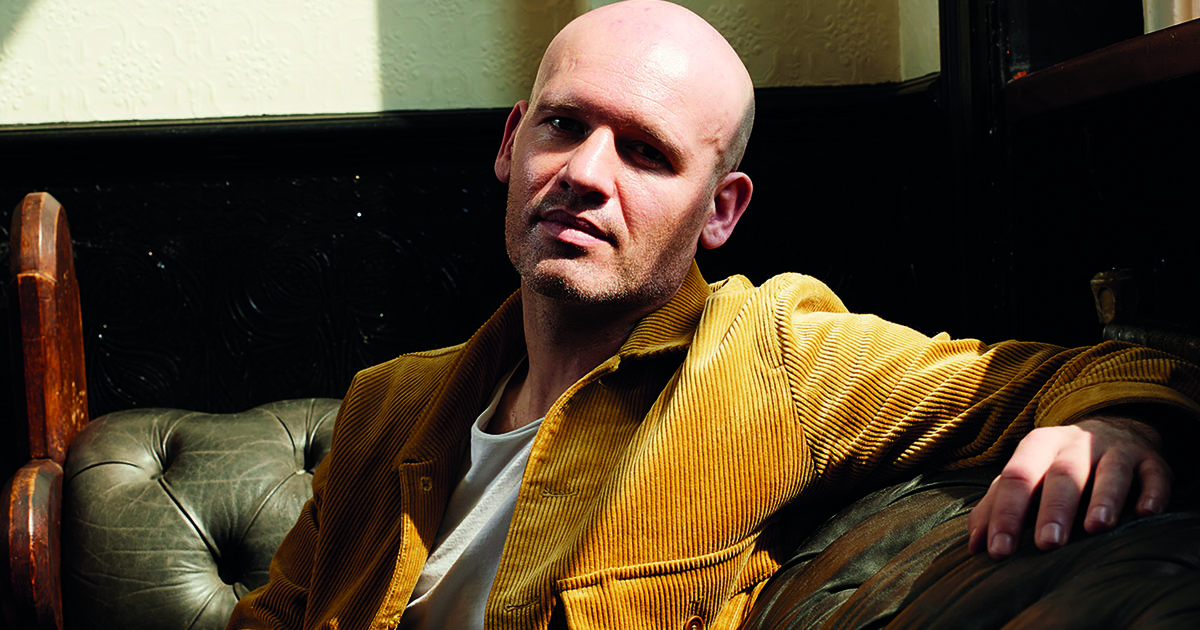

Seb Edwards: Hope & Glory to Rocketman's story

Jamie Madge meets a director whose work always starts with a search for the heart and soul of a film.

It doesn’t take long in a chat with Academy Films director Seb Edwards to spot his passion for film. From discussing his own work to the flicks that inspired him, words like ‘core’ and ‘heart’ and ‘centre’ crop up so frequently, it’s as if his drive to seek the root of what makes a satisfying and compelling story – and his skill in finding it – is innate.

Indeed, the only counterpoint to this passion is the distinct lack of film-fandom on display in his East London flat, save for a solitary movie poster on the wall: Point Blank. The 1967 John Boorman neo-noir crime thriller not only ushered in the American new wave, which Edwards cites as his favourite era – “a golden age when creative freedom brought about some amazing films” – it is also a sly clue to his first experience in movies.

Plucked from a schoolyard as part of an on-street casting, an eight-year-old Edwards found himself, inexplicably, cast in the lead role of Billy in Boorman’s autobiographical feature Hope and Glory. Though this didn’t spark an ongoing interest in performance, it did sow the seed of a love for working on set. “It was an amazing life experience,” he remembers. “I was introduced to a world that I felt quite comfortable in. One I found fascinating. There was this fantastic crew. Just to be part of that family was incredible.”

After completing school and moving on to university to study fine art, his interest in the moving image continued, with Edwards creating “pretentious and abstract” video art. A stint at New York University to study film (on a course-related scholarship) further fed the drive until the hobby became a calling. “I knew I wanted to do something in the art world,” he explains, “but the idea of sitting in a studio with a paintbrush and an easel for the rest of my life was quite scary. I remembered the community and the collaboration involved in filmmaking and started to enjoy the experience of being behind the camera. It was less solitary. I just woke up one day and thought, ‘This all makes sense.’”

A job as a runner at Brave Films [which became Home Corp] proved an entry point into the world of commercial filmmaking and presented him with an idea of the creative opportunities adland could offer. “I never imagined doing commercials,” Edwards comments. “I [remember] saying that to a producer and they pointed out that ads can be very, very creative and a good place to learn and develop as a filmmaker. They got out Jonathan Glazer’s showreel and played it to me and I thought it was the most amazing body of work. It opened my eyes to the potential of going down that route.” Eventually being given the chance to shoot something within Brave, Edwards then found a place at Academy Films – which is Glazer’s production company home – and his career kicked into gear.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Golley Slater/Cardiff

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Golley Slater/Cardiff

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

- Art Director/Writer Phil Hickes

- Art Director/Writer Paul Williams

- Art Director/Writer David Abbott

Credits

powered by

- Agency Golley Slater/Cardiff

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

- Art Director/Writer Phil Hickes

- Art Director/Writer Paul Williams

- Art Director/Writer David Abbott

He had a few commercials under his belt, but it wasn’t until he was working on a couple of PSAs for the British military’s COI (Central Office of Information) in 2008 that everything clicked. “They were, basically, road safety films for the army,” he explains, “based on the fact that a lot of troops come back from war zones with a certain feeling of invincibility. There was this extraordinary statistic saying that the number of people who were getting killed in road accidents was nearly the same as the amount who were dying out in combat. The ideas were very cinematic and the scripts were quite impactful, and I knew what I wanted to do with them straight away. I suddenly felt that I was making something that I understood. It was the first time I really believed in what I was doing.”

“All of the decisions come out instinctively when you have that core idea, so if you don’t believe in it, then you’ve got no compass. You’re lost in the process.”

Picking up two gold Lions at Cannes, the films not only marked something of a career breakthrough for Edwards, but were also a personal connection to his output. Finally making films that were “more like the type of movies I would have watched growing up, with a bit more depth and weight to them”, the army campaign set a template for the kind of work that would bring out the best of his filmmaking abilities – grand cinematic sensibilities with a robust, accessible human message at the core.

Finding this heart, it seems, is the essence of Edwards’ filmmaking process. “What I’ve learnt,” explains Edwards, “is that it’s got to come from a centre that is solid. I work hard in preparation to distil all of the scripts down to their simplest form. I think once you’ve established what the heart and soul of it is, you build out from there.”

“When you’re given the space to follow your instinct, it just works. With Lacoste, I had that freedom. Those shoots are always the most enjoyable.”

Citing the aforementioned freedom of the American new wave in cinema as both an influence and a motivator, it’s when he is given flexibility as a director that his talent really shines. An example is his The Big Leap film for Lacoste – a glorious visual metaphor for the heart-stopping moment before a first kiss. “The Lacoste films were very challenging,” he notes, “but I had creative freedom. When you’re given the space to follow your instinct, it just works. Those shoots are always the most enjoyable.”

“I think I find it hard to fake it,” he continues. “If I’m in a situation where I’m making something I don’t believe in, the end result won’t be great because I wouldn’t really know what to do. All of the decisions come out instinctively when you have that core idea, so if you don’t believe in it, you’ve got no compass. You’re lost in the process.”

Lacoste – The Big Leap

Lacoste – Timeless

Though Edwards, understandably, selects cast and crew who can help realise his ambitions, he’s not tied down to regular collaborators. “I like to work on a project-by-project basis,” he explains. “Up until this stage, I’ve found it quite interesting working with different people, because you always learn something. Everyone comes with a new perspective.”

However, there is one crew member who does have a long-standing relationship with the director, having known him since the day he was born. Sam Rice-Edwards, his older brother, is not only an internationally recognised editor in his own right, but also Edwards’ closest, and most consistent, collaborator. “He understands immediately what I’m trying to do,” Edwards elaborates, “so there are a lot of things that don’t need to be said. He understands the feeling I’m trying to create, because he would naturally go that way himself.”

So the edit suite is free from sibling rivalry? “No way,” he laughs. “He challenges me. Pushes me. It’s not just [a case of] us doing what I want to do or what he wants to do. It can end up in exciting breakthroughs or… us as eight- and ten-year-olds, brawling.”

Credits

powered by

- Agency Adam & Eve -DDB

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

-

-

Unlock full credits and more with a Source + shots membership.

Credits

powered by

- Agency Adam & Eve -DDB

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

- Post Production MPC/London

- Producer Shirley O'Connor

- Production Manager Rachael Donson

- Executive Producer Simon Cooper

- DP Chayse Irvin

- Production Designer Robin Brown

- Editor Sam Rice-Edwards

- Creative Director/Founder Anthony Moore

- VFX Kamen Markov

- VFX Producer Philip Whalley

- CG Supervisor Anthony Bloor

- CG Team Anthony Bloor

- CG Team Jessie Amadio

- CG Team Tom Carrick

- CG Team Charles Downman

- CG Team David Bryan

- 2D Team Kamen Markov

- 2D Team Jack Stone

- 2D Team Kalle Kohlstrom

- 2D Team Bevis Jones

- 2D Team Anthony Bloor

- Chief Creative Officer Richard Brim

- Executive Creative Director Ben Tollett

- Executive Creative Director Mike Sutherland

- Executive Creative Director Antony Nelson

- Producer Sally Pritchett

- Talent Elton John

Credits

powered by

- Agency Adam & Eve -DDB

- Production Company Academy

- Director Seb Edwards

- Post Production MPC/London

- Producer Shirley O'Connor

- Production Manager Rachael Donson

- Executive Producer Simon Cooper

- DP Chayse Irvin

- Production Designer Robin Brown

- Editor Sam Rice-Edwards

- Creative Director/Founder Anthony Moore

- VFX Kamen Markov

- VFX Producer Philip Whalley

- CG Supervisor Anthony Bloor

- CG Team Anthony Bloor

- CG Team Jessie Amadio

- CG Team Tom Carrick

- CG Team Charles Downman

- CG Team David Bryan

- 2D Team Kamen Markov

- 2D Team Jack Stone

- 2D Team Kalle Kohlstrom

- 2D Team Bevis Jones

- 2D Team Anthony Bloor

- Chief Creative Officer Richard Brim

- Executive Creative Director Ben Tollett

- Executive Creative Director Mike Sutherland

- Executive Creative Director Antony Nelson

- Producer Sally Pritchett

- Talent Elton John

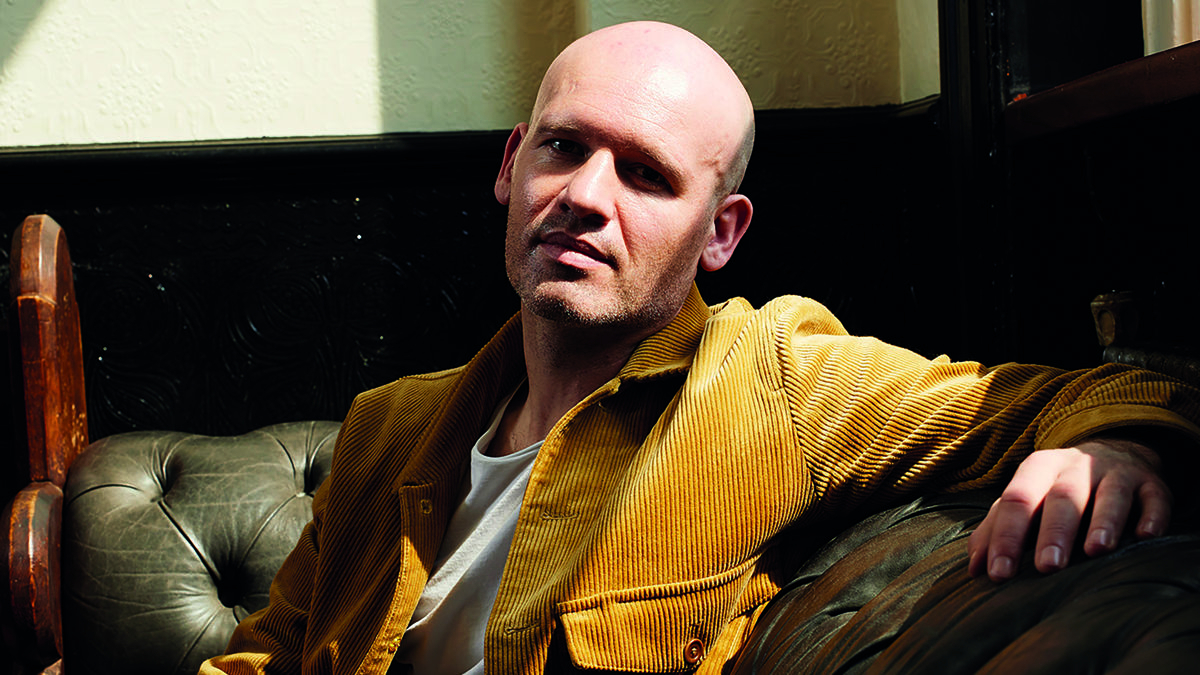

Talk of childhood brings us neatly on to the biggest work in his career to date, The Boy and the Piano – 2018’s entry into the canon of John Lewis Christmas commercials. Undoubtedly the UK’s most-anticipated spot of the year, the brand’s endlessly successful campaigns are now synonymous with the season. So did Edwards feel an extra burden taking this on?

“There’s a certain amount of pressure because you’re facing the expectation of a nation,” he laughs. “It’s become an annual event, so you do want it to be good. But at this stage, I didn’t find it overwhelming.” The key, as with his earlier work, was to find the heart of the story.

If you’re well prepared, it’s amazing how confident you are!

“I had to find something that was at the centre of it, some sort of human truth. In doing the research and reading about Elton John, what emerged was quite an introverted guy who’s created this amazing stage persona. I wanted to make sure that it told a more personal story, which went beyond what we think we know about him – to get inside his head and be given a backstage pass to his life. With something like this, the filmmaking can be quite heightened or crafted, but not style over substance. You’re trying to find something very human or something very truthful at the centre.”

So how was the proposition of directing Elton John to be Elton John? “If you’re well prepared, it’s amazing how confident you are! When you’ve done the work, then whoever you’re talking to, whether it’s an agency, a client, a movie star or famous musician, those conversations are fine. In fact, those conversations are quite enjoyable. As soon as you’re excited and passionate about something then everyone else gets on board with that frame of mind.

“It’s an infectious thing, passion.”

)

+ membership

+ membership