The Way I See It: James Sorton

James Sorton, MD & EP of multi-award-winning Pulse Films, which bagged a stash of Lions this year, including a Film Grand Prix, shares with Carol Cooper his thoughts on Pulse’s early ambitions, the human texture of IRL working, and the freedom of a childhood full of Far Eastern promise.

I’m really proud of the work we’ve produced in the last couple of years and, after success at the British Arrows and shots Awards, I was feeling optimistic about Cannes. Pulse has consistently backed and developed our talent for long-term success, so coming away from the Lions with a Grand Prix (for Nike’s You Can’t Stop Us), and as the second-most awarded production company at the festival, feels incredible and very motivating for the future.

Advertising is an amazing art form, and I'm glad it's celebrated as it is. The people you work with; the craftsmanship that goes into it, we're so lucky, we really are.

I recall thinking when I was a boy that whatever job I did, I just didn’t want to wear a suit.

I missed being at Cannes in person. So much of it is about celebrating the work together. It’s the one time of the year when you get to be with all the people you've been working with, buddies from different countries, service companies etc. Those in-person physical connections are vital. This business is so much about that. I’ve met some incredible people there and had some great experiences. It's been a big part of my career.

Advertising wasn't always something I wanted to go into. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I recall thinking when I was a boy that whatever job I did, I just didn’t want to wear a suit.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Wieden + Kennedy/Portland

- Production Company Pulse Films/USA

- Director Oscar Hudson

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Wieden + Kennedy/Portland

- Production Company Pulse Films/USA

- Director Oscar Hudson

- Creative Director Eric Baldwin

- Executive Creative Director Alberto Ponte

- Executive Creative Director Ryan O'Rourke

- Copywriter Dylan Lee

- Art Director Naoki Ga

- Associate Producer Shani Storey

- Associate Producer Samson Selam

- Director of Production Matt Hunnicutt

- Executive Producer Jake Grand

- Executive Producer Krystle Mortimore

- Senior Producer Katie McCain

- Senior Producer Byron Oshiro

- Sound Design Joint Editorial (In-House at Wieden + Kennedy)

- Managing Director Hillary Rogers

- Executive Producer Davud Karbassioun

- Executive Producer Darren Foldes

- Editing Company Joint Editorial (In-House at Wieden + Kennedy)

- Editor Peter Wiedensmith

- Executive Producer Leslie Carthy

- Assistant Audio Mixer Natalie Huizenga

- Sound Designer/Audio Mixer Noah Woodburn

- VFX Company a52

- Executive Producer Patrick Nugent

- VFX Supervisor Patrick Murphy / (VFX Supervisor)

- Managing Director Jennifer Sofio Hall

- Executive Producer Kim Christensen

- VFX Producer Everett Cross

- VFX Producer Andrew Rosenberger

- CG Supervisor Andy Wilkoff

- Color Company Primary/Los Angeles

- Colorist Daniel de Vue

- Executive Producer Thatcher Peterson

- Creative Director Jason Bagley

- DP Logan Triplett

- Production Designer Adam William Wilson

- Editor Jessica Baclesse

- VFX Producer Jillian Lynes

- Talent Larry Fitzgerald

- Talent LeBron James

- Talent Colin Kaepernick

- Talent Megan Rapinoe

- VO Megan Rapinoe

- Talent Serena Williams

- Talent Venus Williams

- Talent Russell Wilson

Credits

powered by

- Agency Wieden + Kennedy/Portland

- Production Company Pulse Films/USA

- Director Oscar Hudson

- Creative Director Eric Baldwin

- Executive Creative Director Alberto Ponte

- Executive Creative Director Ryan O'Rourke

- Copywriter Dylan Lee

- Art Director Naoki Ga

- Associate Producer Shani Storey

- Associate Producer Samson Selam

- Director of Production Matt Hunnicutt

- Executive Producer Jake Grand

- Executive Producer Krystle Mortimore

- Senior Producer Katie McCain

- Senior Producer Byron Oshiro

- Sound Design Joint Editorial (In-House at Wieden + Kennedy)

- Managing Director Hillary Rogers

- Executive Producer Davud Karbassioun

- Executive Producer Darren Foldes

- Editing Company Joint Editorial (In-House at Wieden + Kennedy)

- Editor Peter Wiedensmith

- Executive Producer Leslie Carthy

- Assistant Audio Mixer Natalie Huizenga

- Sound Designer/Audio Mixer Noah Woodburn

- VFX Company a52

- Executive Producer Patrick Nugent

- VFX Supervisor Patrick Murphy / (VFX Supervisor)

- Managing Director Jennifer Sofio Hall

- Executive Producer Kim Christensen

- VFX Producer Everett Cross

- VFX Producer Andrew Rosenberger

- CG Supervisor Andy Wilkoff

- Color Company Primary/Los Angeles

- Colorist Daniel de Vue

- Executive Producer Thatcher Peterson

- Creative Director Jason Bagley

- DP Logan Triplett

- Production Designer Adam William Wilson

- Editor Jessica Baclesse

- VFX Producer Jillian Lynes

- Talent Larry Fitzgerald

- Talent LeBron James

- Talent Colin Kaepernick

- Talent Megan Rapinoe

- VO Megan Rapinoe

- Talent Serena Williams

- Talent Venus Williams

- Talent Russell Wilson

Above: Nike's You Can't Stop us, produced bby Pulse, won a Film Grand Prix at the Cannes Lions last week.

I grew up in Hong Kong. My parents moved out there in 1976 and I was born there in 1978.

My dad's a civil engineer, and my mum's a nurse. Dad got offered a job in Hong Kong just after meeting her. So, they got married something like three months after meeting, jumped on a plane and moved out to Hong Kong, never having visited there. Which I think is pretty extraordinary.

Apart from a two-year stint back in the UK, in the Lake District, we lived in Hong Kong till I was 12 or 13. I went to an international school. It was fun; so diverse; so open and welcoming. When I came to England I really noticed how different I was. Hong Kong has really kind of stayed with me, maybe because I was born there. The smell of it, the energy; the atmosphere. I used to get real pangs of homesickness for it.

When I came to England I really noticed how different I was.

I did ballet when I was a kid and I was quite good. I would dance with the Hong Kong Ballet every Christmas. They asked me to join their youth school but I wasn’t taking it seriously, so I said no. When we moved back to England, my mom suggested I continue with ballet. And I just thought, no, I can't. I'll get bullied if I do that.

We were out in Thailand on holiday, me and my two sisters, and my parents sat us down and said... "so we've got some news, Dad's been offered a job back in England, and we're gonna live in Sheffield."

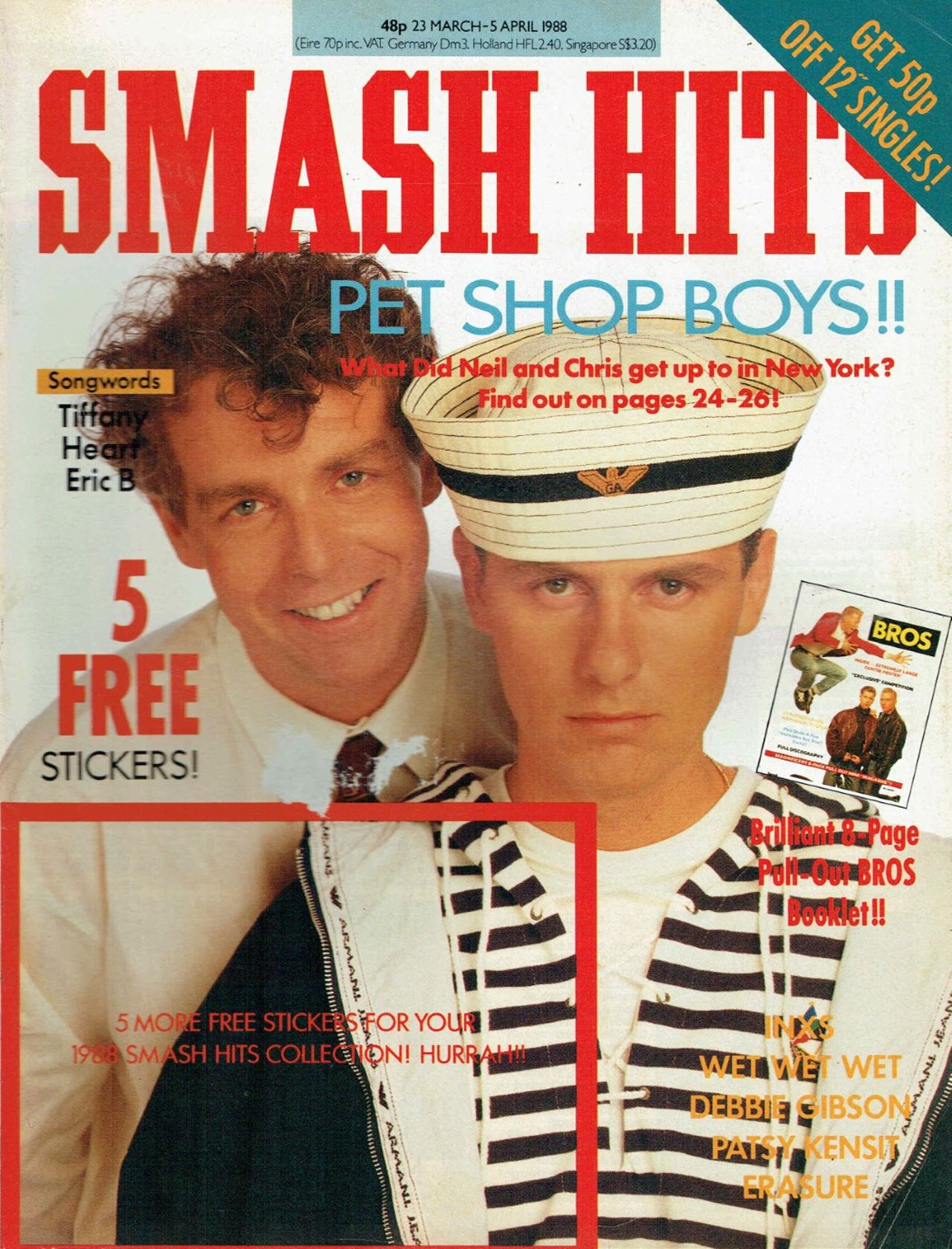

I only knew where Sheffield was because I used to buy [pop magazine] Smash Hits. I’d read about the Pet Shop Boys playing Sheffield Arena. The magazine would arrive in Hong Kong about two or three weeks after publication. So it was always out of date but I loved it.

Above: Sorton's knowledge of Sheffield, where his family moved from Hong Kong, was gleaned from Smash Hits magazine.

It was a massive culture shock coming back [to the UK]. Hong Kong is not a particularly football-y place, but coming to school in England, it felt like if you don't play football, you're in trouble.

I think the concept of reinventing oneself is interesting. I'm a mixture of different things – my Dad's a Yorkshireman, my mom's Indo-Mauritian and Irish, so people have never been able to really place where I'm from. When I came back to England, my school was really white, and I remember racial slurs and being called a queer in a derogatory way. Things are changing now, which is great. It's a conversation that we're all having at the moment.

I did settle down and make friends in the end. When you’re a kid, you end up figuring out how to fit in and survive. I love Sheffield, I still have really good mates there.

I think a lot of kids suffer from feeling different. I did look and sound different to other kids. There is a weird Hong Kong accent a lot of the kids there have that's kind of Australian-y/American-y/English-y. So, in Sheffield, people were like, "are you American? Or Australian? Or Chinese!".

I think Hong Kong gave me a kind of confidence, that diverse cultural perspective you have when you’re living in very different place as a child. I had to adapt to survive and I think that informed how I am as a producer.

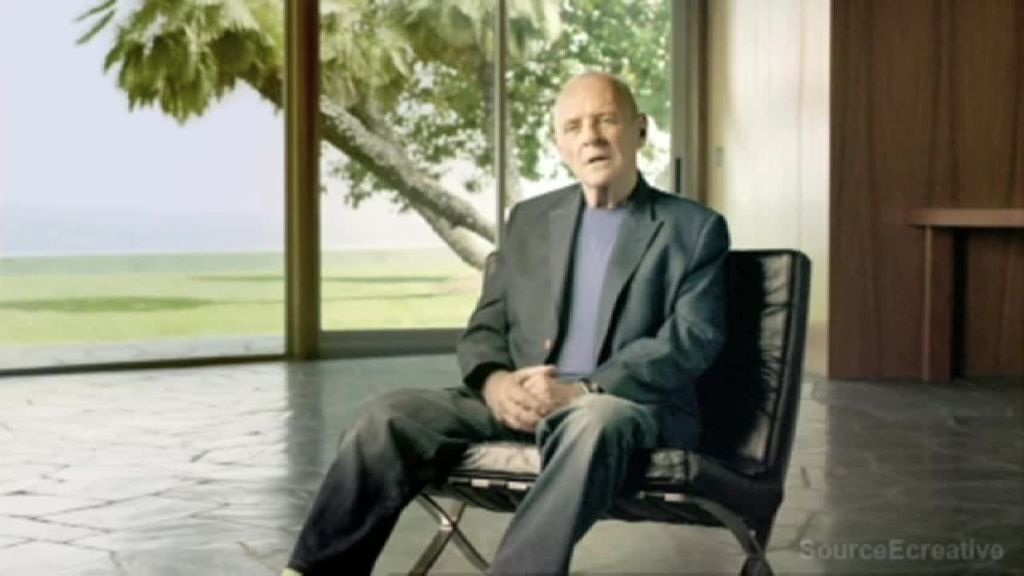

You're talking to a guy who works in a supermarket one minute and Anthony Hopkins the next. What a great job.

Producers are always having to put on different hats. The way you talk to one director/creative/agency producer is totally different to the way you might talk might talk to another one. You have to be a bit of a chameleon, and a politician and a diplomat.

When I started on the job I loved all the different types of interaction; that you'd be talking to the on-screen talent as well as someone you’d street cast for a supermarket ad. One of my first jobs as a producer was a commercial with Anthony Hopkins. We're filming in LA, in this stunning John Lautner-designed house. He came and sat and ate lunch with everybody. He was incredible. After lunch, he was walking in the gardens. I passed him and we started talking. The Hollywood sign was right ahead of us. We had this conversation about why he moved to Hollywood and about his life in film. It was mind blowing. So you're talking to a guy who works in a supermarket one minute and Anthony Hopkins the next. What a great job.

Credits

powered by

- Agency WCRS & Co/London

- Production Company 2AM

- Director John Dower

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency WCRS & Co/London

- Production Company 2AM

- Director John Dower

- Copywriter Lee Boulton

- Art Director Steve Yorke

- CD Leon Jaume

- DP Jan Richter-Friis

- Post Golden Square

- Producer James Sorton

- Talent Anthony Hopkins

Credits

powered by

- Agency WCRS & Co/London

- Production Company 2AM

- Director John Dower

- Copywriter Lee Boulton

- Art Director Steve Yorke

- CD Leon Jaume

- DP Jan Richter-Friis

- Post Golden Square

- Producer James Sorton

- Talent Anthony Hopkins

Above: One of Sorton's first producing jobs was a commercial with Sir Anthony Hopkins.

I studied sociology at Durham University. I’d never been to Durham but I thought, this is one of the best universities, it’ll be good. But I soon realised it wasn't the place for me. I just really stood out. I was put into a Christian college, unbeknownst to me. You had to live [on campus] during that first year, and share rooms. I was this young, gay kid. I thought I can't share a room with someone; it’s too weird. So, I put on my application form, I'm happy to share a room with someone as long as they love the Spice Girls and Kylie. I ended up getting one of the few single rooms.

After my first term I applied to Goldsmiths Collage in London, so I did the rest of my degree there, which was great. I was doing work experience in fashion and in magazines. I knew I wanted to work in a creative environment.

I put on my application form, I'm happy to share a room with someone as long as they love the Spice Girls and Kylie. I ended up getting one of the few single rooms.

I finished my degree and a job came up on reception at Tomboy Films, which was a brilliant place to start out, there are excellent people there. I fell in love with advertising. I liked that it was quick, I have quite a short attention span.

So, I was on reception for two years. Then I got promoted and started getting production experience. Glynis Murray, one of the founders of Tomboy, was amazing, she gave me such an incredible start in my career.

I remember her handing me a budget and saying "just make sure you don't spend more than that". I didn't really have a clue. I'd phone camera and lighting rental places and say, “I don't really know what any of these things are”. But everyone was so generous with their time and wanted to teach me.

Above: Pulse's Bafta-nominated TV series, Gangs of London.

From Tomboy I went to 2AM for six years, which was brilliant, I've always worked at companies that were female run. All my best mates are girls. I did once work at a place where there was quite a bit of toxic masculinity, and I wasn’t happy. In the kitchen there was a tea caddy and instead of Earl Grey, they'd labelled it Earl Gay. Obviously, now, that wouldn't fly.

I joined Pulse 10 years ago. I didn't do a load of freelancing or jump around a million times. I've always quite liked a sense of growing with a place. That's been one of the brilliant things at Pulse, it was this very new company. We were young challengers. People were dismissive of us. They said, "who the fuck are Pulse films"? It's been amazing to see it change and to realise the ambition that we all had.

I didn't do a load of freelancing or jump around a million times. I've always quite liked a sense of growing with a place.

I think we've done well because we always set out to be a multidisciplinary studio, we didn't ever call ourselves a production company. We wanted to work in the areas of commercials, music video, scripted and unscripted. That was always the ambition. And I think there were a lot of people who wanted to do that, but Pulse set their stall out right from the start and invested in each of those areas.

A lot of people want to work in long form but it’s something you've got to really commit to. You can’t just dip in and out of it. Gangs of London, [Bafta-nominated Sky Atlantic drama series] for example, that was a property that [Pulse Co-Founder] Thomas Benski had bought maybe 12 or 13 years ago. It's taken that amount of time for it to come to fruition. It’s not an overnight thing.

Above: Pulse produced Riz Ahmed and Bassam Tariq's feature, Mogul Mowgli, in 2020.

People talk about having a 360° relationship with artists, and I cringe a bit at that term, but it's a dream to work with them across multiple formats. It's been lovely to see that happening with Bassam Tariq and James Marsh. James is an Oscar-winning filmmaker [Man On Wire, The Theory of Everything] and he's now making brilliant commercials with us. He's working with us on a documentary project at the moment as an executive producer.

We made the movie Mogul Mowgli [Bafta-nominated 2020 drama feature by Riz Ahmed and Bassam Tariq ] with Bassam and we're now making commercials with him. He's got this incredible commercial reel that he’s built up in just over a year, since the movie came out.

What's more important; success for the brand or artistic integrity? For me they are symbiotic.

Is there a finite amount of ideas for films and documentaries? I don't think so. Ultimately, they're human stories, and we're never going to run out of those. There are always stories that cut through.

What's more important; success for the brand or artistic integrity? For me they are symbiotic, they have to work concurrently. Otherwise, you've failed as a director or producer. I think there are some brilliant directors who can balance their artistic vision with the message and kind of get the agency and the client to almost bend to their will.

I can't say what my favourite ads that I've worked on are, as I don't want to upset anyone. We’re working on a project with a young director right now and one of our references is Frank Budgen's PlayStation ad Double Life. It's nuts that was made in 1999 and it still gets referenced now, even though the kind of work that we're making maybe more kind of bombastic or visually exciting. But it's such a brilliant commercial; so well written and it looks incredible.

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWALondon/UK

- Production Company Gorgeous

-

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWALondon/UK

- Production Company Gorgeous

- Post Production The Mill London

- Editor John Smith

- Director of Photography Frank Budgen

- Creative Ed Morris

- Creative James Sinclair

- Creative Trevor Beattie

- Director Frank Budgen

- Producer Paul Rothwell

Credits

powered by

- Agency TBWALondon/UK

- Production Company Gorgeous

- Post Production The Mill London

- Editor John Smith

- Director of Photography Frank Budgen

- Creative Ed Morris

- Creative James Sinclair

- Creative Trevor Beattie

- Director Frank Budgen

- Producer Paul Rothwell

Above: Despite being more than 20 years old, Double Life is still used as a reference for new projects.

I think there is a new-found respect for producers. It might be since Covid. When it hit everyone lost their minds for a second, and we all went into war-planning mode.

We knew we had to keep making stuff. And at Pulse, really quickly, we started exploring Zoom, and remote shooting. It sounds weird to say it, but it was a humbling time in that everyone wanted to talk to one another, and help each other, and figure it all out together.

There's actually a strong community among producers in the UK, but it felt much more kind of honest at the start of the pandemic. There's always a little bit of bravado; people say “yeah, we're really busy, we're doing this, we're doing that". But last year was a time where everyone's guard dropped.

There's actually a strong community among producers in the UK, but it felt much more kind of honest at the start of the pandemic.

At that point, I think creatives and agencies were looking to us more than before. Agency partners would call and say, “we're developing this idea but can you have a look at it and just see if you think it's achievable?”. They were involving us more in the writing and logistical side of things, which felt good. I don't know if that's endured, if I'm honest.

If two years ago you'd suggested to directors or agencies that they not turn up to the shoot and just look at it all remotely on a computer, they'd say well that's a crazy thing to do.

Has it permanently changed the way we work? Remote working has its place, but I'm not sure if it's a long-term solution. I heard that an agency CCO said he’d not go on a shoot again, he likes not having the distraction of everything else that's going on around camera. He likes just focussing on what's being shot.

But a lot of what we do... it's not just about the shoot. It's about the relationships you make on the shoot; the dynamics between people.

Above: Sorton produced Goldfish, a Bafta-nominated short film directed by Hector Dockrill.

I love short form. I produced a short film a couple years ago called Goldfish, that was Bafta nominated. It was co-written by one of our directors, Hector Dockrill, and his sister, Laura Dockrill. I'm now working with her on a long-form project, which is amazing as it’s making my brain work in a totally different way. It’s a TV series called What Have I Done?, based on her experience of postpartum psychosis.

Coming to a long-form project as an exec producer, I felt a bit of an outsider. I was talking to Moss Barclay, one of the other producers on it, praising her ability to express her ideas. She said, “you gotta remember, it's just your point of view. It's how something makes you feel". And it's so true. Many people have an insecurity about their opinions. Ultimately what we do is about having a creative point of view.

I talk to a lot of really successful people who mention imposter syndrome; who feel like they’re not worthy of the position they're in.

Often everyone's looking at the director or the creatives and I think producers do have to shout a bit louder to get heard. You have to shout in the right way though.

I talk to a lot of really successful people, especially in this industry, who mention imposter syndrome; who feel like they’re not worthy of the position they're in. I think that feeling sort of keeps you on your toes in a way. If you start believing your own hype, it's sort of over.

I get cross when people are cynical about advertising, because I think it's an incredible business to work in. I think the minute you're cynical about it is the minute you should stop doing it.

)