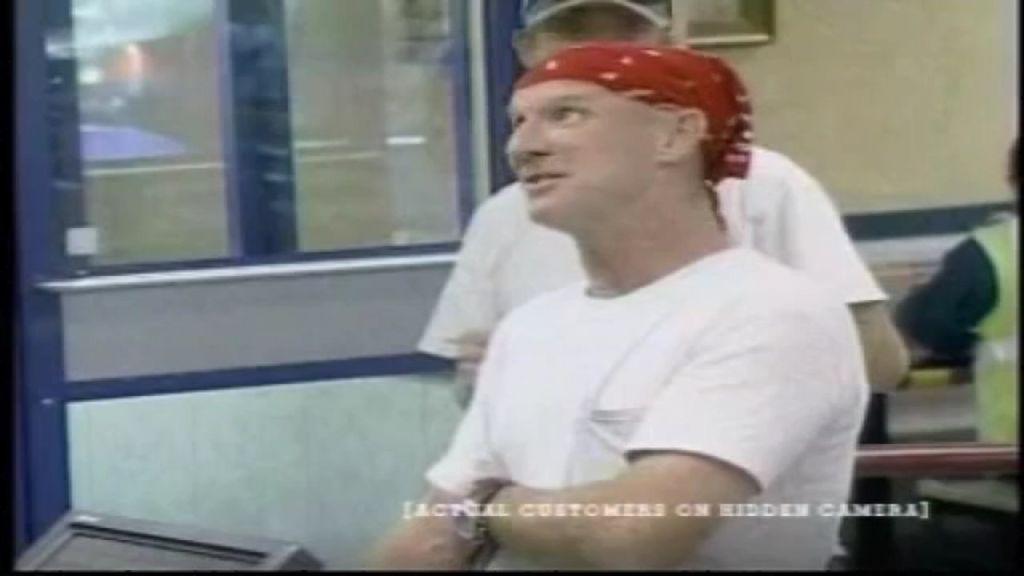

Above: Rubin was fired for an hour while working with Rob Riley on Whopper Freakout, as tensions ran high over client unease.

I’d grown up hating ads. As a child, I remember muting horrible commercials like Hubba Bubba’s Big Bubbles, No Troubles!. But one of the people that approached me was [SMUGGLER co-founder] Patrick Milling Smith, and he showed me the work of Jonathan Glazer and Frank Budgen. I’d never seen anything like it before. Those ads were like little Molotov cocktails, blasts of rebellious creativity in seconds. And the idea that a company was paying for this almost felt subversive, like those guys were making art under the radar: art paid for by The Man. So that changed my mind. Ever since then, I’ve been trying to make ads for people who hate ads.

When I made Murderball with my friend Dana [Adam Shapiro], we were a crew of two: he held the mic and I held the camera.

I joined Smuggler in the very early days, around 17 years ago, when there were only eight of us. They didn't have any documentary filmmakers [on the roster] and Patrick felt like it would be an interesting mix to have someone coming from a documentary background. We were the back beats of the commercial industry back then. We had to fight for every job and our budgets were tiny – although coming from a documentary background, I didn’t see it that way. When I made Murderball with my friend Dana [Adam Shapiro], we were a crew of two: he held the mic and I held the camera. The first time I saw a budget for a commercial, I looked at all the money and I couldn't understand how to spend it.

What was I like in the early days of my career? Well, being a dick wasn’t an option. That’s for people who think that’s how directors are supposed to behave because they see it in movies – being stubborn and uncompromising to everybody around you because you’re so brilliant. I tried to be collaborative from the beginning, because I definitely didn’t know what I was doing.

Crispin Porter Bogusky was my ad school. I worked closely with Alex Bogusky on a bunch of spots for Burger King and Volkswagen, and although he never really explained anything to me, he always treated me like an equal. We would have good philosophical chats about what the job was about, and then he would say, “Go do it.”

CPB were renegades and I was a little rascal, so it was a match made in heaven.

I had a producer who was so old school, he would literally ‘palm’ money to people to get things done. Sadly, you can't do that anymore, everything has to be signed and sealed. But it was the early days and we were just making shit up; we did a lot of uninsured things that would never fly anymore. CPB were renegades and I was a little rascal, so it was a match made in heaven.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Boulder

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Boulder

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- ACD Matt Denyer

- ACD Crispin Porter Bogusky/Boulder

- Art Director Andrew Lincoln

- CD Mark Moll

- CD Tony Calcao

- Copywriter Matt Talbot

- Producer Integrated Julie Vosburgh

- Music Black Iris Music

- Sound Design Loren Silber

- Animator The Wilderness

- Colorist Siggy Ferstl

- Exec Producer Lisa Rich

- Post Method Studios/Los Angeles

- Editor Chan Hatcher

- Editor Dan Aronin

- Line Producer Drew Santarsiero

- DP Darren Lew

Credits

powered by

- Agency Crispin Porter Bogusky/Boulder

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- ACD Matt Denyer

- ACD Crispin Porter Bogusky/Boulder

- Art Director Andrew Lincoln

- CD Mark Moll

- CD Tony Calcao

- Copywriter Matt Talbot

- Producer Integrated Julie Vosburgh

- Music Black Iris Music

- Sound Design Loren Silber

- Animator The Wilderness

- Colorist Siggy Ferstl

- Exec Producer Lisa Rich

- Post Method Studios/Los Angeles

- Editor Chan Hatcher

- Editor Dan Aronin

- Line Producer Drew Santarsiero

- DP Darren Lew

Above: Domino's initially hated the concept of Pizza Turnaround, which forced them to admit their product had previously tasted "like shit".

Rob Riley [now WPP’s Global Chief Creative Officer] taught me a few things. He was the head creative under Bogusky at that time, and we butted heads a bunch of times – especially on Whopper Freakout. I was pushing it a little too far to get people’s reactions, and the client was getting uncomfortable and told Rob to tell me to stop. Of course, I ignored him; why would a client tell me about filmmaking?

Alex [Bogusky] told Domino's: “I'm telling you that if you air this ad, you will win the pizza wars."

No one had explained the protocols to me. According to my producer Drew, I was fired for an hour, but I didn’t hear about that till afterwards, so I just kept going – and we eventually did get someone to freak out. The spot ended up great and Rob and I went on to do a lot of work together. Of course, he still denies that he fired me.

Alex Bogusky didn't give a fuck about what anybody thought, and that was inspiring. When we made Domino's Pizza Turnaround [in which top-tier Domino’s employees confront negative feedback from the public] I was given permission to interview the CEO and the CMO, and the gist of the interview was: most people think Domino’s pizza tastes like shit, like tomato ketchup over cardboard. The punchline of the whole campaign was that Domino’s had a new recipe: ‘We know we used to suck, but we don’t anymore!’

It was another example of a project where I didn't quite understand corporate America yet. I didn't realise how unsettling it would be to get those people to actually acknowledge [the reality] – and they absolutely hated the ad at first. But I remember Alex telling them: “I don’t care if you want to fire us. We have other clients who will listen to me. But I'm telling you that if you air this ad, you will win the pizza wars. And if you don't, you'll keep losing.” I'd never heard anyone speak like that to a client before. Domino’s went ahead and aired it – on a small scale at first – and of course, their stock skyrocketed.

I don't think there's many Boguskys out there anymore, but there are some very courageous agencies like David, Gut and Mischief, who remind me of the early days of CPB.

Above: Jonathan Glazer's celebrated 2000 ad for Wrangler, Ride, has been an inspiration for Rubin.

Wrangler Ride by Jonathan Glazer is the spot that made me think: OK, wait – ads can be exciting. It’s full of these incredibly striking moments, whether it's a rattlesnake biting the camera or a house on fire, or snow hitting the lens. Paul Rayburn from Soundtree is a genius for putting Follow the Yellow Brick Road [from The Wizard of Oz] over it. ‘Authentic’ is a word that gets thrown around so much, but if you want to see something that looks and feels real, watch that spot.

The ad which is the perfect merger of me as a documentary filmmaker and some fictional elements is Gatorade’s Made in NY. It’s an ad but it's also a time capsule. It’s a little documentary: real, but planned. Derek [Jeter] and I plotted it all out: how his last day on the job should look and feel, from the moment he gets out of the car and decides to walk eight blocks to the stadium. I had documentary cameras everywhere: following him, coming out of hiding places, up on bridges. I’d cast real people, but they didn't know they were going to see Derek – they just thought they were going to be in a humdrum Gatorade spot celebrating the Yankees.

Trojan horsing bigger themes and ideas into commercials can be really illuminating.

At some point it became this Pied Piper scene where there was such a huge crowd around us, you can see the bodyguards I hired to help manage people are actually in shot. And when Derek goes downstairs into the dugout and looks at his shirt number, 2 - which is being retired with him – it’s the perfect hybrid of fiction and a moment in history. He told me that he would walk past the pit all the time and never really look at the shirts, but when I asked him to do that, it created a really profound moment for the fans.

Emotion is something that I try to search for in every spot, even something as seemingly superficial as Bullying Jr for Burger King, where we staged a fake bullying scene in Burger King, and watched with hidden cameras [to see] who would ignore it and who would stand up for the kid. That had nothing to do with burgers. It had to do with humanity. Trojan horsing bigger themes and ideas into commercials can be really illuminating.

The best single day of my career was winning an Emmy for Sandy Hook Promise Teenage Dream on my birthday.

The worst day of my career was finding out that my dear friend, Dave Devlin, an incredible DP and a true artist, had slipped in the shower and died. We’d travelled the world and shot over a hundred ads together, and I found out the day before he was supposed to do my next job. I’m still not over the fact he passed in such an absurd way.

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWA Chiat Day/Los Angeles

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWA Chiat Day/Los Angeles

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Chief Cr Off Stephen Butler

- Copywriter Nick Ciffone

- Art Director Dave Estrada

- Exec Producer Sarah Patterson

- Assistant Producer Garrison Askew

- Exec CD Brent Anderson

- CD Renato Fernandez

- DP Enrique Chediak

- Editor Damion Clayton

- Exec Producer Lisa Tauscher

- MD Peter Ravailhe

- Song "My Way" Frank Sinatra

- Talent Derek Jeter

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWA Chiat Day/Los Angeles

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Chief Cr Off Stephen Butler

- Copywriter Nick Ciffone

- Art Director Dave Estrada

- Exec Producer Sarah Patterson

- Assistant Producer Garrison Askew

- Exec CD Brent Anderson

- CD Renato Fernandez

- DP Enrique Chediak

- Editor Damion Clayton

- Exec Producer Lisa Tauscher

- MD Peter Ravailhe

- Song "My Way" Frank Sinatra

- Talent Derek Jeter

Above: Rubin sees the Gatorade spot, Made in NY, as a "little documentary: real, but planned."

The most important lesson that I’ve learned during my time in the industry is that you really have to listen to your instinct, because it's what's usually gotten you to the place you're at. In advertising there's a million people trying to bend your thinking towards their agendas, from your crew to the creatives to the client, so you have to listen to everybody and then just quietly do what you think is right. Although it’s hard when you have the sort of personality where you want to listen to everyone – I'm like my mother, who’s the kind of person that always pulls up another chair at the table.

I've met some wild egos in the film industry, but in the commercial world, everyone has a pretty good sense that they're not curing cancer.

It’s interesting having one foot in the advertising world and one in independent cinema. I've met some of the biggest jerks and wildest egos in the film industry, but in the commercial world, everyone has a pretty good sense that they're not curing cancer. In the movie business, you're only as good as your last film, which is luckily not true of advertising. You can make a few off spots, and everybody gives you a pass because they know it probably wasn’t your fault. It was the client that forced you to use the ‘N Sync track.

Awards? I don’t really think about that stuff. [Work that leads to] signatures on a petition for legislation to support kids’ online safety [Dove Cost of Beauty] or helps thwart over a thousand school shootings [Sandy Hook Promise], that’s what’s rewarding. My mentor Jim Mangold, who has one of the greatest careers as a Hollywood director, jokingly calls me ‘Goldfinger’ because of all the ad awards I’ve won and I call him ‘Mangoldfinger’ because of all his Oscar wins and nominations. The difference, I said, is that nobody cares about ads, to which he says “anything well done can have majesty.

I'll do two or three PSAs a year to break up my schedule from the paychecks: something useful so that it balances out the karma.

PSAs don’t pay well, but for me, they’re a really important part of commercial filmmaking. Coming from documentaries, I have a deep, overwhelming urge to try to do something good with this skillset – in the same way that lawyers do pro bono work. Since I’ve been at SMUGGLER, both Brian [Carmody] and Patrick have impressed on me: that I can still use the skills that I love from my documentary world – for good.

I'll do two or three PSAs a year to break up my schedule from the paychecks: something useful so that it balances out the karma, or whatever you want to call that guiding force that envelopes us all. Whether that’s films about gun control, child abuse, texting and driving, even some pro-vaccine campaigns, I feel I have a responsibility to make things that could potentially effect change. Of course, I love to make a fun ad and get paid for it. But if you do too many of those in a row, without a more personal cause, you start losing your north star.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Ogilvy/London

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Ogilvy/London

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Editorial Final Cut/New York

- Post Production Significant Others

- Color Color Collective

- Audio Machine Sound/New York

- Music Big Sync Music/USA

- Post Production Coffee & TV

- Executive Creative Director Daniel Fisher

- Chief Creative Officer Francesco Grandi

- Associate Creative Director Copy Morgan Starr

- Associate Creative Director Art Luke Woodard

- Head of Integrated Production James Brook-Partridge

- Lead Senior Film Producer Amanda Kresge

- Head of Production Chris Chapman

- Co-Founder Patrick Milling-Smith

- Co-Founder Brian Carmody

- Executive Producer/Managing Director Fergus Brown

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Line Producer Manny Caston

- DP David Devlin

- 1st Assistant Director Ed Walsh

- Production Designer Justin Allen

- Wardrobe Stylist Callan Stokes

- Co-Editor Ashley Kreamer

- Co-Editor Jim Helton

- Assistant Editor Chris Rizzo

- Senior Producer Wade Weliever

- Head of Production Penny Ensley

- Executive Producer Sarah Roebuck

- Managing Director Justin Brukman

- Executive Creative Director Dirk Greene

- Lead Flame Phil Apostol

- Head of Design Phil Brooks

- Senior Producer Jen Tremaglio

- Producer Kyla Amols

- Executive Producer Alyssa St Vincent

- Senior Colorist Alex Jimenez

- Executive Producer Claudia Guevara

- Executive Producer Matej Oreskovic

- Sound Designer & Mix Alex Bingham

- Audio Assistant Chas Langston

- Additional Music Patrick Burniston

- Music Supervisor Alexandra Carlsson Norlin

- Producer Gus Quirk

- Creative Director Steve Waugh

- CGI artist Ben Cantor

- CGI Artist Adam Lindsey

- 2D artist Jess Gorick

- Senior Designer Laurence Blake

Credits

powered by

- Agency Ogilvy/London

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Editorial Final Cut/New York

- Post Production Significant Others

- Color Color Collective

- Audio Machine Sound/New York

- Music Big Sync Music/USA

- Post Production Coffee & TV

- Executive Creative Director Daniel Fisher

- Chief Creative Officer Francesco Grandi

- Associate Creative Director Copy Morgan Starr

- Associate Creative Director Art Luke Woodard

- Head of Integrated Production James Brook-Partridge

- Lead Senior Film Producer Amanda Kresge

- Head of Production Chris Chapman

- Co-Founder Patrick Milling-Smith

- Co-Founder Brian Carmody

- Executive Producer/Managing Director Fergus Brown

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Line Producer Manny Caston

- DP David Devlin

- 1st Assistant Director Ed Walsh

- Production Designer Justin Allen

- Wardrobe Stylist Callan Stokes

- Co-Editor Ashley Kreamer

- Co-Editor Jim Helton

- Assistant Editor Chris Rizzo

- Senior Producer Wade Weliever

- Head of Production Penny Ensley

- Executive Producer Sarah Roebuck

- Managing Director Justin Brukman

- Executive Creative Director Dirk Greene

- Lead Flame Phil Apostol

- Head of Design Phil Brooks

- Senior Producer Jen Tremaglio

- Producer Kyla Amols

- Executive Producer Alyssa St Vincent

- Senior Colorist Alex Jimenez

- Executive Producer Claudia Guevara

- Executive Producer Matej Oreskovic

- Sound Designer & Mix Alex Bingham

- Audio Assistant Chas Langston

- Additional Music Patrick Burniston

- Music Supervisor Alexandra Carlsson Norlin

- Producer Gus Quirk

- Creative Director Steve Waugh

- CGI artist Ben Cantor

- CGI Artist Adam Lindsey

- 2D artist Jess Gorick

- Senior Designer Laurence Blake

Above: Dove's Cost of Beauty campaign inspired over 65,000 people to sign a petition advocating for mental wellness in children affected by harmful beauty standards.

Documentaries are rooted in the trust that you have with your subjects. Fiction and commercials are much more regimented: the atmosphere of the set creates an instantly false atmosphere where everyone is ‘performing’. I love trying to break down those contrivances. In every ad, being able to elicit a real emotion is always a cherished opportunity. I will schedule an entire day around capturing the right moment.

I’d asked the mom to sing the song we were going to use over the film, You Are So Beautiful, to her daughter. It was a really emotional moment to capture.

I love working with real people because I can usually make them comfortable enough to just be themselves – I’m always plotting how to get people not to ‘act’. Because the gaze of the entire crew is on the subject, it’s very intrusive, so I've had to find ways to make them feel they’re alone with me. On The Cost of Beauty for Dove, I moved the cameras way back and used a long lens. Almost on a lark, I’d asked the mom to sing the song we were going to use over the film, You Are So Beautiful, to her daughter. It was a really emotional moment to capture – just me, sitting on a crane, and the two of them. I don't think she would have sung it if she’d seen a single crew member.

As a documentary filmmaker, I live by the mantra ‘ABS’. ‘Always be shooting’ - but pretend to be doing it only 50 per cent of the time.

The best advice I’ve ever been given was from my mother, who always says: If you see the best in people, you'll have a happy life.” It’s a lifelong effort to block out cynicism and seeing the flaws in the situation or people – because it’s so much easier to see what’s wrong. But once you start looking, you can always find something beautiful.

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBDO/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBDO/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Chief Creative Officer David Lubars

- Executive Creative Director Peter Alsante

- Creative Director Jim Connolly

- HP Alex Gianni

- Producer Molly Ross

- Senior Music Producer Julia Millison

- Executive Producer Patrick Milling-Smith

- Executive Producer Brian Carmody

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Head of Production Alex Hughes

- Associate Producer Leah Fleischmann-Allina

- DP David Devlin

- Edit /Conform/Finishing Company Mackcut

- Executive Producer Gina Pagano

- Editor Ian Mackenzie

- Assistant Editor Cooper McLane

- Lead Flame Artist Jimmy Hayhow

- Interview Editor Franklin Ponce

- Interview Editor Mike Leuis

- Colorist Alex Bickel

- Executive Producer Claudia Guevara

- Music Company Human Music & Sound Design/USA

- Creative Lead/Chief Engineer Sloan Alexander

- Executive Producer James Dean Wells

- Arranger Sloan Alexander

- Associate Producer Mark Perez

- Line Producer Catalina Restrepo

Credits

powered by

- Agency BBDO/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Chief Creative Officer David Lubars

- Executive Creative Director Peter Alsante

- Creative Director Jim Connolly

- HP Alex Gianni

- Producer Molly Ross

- Senior Music Producer Julia Millison

- Executive Producer Patrick Milling-Smith

- Executive Producer Brian Carmody

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Head of Production Alex Hughes

- Associate Producer Leah Fleischmann-Allina

- DP David Devlin

- Edit /Conform/Finishing Company Mackcut

- Executive Producer Gina Pagano

- Editor Ian Mackenzie

- Assistant Editor Cooper McLane

- Lead Flame Artist Jimmy Hayhow

- Interview Editor Franklin Ponce

- Interview Editor Mike Leuis

- Colorist Alex Bickel

- Executive Producer Claudia Guevara

- Music Company Human Music & Sound Design/USA

- Creative Lead/Chief Engineer Sloan Alexander

- Executive Producer James Dean Wells

- Arranger Sloan Alexander

- Associate Producer Mark Perez

- Line Producer Catalina Restrepo

Above: The gun violence PSA for Sandy Hook Promise. Rubin feels he has a responsibility to use his skillset to make things that could potentially effect change.

This may sound ridiculous, but the person that I most admire musically is Bach, and at the end of his life he wrote a final fugue. It's one of the most beautiful things I've ever heard – but it just stops, right in the middle. I'd love to go back in time and tell him he's going to die, so to hurry up and finish it.

My biggest fear? Making cheesy ads.

My biggest regret is saying no when Forsman & Bodenfors asked me to direct Volvo Epic Split. Whoopsie.

The production industry has changed so much from when I started out – especially from a technology standpoint, so many tools that didn’t exist before like large format video sensors, drones and generative AI. There’s a general democratisation within the landscape: anyone can make something and get it seen. The aperture of opportunities has widened. That said, I think hard work, collaboration with others and a curious mind are still the seeds to success.

The advice I’d give a young director now is: make films on your phone. Don't worry about a crew, don’t worry about waiting to get everything lined up or you'll always be waiting.

My biggest regret is saying no to my friends at Forsman & Bodenfors when they asked me to direct Volvo Epic Split. Whoopsie.

Credits

powered by

- Agency FCB/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency FCB/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Co-Founder Brian Carmody

- Co-Founder Patrick Milling-Smith

- Managing Director Sue Yeon Ahn

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Head of Production Alex Hughes

- Editing Whitehouse Post/New York

- Executive Post Producer Ryan Smith / (Executive Post Producer)

- Head of Production Eric Schoen

- Editor Russell Icke

- Assistant Editor Paul Rummerfield

- Post Production The Mill/New York

- Senior Executive Producer Chris Connolly

- Executive Creative Director Gavin Wellsman

- VFX Supervisor Renato Carone

- Colorist Paul Yacono

- Music Arrangement/Music Licensing Barking Owl

- Executive Music Producer Ashley Benton

- Junior Music Producer Jenna Pangilinan

- Music Creative Director Kelly Bayett

- Music Creative Director Johanna Cranitch

- Sound Sonic Union

- Head of Sound Production Patrick Sullivan / (Head of Production)

- Sound Designer/Audio Mixer Steve Rosen

- Sound Designer Kelly Oostman

- Chief Creative Officer Michael Aimette

- Global Creative Partner Danilo Boer

- Group Creative Director Alexandre Abrantes

- Creative Director Laszlo Szloboda

- Creative Director Daniel Grech

- Creative Director Jason Gorman

- Line Producer Arlene McGann

- Associate Creative Director Lara Polovina

- Associate Creative Director David Green

- DP Pat Scola

- Production Designer Laura Fox

- HP Nick Williams

- Executive Integrated Producer Daniel Roversi

- Executive Producer Marissa Lando

- Song "The Weight" The Band

- Composer Jacob Plasse

Credits

powered by

- Agency FCB/New York

- Production Company SMUGGLER

- Director Henry-Alex Rubin

- Co-Founder Brian Carmody

- Co-Founder Patrick Milling-Smith

- Managing Director Sue Yeon Ahn

- Executive Producer Drew Santarsiero

- Head of Production Alex Hughes

- Editing Whitehouse Post/New York

- Executive Post Producer Ryan Smith / (Executive Post Producer)

- Head of Production Eric Schoen

- Editor Russell Icke

- Assistant Editor Paul Rummerfield

- Post Production The Mill/New York

- Senior Executive Producer Chris Connolly

- Executive Creative Director Gavin Wellsman

- VFX Supervisor Renato Carone

- Colorist Paul Yacono

- Music Arrangement/Music Licensing Barking Owl

- Executive Music Producer Ashley Benton

- Junior Music Producer Jenna Pangilinan

- Music Creative Director Kelly Bayett

- Music Creative Director Johanna Cranitch

- Sound Sonic Union

- Head of Sound Production Patrick Sullivan / (Head of Production)

- Sound Designer/Audio Mixer Steve Rosen

- Sound Designer Kelly Oostman

- Chief Creative Officer Michael Aimette

- Global Creative Partner Danilo Boer

- Group Creative Director Alexandre Abrantes

- Creative Director Laszlo Szloboda

- Creative Director Daniel Grech

- Creative Director Jason Gorman

- Line Producer Arlene McGann

- Associate Creative Director Lara Polovina

- Associate Creative Director David Green

- DP Pat Scola

- Production Designer Laura Fox

- HP Nick Williams

- Executive Integrated Producer Daniel Roversi

- Executive Producer Marissa Lando

- Song "The Weight" The Band

- Composer Jacob Plasse

Above: This nostalgic Big Game spot starred the iconic Budweiser Clydesdales in their 46th Super Bowl appearance.

The closest I’ve been to death was 10 years ago, when I was hit from behind while riding my motorcycle. I woke up in hospital and I couldn’t speak for a few hours. It definitely jumbled my brain a little bit, but I think for the better.

What makes me angry? Politics. I’m also very protective of my crew: from my favourite AD, to the sound person and wardrobe, they're all friends and I’ve been working with some of them for over 17 years. So when an outsider comes in and starts making things difficult, I won't stand for it.

Have a couple of fingers of red wine with your dinner and mind your own business.

If I was US President for the day, I’d start by ratifying the ERA [the Equal Rights Amendment]. Equal rights seem like a no brainer. But the fact is, that it doesn’t really matter who’s the president – they’re not the person who wields the power. We’re talking about governments, and we should be talking about corporations.

My ambition is to learn the entirety of the Goldberg Variations.

At the end of the day, what really matters? I’ll borrow the answer to that from the oldest woman alive, who’s 116. Have a couple of fingers of red wine with your dinner and mind your own business.

)

+ membership

+ membership